The COVID-19 pandemic, rising rates of global poverty and inequality, persistent conflict, and the escalating climate and biodiversity crises are shocks and stresses that contribute to increasing hunger, as well as growing food and nutrition insecurity.

To help tackle this urgent problem more effectively, and make the global food system more stable and resilient, governments should consider establishing a new, multilateral, UN-led food systems stability board (FSSB).

Today, between 720 million and 811 million people — about 10 percent of the world’s population — go to bed hungry every night, and at least 2.4 billion lack access to a healthy and nutritious diet.

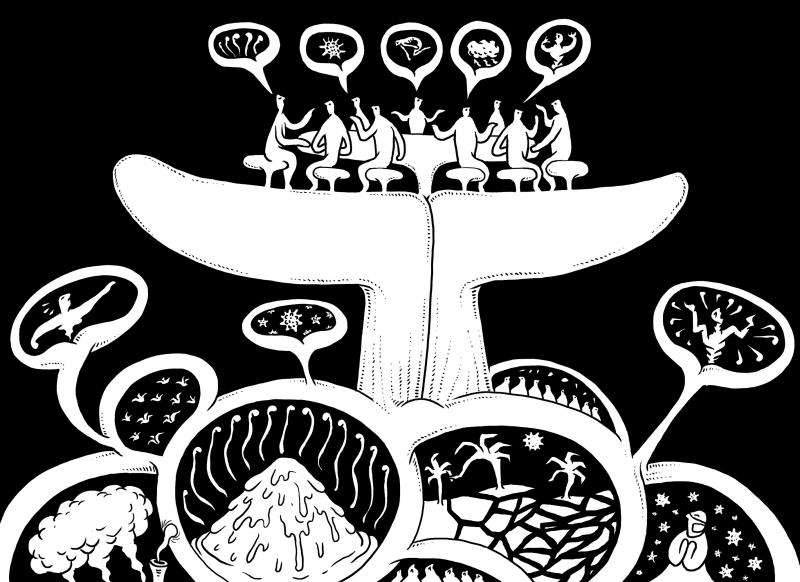

Illustration: Mountain People

Absent major international action, these trends are likely to persist. An Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report last month showed that global warming’s effects have left no region untouched, with significant implications for food systems over the coming decades.

Food systems underpin the security of the global economy, as well as national security in many countries: Hunger and lack of access to food have historically driven civil unrest.

These systems are also among the principal drivers of ecosystem loss and climate change, with agriculture and land-use change responsible for one-quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions.

At the same time, ecosystems such as forests, mangroves and oceans are central to humanity’s efforts to adapt to the climatic changes already under way.

Ensuring the long-term resilience of the global food system will require a significant multilateral collaborative effort. This should build on existing structures and institutions such as the Committee on World Food Security, the Food and Agriculture Organization, the World Food Programme and the World Bank. It will also demand concerted attention from heads of state and government, ministers of finance, and the leaders of multilateral financial institutions.

A quartet of international meetings — the UN Food Systems Summit this month, the G20 summit next month, the UN climate conference in November and the Nutrition for Growth Summit hosted by the Japanese government in December — offer a rare opportunity to focus international attention on the hunger and food-security crisis, and its links to the changing climate. Each of these gatherings could pave the way for the creation of an FSSB of national governments and international organizations working to address this issue.

This could be part of a broader global effort to enhance food governance and achieve — in the words of the Indonesian government, which will hold the G20 presidency next year — a “just and affordable transition toward net-zero” greenhouse gas emissions.

Moreover, there is an encouraging precedent for such a body. The Financial Stability Board (FSB), which was established by the G20 finance ministers in April 2009 with the aim of preventing a repeat of the 2008 global financial crisis, has positively contributed to global macroeconomic stability, and is now an authoritative, independent and well-respected body. Its findings directly influence the decisionmaking of G20 finance ministers, as well as that of the heads of the IMF, the World Bank and regional development banks.

In a similar fashion, an FSSB, if established, would be charged with promoting the health and resilience of the global food system, including by addressing issues such as price stability, trade, strategic reserves and the effects of climate change on production.

