For two decades Chinese tech firms have flocked to the US stock market, drawn by a friendly regulatory environment and a vast pool of capital eager to invest in one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

Now, the juggernaut behind hundreds of companies worth US$2 trillion appears stopped in its tracks.

Beijing’s July 10 announcement that almost all businesses trying to go public in another country would require approval from a newly empowered cybersecurity regulator amounts to a death knell for Chinese initial public offerings (IPOs) in the US, long-time industry watchers have said.

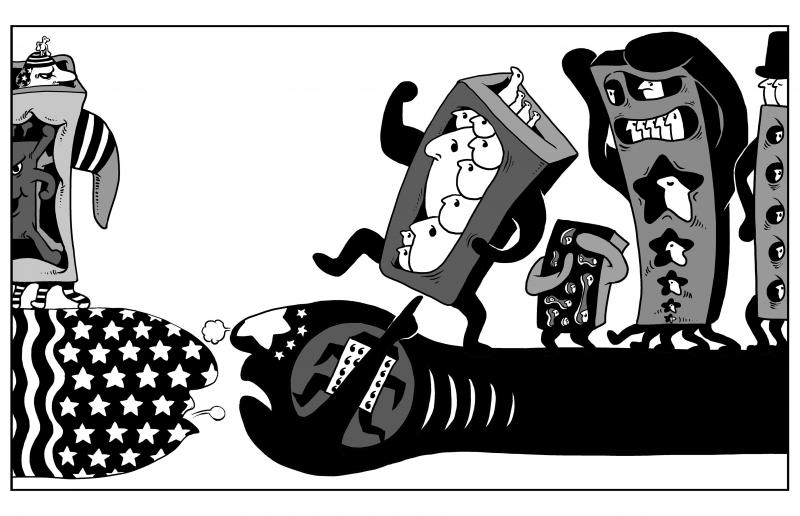

Illustration: Mountain People

“It’s unlikely there will be any US-listed Chinese companies in five to 10 years, other than perhaps a few big ones with secondary listings,” said Paul Gillis, a professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management in Beijing.

The clampdown, triggered by Didi Global Inc’s decision to push ahead with a New York listing despite objections from regulators, is sending shock waves through markets.

A gauge of US-traded Chinese stocks has dropped 30 percent from its recent high. For investors in companies that have yet to list, there is growing uncertainty over when they might get their money back. Wall Street firms are bracing for lucrative underwriting fees to dry up, while Hong Kong is set to benefit, as Chinese companies look for alternative — and politically safer — venues closer to home.

It is difficult to overstate the importance that US markets have held for Chinese firms. The first wave began selling American depositary receipts (ADRs) — surrogate securities that allow investors to hold overseas shares — in 1999. Since then more than 400 Chinese companies picked US exchanges for their primary listings, raising more than US$100 billion, including most of the country’s technology industry. Their stocks later benefited from one of the longest bull markets in history.

Hong Kong-based Web site operator China.com Corp began the trend when it went public on the NASDAQ Composite in 1999 during the dotcom bubble. The stock, under the symbol CHINA, surged 236 percent on its debut, enriching founders and backers, and showing Chinese Internet firms a pathway to foreign capital — if they could only find a way around the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) strict regulatory controls.

Unlike companies in Hong Kong, whose laissez-faire approach to business meant that there were few rules on company fundraising, mainland-based private enterprises faced much higher hurdles. Foreign ownership in many industries, especially in the sensitive Internet industry, was restricted, while an overseas listing required approval from the Chinese State Council, or Cabinet.

To get around these obstacles, a compromise was found in the shape of a variable interest entity (VIE) — a complex corporate structure used by most ADRs, including Didi and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. Under a VIE, which was pioneered by now-private Sina Corp in 2000, Chinese companies are turned into foreign firms with shares that overseas investors can buy.

Legally shaky and difficult to understand, this solution nonetheless proved acceptable to US investors, Wall Street and the CCP alike.

Back in China, the government was taking steps to modernize its stock market, which only reopened in 1990, having been shut 40 years earlier. In 2009, the country launched the NASDAQ-style ChiNext board in Shenzhen.

When Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) came to power in 2013 access to the outside world was greatly increased, including exchange trading links with Hong Kong that allowed foreign investors to buy mainland equities directly. In 2018, China began a trial program to rival ADRs, but it failed to gain traction.

The most radical step came in 2019 when Shanghai opened a new stock venue called the STAR board, which minimized red tape, allowed unprofitable companies to list onshore for the first time, and got rid of a cap on first-day price moves. It also scrapped an unwritten valuation ceiling that forced firms to sell their shares at 23 times earnings or less.

However, mainland exchanges still do not allow dual-class shares, which are popular with tech firms because they give founders more voting power. Hong Kong introduced the structure in 2018.

