A short bureaucratic note from a brutally degraded microstate in the South Pacific region to a little-known institution in the Caribbean is about to change the world. Few people are aware of its potential consequences, but the effects are certain to be far-reaching. The only question is whether that change will be to the detriment of the global environment or the benefit of international governance.

In late June, the island republic of Nauru informed the International Seabed Authority (ISA), based in the Jamaican capital of Kingston, of its intention to start mining the seabed within two years via a subsidiary of a Canadian firm, The Metals Co (TMC), formerly known as DeepGreen Metals. Innocuous as it sounds, this note was a starting gun for a resource race on the planet’s last vast frontier: the abyssal plains that stretch between continental shelves deep below the oceans.

In the three months since it was fired, the sound of that shot has reverberated through government offices, conservation movements and academic institutions, and is now starting to reach a wider public, who are asking how the fate of the greatest of global commons can be decided by a sponsorship deal between a tiny island nation and a multinational mining corporation.

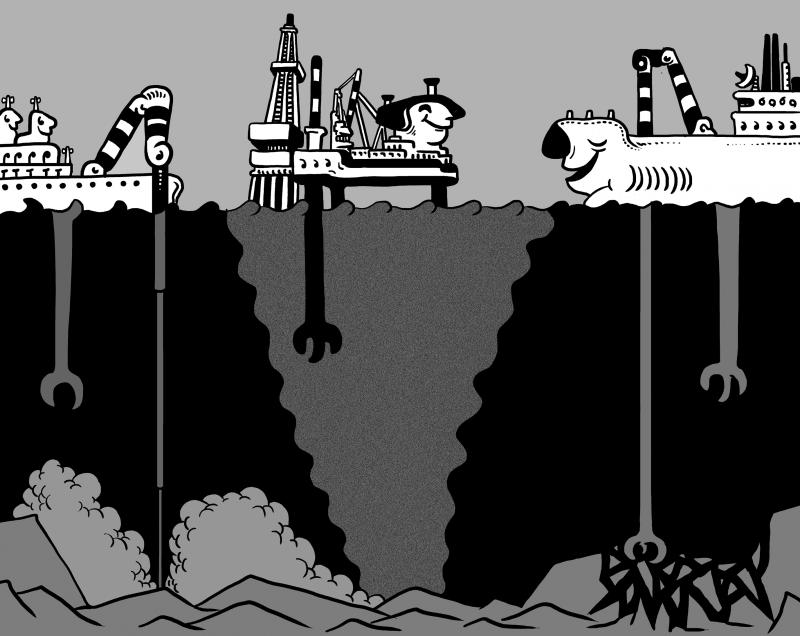

Illustration: Mountain People

The risks are enormous. Oversight is almost impossible. Regulators admit that humanity knows more about deep space than the deep ocean. The technology is unproven. Scientists are not even sure what lives in those profound ecosystems. State governments have yet to agree on a rulebook on how deep oceans can be exploited. No national ballot has ever included a vote on excavating the seabed.

Conservationists, including David Attenborough and Chris Packham, say that it is reckless to go ahead with so much uncertainty and such potential devastation ahead.

Louisa Casson, an oceans campaigner at Greenpeace International, said that the two-year deadline is “really dangerous.”

Given the potential risks of fisheries disturbance, water contamination, sound pollution and habitat destruction for dumbo octopuses, sea pangolins and other species, no new licenses should be approved, she said.

“This is now a test of governments who claim to want to protect the oceans,” Casson said. “They simply cannot allow these reckless companies to rush headlong into a race to the bottom, where little-known ecosystems will be ploughed up for profit, and the risks and liabilities will be pushed on to small island nations. We need an urgent deep-sea mining moratorium to protect the oceans.”

Mining companies also insist on urgency — to start exploration.

They say that the minerals — copper, cobalt, nickel and magnesium — are essential for a green transition.

If the world wants to decarbonize and reach net-zero emissions by 2050, we must start extracting the resources for vehicle batteries and wind turbines soon, they say.