The board would fully respect national sovereignty, and not issue legally binding recommendations. Rather, it would give credible advice to governments on how to build a food system that is better prepared to withstand shocks and ensure greater global access to nutritious food.

While governments would decide the precise scope, structure and composition of the FSSB, the body could play a helpful role in several ways.

For example, it could analyze early warning systems and risk-modeling data on hunger, agriculture and climate, including from the Agricultural Market Information System database. It could also advise the WTO and national governments on food-related trade policies, while helping countries respond to changing market dynamics and a volatile climate.

Additionally, the FSSB could support and enable countries to submit voluntary five-year food system risk assessments and resilience plans. It could also gather and share knowledge about global food-trade vulnerabilities, such as those relating to climate change, conflict, lack of crop diversity, pollinator loss and other threats, and identify and review the regulatory, supervisory and voluntary measures needed to address them.

The FSSB could support contingency planning for cross-border crisis management, especially with regard to systemically important food crops or areas particularly affected by climate vulnerability, biodiversity loss, and/or future pandemics.

Lastly, the board could collaborate with the IMF to include more consideration of risks related to climate, biodiversity, and food and land-use systems in the fund’s regular consultations with member countries.

The FSSB could comprise relevant national representatives from ministries of agriculture and rural affairs, trade and commerce, health, environment, and finance, as well as international standard setters and leading scientists in the field of global food-system risks.

As with the FSB, the institution’s audience would be member states, including heads of government, finance ministers and other portfolios.

The absence of an FSSB is a notable gap in the international governance architecture required to bolster the sustainability, equity and resilience of the global food system in this century and beyond. At the UN General Assembly and UN Food Systems Summit — both taking place this month — governments could agree to initiate a one-year consultation process to explore the creation of such a body.

By doing so, they could contribute to a better future for hundreds of millions of vulnerable people — and ensure access to food and security for all.

Sandrine Dixson-Decleve is copresident of the Club of Rome. Jose Antonio Ocampo, a former Colombian minister of finance and UN undersecretary general, is a professor at Columbia University and an ambassador of the Food and Land Use Coalition. Felia Salim, chairwoman of the Partnership for Governance Reform’s board of directors, is an ambassador of the Food and Land Use Coalition.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

It is almost three years since Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) and Russian President Vladimir Putin declared a friendship with “no limits” — weeks before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Since then, they have retreated from such rhetorical enthusiasm. The “no limits” language was quickly dumped, probably at Beijing’s behest. When Putin visited China in May last year, he said that he and his counterpart were “as close as brothers.” Xi more coolly called the Russian president “a good friend and a good neighbor.” China has conspicuously not reciprocated Putin’s description of it as an ally. Yet the partnership

The ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu (孫子) said “know yourself and know your enemy and you will win a hundred battles.” Applied in our times, Taiwanese should know themselves and know the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) so that Taiwan will win a hundred battles and hopefully, deter the CCP. Taiwanese receive information daily about the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) threat from the Ministry of National Defense and news sources. One area that needs better understanding is which forces would the People’s Republic of China (PRC) use to impose martial law and what would be the consequences for living under PRC

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) said that he expects this year to be a year of “peace.” However, this is ironic given the actions of some KMT legislators and politicians. To push forward several amendments, they went against the principles of legislation such as substantive deliberation, and even tried to remove obstacles with violence during the third readings of the bills. Chu says that the KMT represents the public interest, accusing President William Lai (賴清德) and the Democratic Progressive Party of fighting against the opposition. After pushing through the amendments, the KMT caucus demanded that Legislative Speaker

Although former US secretary of state Mike Pompeo — known for being the most pro-Taiwan official to hold the post — is not in the second administration of US president-elect Donald Trump, he has maintained close ties with the former president and involved himself in think tank activities, giving him firsthand knowledge of the US’ national strategy. On Monday, Pompeo visited Taiwan for the fourth time, attending a Formosa Republican Association’s forum titled “Towards Permanent World Peace: The Shared Mission of the US and Taiwan.” At the event, he reaffirmed his belief in Taiwan’s democracy, liberty, human rights and independence, highlighting a