The goal was to create an environment that would enable Chinese tech firms to list successfully at home, and be less reliant on US capital. This need became all the more pressing as tensions between Beijing and Washington increased during the latter part of former US president Donald Trump’s term in office. Trump introduced tough new rules that might oust Chinese firms from exchanges in a few years’ time if they refused to hand over financial information to US regulators.

While secondary listings in Hong Kong picked up, Chinese firms still preferred New York, where it takes weeks rather than months to process an IPO application. China’s strict capital controls meant that domestic exchanges could not compete with New York on liquidity and higher valuations for firms.

China Inc raised US$13 billion through first time share sales in the US this year alone.

After Didi’s contentious June 30 IPO, it appears the CCP decided that it had had enough.

“The death of ADRs was inevitable,” said Fraser Howie, author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundation of China’s Extraordinary Rise.

“What’s interesting is the mold and template that’s achieving that result,” Howie said. “It’s coming from a mindset of control and clamping down on business. That’s very different to a mindset of reform and building markets domestically.”

Beijing’s move to regulate overseas IPOs coincides with stricter controls over China’s technology firms, many of which have near-monopolies in their fields and vast pools of user data. This campaign to rein in the tech industry has accelerated in recent months, as Xi seeks to limit the influence of the billionaires who control these firms.

For Chinese companies listed in the US, what happens next largely depends on what China does with VIEs. Banning them outright would be unlikely, as it would force firms to delist from foreign exchanges, unwind that structure and then relist — a costly process that could take years.

The updated regulations are expected to be ready in one or two months, people familiar with the matter have said.

Hong Kong is increasingly looking like a viable alternative. For one, China plans to exempt Hong Kong IPOs from first seeking the approval of the country’s cybersecurity regulator, Bloomberg reported last week.

In a forced US delisting, firms that already sold shares in Hong Kong — such as Alibaba and JD.com — could migrate their primary listing to the territory. The delisted US receipts, which could still trade off-exchange, would not be worthless because they represent an economic interest in the company. Hong Kong’s open markets and greenback-pegged currency should facilitate the conversion.

Holders could sell their ADRs before they are delisted or convert them into the Hong Kong-listed common stock without much disruption. A company choosing to terminate its ADR program entirely could also pay out a dollar amount to investors.

However, the outlook for Hong Kong’s role as a global financial center is looking more uncertain in the wake of a warning by US President Joe Biden’s administration about doing business in the territory. On Monday, an index of Chinese shares in Hong Kong fell 1.9 percent, taking its loss since a January peak to about 19 percent.

Regardless, the two-decade era that saw China’s most successful and powerful private firms list in the US is coming to a close. The message from Beijing is clear: The CCP will have the final say on everything, including IPOs.

“It’s really important to own companies that are aligned with the direction of the Chinese government,” said Tom Masi, coportfolio manager of GW&K Investment Management’s emerging wealth strategy fund, which has half of its money invested in Chinese stocks.

“I would not be financing firms that are going to circumvent anything that the Chinese government wants to accomplish,” Masi said.

The recent passing of Taiwanese actress Barbie Hsu (徐熙媛), known to many as “Big S,” due to influenza-induced pneumonia at just 48 years old is a devastating reminder that the flu is not just a seasonal nuisance — it is a serious and potentially fatal illness. Hsu, a beloved actress and cultural icon who shaped the memories of many growing up in Taiwan, should not have died from a preventable disease. Yet her death is part of a larger trend that Taiwan has ignored for too long — our collective underestimation of the flu and our low uptake of the

For Taipei, last year was a particularly dangerous period, with China stepping up coercive pressures on Taiwan amid signs of US President Joe Biden’s cognitive decline, which eventually led his Democratic Party to force him to abandon his re-election campaign. The political drift in the US bred uncertainty in Taiwan and elsewhere in the Indo-Pacific region about American strategic commitment and resolve. With America deeply involved in the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, the last thing Washington wanted was a Taiwan Strait contingency, which is why Biden invested in personal diplomacy with China’s dictator Xi Jinping (習近平). The return of

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has long been a cornerstone of US foreign policy, advancing not only humanitarian aid but also the US’ strategic interests worldwide. The abrupt dismantling of USAID under US President Donald Trump ‘s administration represents a profound miscalculation with dire consequences for global influence, particularly in the Indo-Pacific. By withdrawing USAID’s presence, Washington is creating a vacuum that China is eager to fill, a shift that will directly weaken Taiwan’s international position while emboldening Beijing’s efforts to isolate Taipei. USAID has been a crucial player in countering China’s global expansion, particularly in regions where

Actress Barbie Hsu (徐熙媛), known affectionately as “Big S,” recently passed away from pneumonia caused by the flu. The Mandarin word for the flu — which translates to “epidemic cold” in English — is misleading. Although the flu tends to spread rapidly and shares similar symptoms with the common cold, its name easily leads people to underestimate its dangers and delay seeking medical treatment. The flu is an acute viral respiratory illness, and there are vaccines to prevent its spread and strengthen immunity. This being the case, the Mandarin word for “influenza” used in Taiwan should be renamed from the misleading