They already have exploration permits for an expanse of international seabed as large as France and Germany combined, an area that is likely to expand rapidly.

All they need now is a set of internationally agreed operating rules.

The rulebook is being drawn up by the ISA, set up in 1994 by the UN to oversee sustainable seabed exploration for the benefit of all humanity.

However, progress is slower than mining companies and their investors would like.

That is why Nauru’s action is pivotal. By triggering the “two-year rule,” Nauru has in effect given regulators two years to finish the rulebook.

At that point, TMC’s subsidiary Nauru Ocean Resources Inc (NORI), intends to apply for approval to begin mining in the Clarion-Clipperton zone, an expanse of the North Pacific between Hawaii and Mexico.

DEEP SEA WONDERS

The deep ocean is the least known environment on Earth, a realm that still inspires awe and wonder. By one estimate, 90 percent of the species that researchers collect there are new to science, including the pale “ghost” octopus that lays its eggs on sponge stalks anchored to manganese nodules or the single-celled, tennis-ball sized xenophyophores.

In the midnight, hadal and abyssal zones, fish and other creatures must make their own light. Biolumescent loosejaw and humpback blackdevils, a type of anglerfish, have evolved with in-built lanterns to seek out and draw in their prey.

First-time human visitors often go expecting darkness and return filled with wonder at the undersea displays of living fireworks.

Marine biologists believe there might be more bioluminescent creatures in the deep sea than there are species on land.

There is also thought to be a greater wealth of minerals such as copper, nickel, cobalt and rare earth elements such as yttrium, as well as substantial veins of gold, silver and platinum.

Most are found near hydrothermal vents or in rock concretions known as olymetallic nodules that can be as big as a fist or as small as a fleck of skin. The challenge is gouging them out and lifting them to the surface.

When the first attempts were made to harvest nodules in the mid-1970s, the chief executive in charge of the operation exasperatedly described the task as like “standing on the top of the Empire State Building, trying to pick up small stones on the sidewalk using a long straw, at night.”

Today’s technology has moved on, but scientists and conservationists doubt that it is ready and the environmental risks are fully understood. They would like more time.

Nauru and TMC have given them less. The countdown clock now has 21 months left, and counting.

History does not offer much encouragement to the denizens of the deep that the issue would be resolved in their favor.

LONG-TERM FOCUS

Mining has provided the building blocks of civilization. Without ore, humankind could not have had the iron age, the bronze age and certainly not the great cultures of ancient China, Nubia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, the Aztecs or Mayans.

In modern times, particularly the great post-World War II acceleration of the past 70 years, more has probably been gouged from the Earth than in all of previous human history combined.

The materials for a built and manufactured environment are extracted at the expense of natural beauty, resilience and stability. For most of human history, this was considered a fair trade-off.

The costs — cleared forests, scarred landscapes, polluted water, air filled with dust, carcinogens and greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere — were either unknown or deemed small compared with the gains. They rarely appeared on corporate or national balance sheets. Miners extracted oil, gas, coal, iron, gold, copper, lithium and other minerals, while leaving other species, remote communities and future generations to pay the price.

Mining has often proved a trade based on imported resources and exported risk.

In the past few decades, this trade-off has come into question as scientific knowledge of the consequences has advanced. Environmental concerns have prompted calls for stricter regulation.

However, oversight, if it exists at all, is often shaped by those who stand to benefit in the short term rather than those left to clean up the mess.

Meanwhile, mines are moving further from power centers, which means less likelihood of “not-in-my-backyard” protests, media coverage, challenges by conservationists or legal redress.

Most of today’s mega-mines are in remote regions: the Carajas iron ore complex and the Paragominas bauxite mine in the state of Para in northern Brazil; the Oyu Tolgoi copper mine in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert; the Bingham Canyon copper mine in Utah’s Oquirrh Mountains; the Chuquicamata copper mine in Chile’s Atacama Desert; the Mirny mine in eastern Russia; or the many offshore oil and gas wells in the Gulf of Mexico, the North Sea, the Caribbean and elsewhere.

