In an emotional ceremony in January, the Cambodian government expressed heartfelt gratitude to a British-Thai woman, Julia Latchford, for what seemed a remarkably generous offer of immense cultural importance. Latchford had agreed to give the southeast Asian country her entire collection of 125 antiquities from Cambodia’s Khmer period — magnificent statues, sculptures, gold and bronze figurines that she had inherited when her father, Douglas Latchford, died last year.

Cambodian Minister of Culture and Fine Arts Phoeurng Sackona described Julia Latchford as “precious and selfless and beautiful,” and said of the historic treasures: “Happiness is not enough to sum up my emotions... It’s a magical feeling to know they are coming back.”

Behind the ceremonial smiles lay a shameful reality: During Cambodia’s decades of turmoil, its astonishing cultural heritage, sacred antiquities crafted as long ago as the ninth century, were ruthlessly plundered and sold around the world.

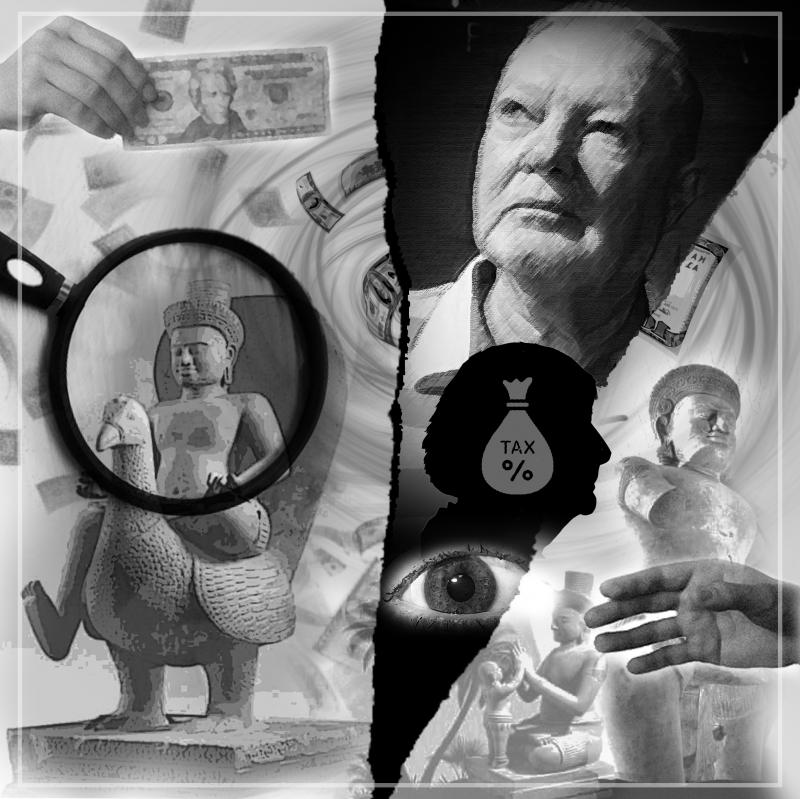

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

Douglas Latchford, who lorded it over the Cambodian cultural scene for decades and was hailed as an expert and benefactor, had been accused before he died of being a prolific trader in looted antiquities, and charged with criminal offenses.

From his base in Bangkok, Douglas Latchford bought sculptures he is alleged to have known were originally ransacked from Cambodia’s ancient sites by organized criminals, then made millions selling them through prestige dealers and auction houses in London, New York and elsewhere. Glories of Khmer heritage ended up in some great museums and wealthy private homes, and Cambodia, assisted by the US government, is seeking their return.

Youk Chhang, the director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, which maintains records of the “killing fields” genocide perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge regime from 1975 to 1979, said the return of its heritage is key to repairing the country.

“Cambodia is still in search of her identity, which has been eradicated by French colonialism, war and genocide, for many decades,” he said. “Cultural and religious heritage is a form of her identity and all the broken pieces must be put back in place.”

Douglas Latchford’s decades-long career illuminates huge questions about the restitution of sacred heritage looted from many countries for triumphant display in the West. The “Pandora Papers,” which were leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), expose another part of his empire: the use of trusts and offshore tax havens to pass his assets, including the Khmer antiquities, to his daughter to avoid them becoming liable to UK inheritance tax.

Papers held by an offshore services provider show how Douglas Latchford formed two trusts in Jersey, both named after Hindu gods: the Skanda Trust in 2011 and the Siva Trust in 2012. Julia Latchford and other members of the family were beneficiaries, and she was a trustee of the Skanda Trust. Another trustee was a company, Skanda Holdings, registered in the British Virgin Islands, with Douglas Latchford, and Julia Latchford’s husband, Simon Copleston, its directors.

The papers reveal that the Skanda Trust had accounts in other offshore tax havens, including with Rathbones, a wealth management firm in Jersey, where considerable amounts of money were held and invested.

