Protests have intensified outside property giant Evergrande Group’s offices across China, as the developer falls farther behind on promises to more than 70,000 investors. Construction of unfinished properties with enough floor space to cover three-fourths of Manhattan has ground to a halt, leaving more than 1 million homebuyers in limbo.

Fire sales pummel a shaky real-estate market, squeezing other developers and rippling through a supply chain that accounts for more than one-quarter of Chinese economic output.

People, weary of the COVID-19 pandemic, retrench further and the risk of popular discontent rises during a politically sensitive transition period for Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平).

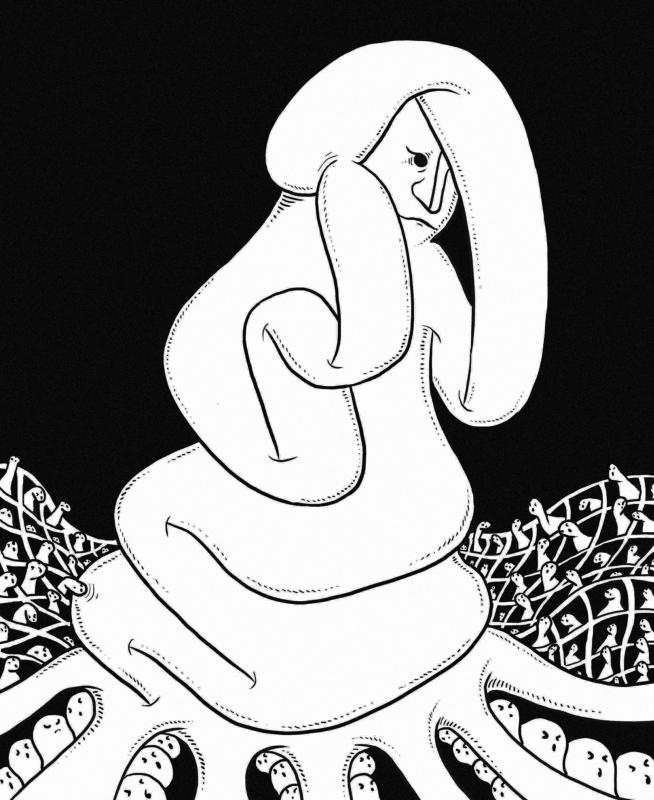

Illustration: Mountain People

Credit-market stress spreads from lower-rated property companies to stronger peers and banks. Global investors who bought US$527 billion of Chinese stocks and bonds in the 15 months through June are selling.

While it is impossible to know for sure what would happen if Beijing allowed Evergrande’s downward spiral to continue unabated, China watchers are gaming out worst-case scenarios as they contemplate how much pain the Chinese Communist Party is willing to tolerate. Pressure to intervene is growing as signs of financial contagion increase.

“As a systemically important developer, an Evergrande bankruptcy would cause problems for the entire property sector,” said Shen Meng (沈萌), director of Chanson & Co, a Beijing-based boutique investment bank. “Debt recovery efforts by creditors would lead to fire sales of assets and hit housing prices. Profit margins across the supply chain would be squeezed. It would also lead to panic-selling in capital markets.”

For now, Shen and nearly all of the other bankers, analysts and investors interviewed for this story say that Beijing is in no mood for a Lehman Brothers moment. Rather than allow a chaotic collapse into bankruptcy, they predict that regulators will engineer a restructuring of Evergrande’s US$300 billion pile of liabilities, keeping systemic risk to a minimum.

Markets seem to agree: China’s Shanghai Composite Index is less than 3 percent from a six-year high, while the yuan is trading near a three-month high against the US dollar.

Yet a benign outcome is far from assured. Beijing’s bungled stock-market rescue in 2015 showed how difficult it can be for policymakers to control financial outcomes, even in a system where the government runs most of the banks and can exert outsized pressure on creditors, suppliers and other parties.

Contagion risk was on full display on Sept. 9. Chinese junk-bond yields jumped to an 18-month high and shares of real-estate companies plunged after Evergrande had its credit rating downgraded and requested a trading halt in its onshore bonds.

Some banks in China appear to be hoarding yuan at the highest cost in almost four years, a sign that they might be preparing for what a Mizuho Financial Group strategist called a “liquidity squeeze in crisis mode.” Where Xi will ultimately draw the line remains a mystery. While China’s State Administration for Market Regulation has urged billionaire Evergrande founder Xu Jiayin (許家印), or Hui Ka Yan in Cantonese, to solve his company’s debt problems, authorities have yet to spell out whether the government would allow a major debt restructuring or bankruptcy.

Even senior officials at state-owned banks have privately said that they are still waiting for guidance on a long-term solution from top leaders in Beijing.

Evergrande’s main banks had been told by the Chinese Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development that the developer could not make interest payments due on Monday, people familiar with the matter said.

The Chinese government is not averse to taking over companies from the private sector if needed. It seized Baoshang Bank in 2019 and assumed control of HNA Group, the once-sprawling conglomerate, early last year after the pandemic decimated the company’s main travel business. Court-led restructurings have also become more common in the past few years, with more than 700 being completed last year.

The Evergrande endgame might largely depend on how Xi decides to balance his goals of maintaining social and financial stability against his multi-year campaign to reduce moral hazard. The timing is particularly tricky as China juggles an economic slowdown, a sweeping crackdown on the private sector and rising tensions with Washington — all in the run-up to a once-in-five-year leadership reshuffle next year, at which Xi is set to extend his indefinite rule.

“The government has to be very, very careful in balancing support for Evergrande,” said Yu Yong (於勇), a former regulator with the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission and now chief risk officer at China Agriculture Reinsurance Fund.