If mining in the deep ocean is technologically challenging and expensive, then independent oversight is even tougher: Beyond all national jurisdictions, too expensive for environmental organizations to reach, too inaccessible for all but invited journalists to visit, and totally free of people so no chance of hold-ups by protesters. Fish, crustaceans and microbes might suffer, but they cannot complain.

NEW ‘ROBBER BARON ERA’

Just like almost every other mining project in history, TMC and other mining companies promise to maintain the highest environmental standards and to operate within guidelines laid out by regulatory bodies — and just like almost every other mining project in history, it is in their interest to exert pressure on those same regulatory bodies to ensure projects go ahead quickly with environmental standards that do not sink their bottom line.

Payal Sampat, mining program director at the Earthworks environmental charity, said the rushed approach to deep-sea mining was reminiscent of the wild-west prospectors of the 19th century.

“This really is a throwback to the early robber baron era. Our global heritage is being decided in small backroom discussions. Most people are completely unaware that this enormous planet-changing decision is being made. It is very nontransparent,” Sampat said, adding that the mining industry had never been properly regulated.

Today’s mega-pits are so big that they can be seen from space, but they are governed by laws drawn up 150 years ago in the era of picks and shovels, she said.

“Deep-sea mining really represents a continuation of that destructive extractivist mindset. It is all about looking at the next frontier rather than using the resources we already have much better,” she said.

The wasteland Nauru might provide a salutary reminder of the destructive spiral that follows when an ecosystem is sucked dry.

Once described as a Pacific idyll, the island’s topsoil was stripped of phosphate first by the British, then the Germans, then New Zealanders and Australians.

They wanted the deposits to fertilize gardens and farmland in their own countries, and promised to restore the landscape and fully compensate those affected by environmental damage.

By the time of independence in 1968, enough phosphate was left to briefly make the country’s 12,000 inhabitants the second-richest people on Earth. As phosphate prices rose from US$10 a tonne to more than US$65 in the 1970s, GDP per capita topped US$50,000, at the time second only to Saudi Arabia.

However, within two decades, the resource was virtually exhausted, leaving an inland moonscape of gnarled, spiky rock and an economy in tatters.

Restitution funds were supposed to rehabilitate 400 hectares, but they have been frittered away in the past 25 years with barely six hectares recovered.

The gutting of the topsoil has caused unforeseen problems to the local climate, vegetation and society. Loss of vegetation has prevented rain clouds from forming over the island and led to more droughts. Several endemic plant species are now endangered and food production has been affected. Locals have turned from healthy local produce, such as coconuts, to fatty and salty tinned goods, resulting in one of the highest levels of obesity, heart disease and diabetes in the world.

As one former Nauruan minister of finance put it: “Nauru was once a tropical paradise, a rainforest hung with fruits and flowers, vines and orchids. Now, thanks to human avarice and short-sightedness, our island is mostly a wasteland.”

The 12,000 inhabitants have resisted repeated attempts to relocate them to an island off the Australian state of Queensland and looked for new ways to make a living.

After the economy collapsed, the desperate Nauruan government turned to offshore banking, but with customers that included the Russian mafia and al-Qaeda, the US Treasury blacklisted the island as a center of money laundering and corruption.

After that failure, the microstate rented itself out to Australia as a detention center for asylum seekers, a business that now provides more than half of state revenue. When that declined, Nauru began to eye up the surrounding seabed by teaming up with TMC, which is paying tens of millions of US dollars a year in royalties for its fully owned NORI subsidiary.

OVERSIGHT CHALLENGES

At the ISA, Nauru is supposed to be a sponsor nation for TMC. In reality, the island acts more like a client state for the corporation, and a company executive can behave as its spokesperson. In 2019, then-DeepGreen chairman Gerard Barron was listed as a member of the Nauru delegation and spoke from the island’s seat in the plenary meeting.

Little wonder then that eyebrows were raised when the tiny nation, which constitutes just 0.00016 percent of the world’s population, took the initiative to open up the seabed. Few observers doubt that this was done at the behest of TMC.