In 2011, almost simultaneously with the formation of the Skanda Trust, Latchford credited it as the owner of 80 Cambodian antiquities in a glossy book he published, Khmer Bronzes. No details were given for the trust, nor was it explained that the new owner of the antiquities was a structure formed for the benefit of Douglas Latchford and his family. Khmer Bronzes was the third book featuring Cambodian treasures published by Douglas Latchford, following Adoration and Glory in 2004, and in 2008, Khmer Gold.

In 2003, the US and Cambodian governments signed a landmark agreement committing to tracing and pursuing the return of all looted heritage, an effort led by the US Homeland Security Investigations (HSI). An antiquities trafficking unit was formed in New York in 2017, dedicated to investigating stolen treasures.

The first US legal action that identified Douglas Latchford as a looter, and stunned the dealing world, followed the halting in March 2011 of a proposed sale in New York by Sotheby’s of a 10th-century Cambodian sandstone sculpture, Duryodhana bondissant, alleged to have been stolen from Prasat Chen, a temple at the 10th-century Khmer capital, Koh Ker.

Douglas Latchford was alleged in the legal action to have bought the Duryodhana bondissant in 1972 knowing it was looted, consigned it to a London auction house, Spink & Son, then conspired with Spink’s representatives to “fraudulently obtain export licenses.”

He was rocked again in 2016 when Nancy Wiener, a celebrated New York gallery owner, was indicted, charged with possessing stolen property. Two 10th-century pieces supplied by Douglas Latchford featured in the charges: a statue of the Hindu god Shiva valued at US$578,500 and a bronze Buddha sitting on a throne of Naga that Douglas Latchford sold Wiener for US$500,000.

Wiener on Wednesday last week pleaded guilty, admitting buying those figures from Douglas Latchford knowing they had been looted, then selling them with false provenance.

The Naga Buddha “appeared to have been struck by an agricultural tool,” a sign of “illegal excavation,” she said, but nevertheless she put it up for sale for US$1.5 million.

A photograph of the Naga Buddha, attributed to the Skanda Trust, was featured in Khmer Bronzes. The indictment alleged that such books were themselves part of falsifying antiquities’ provenance, presenting them as respectable.

“Publishing a photograph of a looted antiquity is a common laundering practice,” HSI special agent Brenton Easter said.

The cover of Latchford’s 2004 book, Adoration and Glory, featured a picture of a Khmer sculpture, Shiva and his son Skanda, the god of war. As recently as July, US authorities alleged the sculpture had been looted from the Prasat Krachap temple complex in Koh Ker, carried away by a gang of looters on an oxcart in September 1997 with 12 more significant statues.

The Shiva and Skanda sculpture is one of the first five pieces Julia Latchford has returned to Cambodia. The US action is seeking to seize another of those masterpieces, Skanda on a Peacock, from its current, unnamed owner. Douglas Latchford is alleged to have sold it in April 2000 for US$1.5 million.

Interviewed in 2012 after the clouds had begun to shadow him, Douglas Latchford presented himself as a savior, saying Cambodian antiquities were in “better hands” and would otherwise have been destroyed during years of violence and occupation by Vietnam through the 1980s.

Douglas Latchford made a tremendous amount of money from his trade and continued to sell until as late as 2018, according to evidence obtained by the ICIJ.

In November 2019, Douglas Latchford was charged in New York. The 25-page indictment included charges of selling stolen property, smuggling, falsifying documents, wire fraud and other offences relating to buying and selling antiquities looted from Koh Ker. He was terminally ill by then and incapacitated. He did not have the chance to defend himself against the charges, as he died in August last year.

Although the Cambodian government responded magnanimously to Julia Latchford’s promise of returning everything she had, she acknowledges that law enforcement authorities continue to investigate her father’s estate, which she inherited, for proceeds of crime.

In 2016, following the Wiener indictment, Douglas Latchford’s investments, said to include the Rathbones account, are understood to have been subject to a suspicious activity report in Jersey, a format that enables suspected money laundering to be reported to relevant authorities.

Julia Latchford, 50, said she and Copleston were not personally subject to any investigation, and had not been involved in the sales of antiquities while they were part of the Skanda and Siva trust structure.

During the time that the “inheritance trust structure held the collection of Cambodian artifacts,” which she said ended in 2016, her father had given her “credible” assurance that the allegations against him were false, she said.

She was also reassured by the “close relationship” Douglas Latchford still had then with museums and the Cambodian authorities and that major European auction houses continued to sell Khmer antiquities.

“I now know from recent research into his affairs, and becoming aware of information not available to us at the time [including the findings of law enforcement bodies] that in general and in particular cases, he lied to me, and concealed certain actions from me,” she said.

She began to hold independent discussions with the Cambodian government from 2017, she said, and her promise to return all the antiquities is understood to have been part of a formal agreement she signed with Phnom Penh shortly after her father died.