“Property is the biggest bubble that everyone has been talking about in China,” Yu told Everbright Sun Hung Kai analyst Jonas Short in a recent podcast. “So if anything happens, this could clearly cause systematic risk to the whole China economy.” Here are some of the factors that may sway Chinese leaders:

SOCIAL UNREST

Maintaining social order has always been paramount for the Chinese Communist Party, which has little tolerance for protests of any kind. In Guangzhou, homebuyers earlier this month surrounded a local housing bureau to demand that Evergrande restart stalled construction. Last week, disgruntled retail investors gathered at the company’s Shenzhen headquarters, and unconfirmed videos of protests against the developer in other parts of China have been shared widely online.

Evergrande had 1.3 trillion yuan (US$201.04 billion at the current exchange rate) in presale liabilities at the end of June, equivalent to about 1.4 million individual properties that it has committed to complete, a Capital Economics report said.

“If Evergrande had to dump its inventory onto the market, it would drag down property prices substantially,” Bocom International chief strategist Hao Hong (洪灝) said.

Without a social safety net and with limited places to put their money, Chinese savers have for years been encouraged to buy homes, whose prices were only ever supposed to go up. Today, real estate accounts for 40 percent of household assets and buying a house (or two) is a cultural touchstone. While housing affordability has become a hot topic in the West, many Chinese are more likely to protest falling home prices than spiking ones.

“Given that the bulk of people’s wealth is already in property, even a 10 percent correction would be a serious knock to many people,” said Fraser Howie, an independent analyst and coauthor of books on Chinese finance who has been following the country’s corporate sector for decades. “It would certainly knock their hopes and dreams and expectations about what property is.”

Another potential flashpoint is whether Evergrande can repay high-yield wealth management products that it sold to thousands of retail investors, including many of its own employees.

About 40 billion yuan of the wealth management products are due to be repaid, reported Caixin, a Chinese financial news service.

Evergrande is trying to free up cash by selling assets, including stakes in its electric-vehicle and property-management businesses, but has so far made little progress.

CAPITAL MARKETS

Evergrande is the largest high-yield dollar bond issuer in China, accounting for 16 percent of outstanding notes, Bank of America analysts wrote in a note this month.

Should the company collapse, that alone would push the default rate on the country’s junk dollar bond market to 14 percent from 3 percent, they added.

While Beijing has become more comfortable with allowing weaker businesses to fail, an uncontrolled spike in offshore funding costs would risk derailing a key source of financing. It could also undermine global confidence in the country’s issuers at a time when Beijing is pushing for larger foreign investor ownership.

Yields on China’s junk dollar bonds are nearing 14 percent, up from about 7.4 percent in February, a Bloomberg index showed.

The stakes are higher in China, where the credit market is about 15 times the size at US$12 trillion. While Evergrande is less of a whale onshore, a collapse could force banks to cut their holdings of corporate notes and even freeze money markets — the very plumbing of China’s financial system.

In such a credit crunch, the Chinese government or central bank would likely be forced to act. Banks involved in property lending might come under pressure, leading to an increase in soured loans.

Smaller banks exposed to Evergrande or other weaker developers might face “significant” increases in nonperforming loans in the event of a default, Fitch Ratings has said.

ECONOMIC IMPACT

Concern over Evergrande comes at a time when China’s economy is slowing. Aggressive controls to curb COVID-19 outbreaks are hurting retail spending and travel, while measures to cool property prices are taking a toll.

Data earlier this month showed that home sales by value slumped 20 percent last month from a year earlier, the biggest drop since the onset of COVID-19 early last year.

Responding to a question on Evergrande’s potential impact on the economy, Chinese National Bureau of Statistics spokesman Fu Linghui (付凌暉) said that some large property enterprises are running into difficulties and the fallout “remains to be seen.”

China’s priorities of promoting “common prosperity” and deterring excessive risk-taking mean that there is unlikely to be any easing of property curbs this year, Macquarie Group has said.

The sector is likely to be a “main growth headwind” for next year, although policymakers might loosen restrictions to defend growth goals, Macquarie analysts wrote in a note on Sept. 8.

A correction in China’s property market would not only slow the domestic economy, but have global consequences, too.

“A significant slowdown in property construction over the next few years appears probable already, and would become even more likely in the event of an Evergrande failure or bankruptcy,” said Logan Wright, a Hong Kong-based director at research firm Rhodium Group.

“A long-term slowdown in property construction, an industry that represents around a fifth or a quarter of China’s economy by most estimates, would cause a significant decline in GDP growth, commodity demand and would likely have disinflationary effects globally,” Wright said.

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural

Former minister of culture Lung Ying-tai (龍應台) has long wielded influence through the power of words. Her articles once served as a moral compass for a society in transition. However, as her April 1 guest article in the New York Times, “The Clock Is Ticking for Taiwan,” makes all too clear, even celebrated prose can mislead when romanticism clouds political judgement. Lung crafts a narrative that is less an analysis of Taiwan’s geopolitical reality than an exercise in wistful nostalgia. As political scientists and international relations academics, we believe it is crucial to correct the misconceptions embedded in her article,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,

Strategic thinker Carl von Clausewitz has said that “war is politics by other means,” while investment guru Warren Buffett has said that “tariffs are an act of war.” Both aphorisms apply to China, which has long been engaged in a multifront political, economic and informational war against the US and the rest of the West. Kinetically also, China has launched the early stages of actual global conflict with its threats and aggressive moves against Taiwan, the Philippines and Japan, and its support for North Korea’s reckless actions against South Korea that could reignite the Korean War. Former US presidents Barack Obama