Deep Sea Conservation Coalition cofounder Matthew Gianni said: “This is all about money — money for DeepGreen and its shareholders and money for Nauru — and the fear that if DeepGreen doesn’t get a licence soon, investors will walk away from the company, and both DeepGreen and Nauru will lose out on any revenue.”

The case showed the need to shake up international governance, he said.

“The ISA’s decisionmaking process is seriously flawed and needs to be fixed,” Gianni said

In lieu of comment, TMC referred questions to three external experts that it said specialized in deep-sea ecosystems and plume dynamics.

TMC is among a cluster of mining companies that argue that seabed minerals are essential if the world is to make the transition from fossil fuels to renewables.

Barron, TMC chief executive officer and chairman, is fond of stating that a single 75 kilowatts electric vehicle battery requires 56kg of nickel and 7kg each of manganese and cobalt, plus 85kg of copper for the vehicle’s wiring.

To convert the world’s more than 1 billion vehicles with combustion engines into electric ones would require far more metal than is currently produced on land, he said.

Tapping seabed resources would still not close the supply gap, but could accelerate the transition, reduce mining emissions and provide revenue for poorer countries, he said.

As a sign of TMC’s commitment to the environment, he said that the company would halt production after the world has enough minerals for 2 billion batteries, because that would be enough to allow full recycling.

However, many battery-makers and industrial users are lining up with the conservationists rather than the miners.

In April, BMW, Volvo, Google and Samsung joined a WWF call for a moratorium on seabed mining.

Scientists and campaigners say that TMC is creating a false sense of urgency about the need for deep-sea minerals.

They say existing mineral supplies are sufficient for the coming 10 years and after that much of the demand could be met by fast-improving recycling technology.

Others are skeptical about the promise of a 2 billion battery cap.

Lisa Levin, a professor of biological oceanography at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said: “Once you start up a new industry it won’t just be DeepGreen, it will be multiple countries. It will be very hard to stop. Mining needs to continue for 20 or 30 years to recoup investment. It’s not something you put back in the box.”

Two weeks ago, Malaysian actress Michelle Yeoh (楊紫瓊) raised hackles in Taiwan by posting to her 2.6 million Instagram followers that she was visiting “Taipei, China.” Yeoh’s post continues a long-standing trend of Chinese propaganda that spreads disinformation about Taiwan’s political status and geography, aimed at deceiving the world into supporting its illegitimate claims to Taiwan, which is not and has never been part of China. Taiwan must respond to this blatant act of cognitive warfare. Failure to respond merely cedes ground to China to continue its efforts to conquer Taiwan in the global consciousness to justify an invasion. Taiwan’s government

Earlier signs suggest that US President Donald Trump’s policy on Taiwan is set to move in a more resolute direction, as his administration begins to take a tougher approach toward America’s main challenger at the global level, China. Despite its deepening economic woes, China continues to flex its muscles, including conducting provocative military drills off Taiwan, Australia and Vietnam recently. A recent Trump-signed memorandum on America’s investment policy was more about the China threat than about anything else. Singling out the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a foreign adversary directing investments in American companies to obtain cutting-edge technologies, it said

The recent termination of Tibetan-language broadcasts by Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) is a significant setback for Tibetans both in Tibet and across the global diaspora. The broadcasts have long served as a vital lifeline, providing uncensored news, cultural preservation and a sense of connection for a community often isolated by geopolitical realities. For Tibetans living under Chinese rule, access to independent information is severely restricted. The Chinese government tightly controls media and censors content that challenges its narrative. VOA and RFA broadcasts have been among the few sources of uncensored news available to Tibetans, offering insights

“If you do not work in semiconductors, you are nothing in this country.” That is what an 18-year-old told me after my speech at the Kaohsiung International Youth Forum. It was a heartbreaking comment — one that highlights how Taiwan ignores the potential of the creative industry and the soft power that it generates. We all know what an Asian nation can achieve in that field. Japan led the way decades ago. South Korea followed with the enormous success of “hallyu” — also known as the Korean wave, referring to the global rise and spread of South Korean culture. Now Thailand