She has agreed also to hand over his full documentation, said to include an inventory of his sales and extensive wider evidence of the global trade in Khmer antiquities.

Negotiations with her were led by two US lawyers, Bradley Gordon and Steven Heimberg, representing the Cambodian Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts.

Their sole focus is the return of the heritage, including all of about 600 pieces featured in Latchford’s three books, Gordon said.

“Our approach is that all of the sacred statues and other antiquities from the [ninth to 15th-century] Angkor and pre-Angkor period that have been taken out from Cambodia, particularly since 1970, have been removed illegally,” Gordon said. “The burden is on the person with possession to show they have proper permits and provenance. Very few people, if any, when asked, will be able to come up with proper permits and provenance.”

Julia Latchford said of the continuing investigation into her father’s money: “I am aware of and am voluntarily cooperating with the authorities on the investigations with respect to my father’s estate and any proceeds of crime and am committed to their resolution.”

Her representatives have emphasized that Douglas Latchford made substantial money independently of trading antiquities, in pharmaceutical companies across southeast Asia and property development.

Julia Latchford has also said she does not regard all his antiquities trading to have been illegal, suggesting she does not intend to return all the money from his sales of Khmer antiquities.

“We understood [and still understand] his collection to comprise many objects with strong provenance,” she said.

Tracing where Cambodia’s cultural heritage ended up is dizzying detective work, spanning continents and taking in different museums, dealers and a still unknown number of wealthy people who bought pieces.

People unfamiliar with the dirty trade in sacred antiquities might assume that Douglas Latchford’s 2019 indictment rang an alarm worldwide, and every organization and person holding Khmer treasures that might have come from him will have inspected their provenance. In general, that has not happened.

Tess Davis, the executive director of the Washington-based Antiquities Coalition, who has extensively researched Douglas Latchford and Cambodian looting networks, said that with a few exceptions, the response of museums worldwide has been “deafening silence.”

Spink & Son was taken over by Christie’s in 1993. A Christie’s spokesperson said they could not discuss Spink’s past sales of Khmer relics now held in many prominent museums, and whether they were supplied by Douglas Latchford.

Asked if they were in contact with the relevant authorities, the spokesperson said: “Christie’s is actively engaged in supporting the repatriation of illegally exported cultural property and is in contact with governments and law enforcement agencies as appropriate. We cannot provide specific details.”

The British Museum has five pieces Douglas Latchford donated — from Thailand, not Cambodia, and has received “no official request” for their return, a spokesperson said.

Of 46 Khmer sculptures, none came from Douglas Latchford, all but two were certainly removed from Cambodia before 1970, and the museum “has not received an approach from the Cambodian government” concerning them, the spokesperson said.

Still, the detective work continues, the slow process of reuniting a country with the treasures of its past that have been ruthlessly looted, transported, traded and stashed away offshore.

The image was oddly quiet. No speeches, no flags, no dramatic announcements — just a Chinese cargo ship cutting through arctic ice and arriving in Britain in October. The Istanbul Bridge completed a journey that once existed only in theory, shaving weeks off traditional shipping routes. On paper, it was a story about efficiency. In strategic terms, it was about timing. Much like politics, arriving early matters. Especially when the route, the rules and the traffic are still undefined. For years, global politics has trained us to watch the loud moments: warships in the Taiwan Strait, sanctions announced at news conferences, leaders trading

The saga of Sarah Dzafce, the disgraced former Miss Finland, is far more significant than a mere beauty pageant controversy. It serves as a potent and painful contemporary lesson in global cultural ethics and the absolute necessity of racial respect. Her public career was instantly pulverized not by a lapse in judgement, but by a deliberate act of racial hostility, the flames of which swiftly encircled the globe. The offensive action was simple, yet profoundly provocative: a 15-second video in which Dzafce performed the infamous “slanted eyes” gesture — a crude, historically loaded caricature of East Asian features used in Western

Is a new foreign partner for Taiwan emerging in the Middle East? Last week, Taiwanese media reported that Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) secretly visited Israel, a country with whom Taiwan has long shared unofficial relations but which has approached those relations cautiously. In the wake of China’s implicit but clear support for Hamas and Iran in the wake of the October 2023 assault on Israel, Jerusalem’s calculus may be changing. Both small countries facing literal existential threats, Israel and Taiwan have much to gain from closer ties. In his recent op-ed for the Washington Post, President William

A stabbing attack inside and near two busy Taipei MRT stations on Friday evening shocked the nation and made headlines in many foreign and local news media, as such indiscriminate attacks are rare in Taiwan. Four people died, including the 27-year-old suspect, and 11 people sustained injuries. At Taipei Main Station, the suspect threw smoke grenades near two exits and fatally stabbed one person who tried to stop him. He later made his way to Eslite Spectrum Nanxi department store near Zhongshan MRT Station, where he threw more smoke grenades and fatally stabbed a person on a scooter by the roadside.