The clandestine clinic was under fire, and the medics inside were in tears.

Hidden away in a Burmese monastery, this safe haven had sprung up for those injured while protesting the military’s overthrow of the government, but security forces had discovered its location.

A bullet struck a young man in the throat as he defended the door, and the medical staff tried frantically to stop the hemorrhaging. The floor was slick with blood.

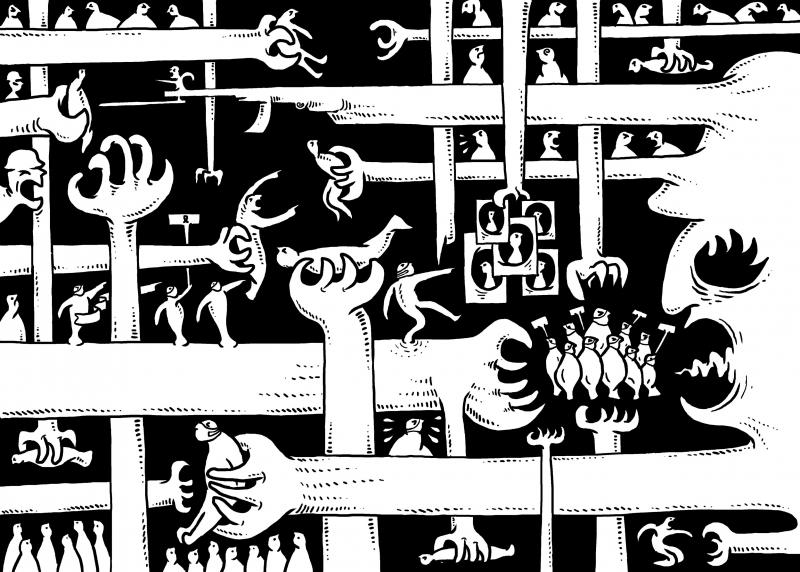

Illustration: Mountain People

In Myanmar, the military has declared war on healthcare — and on doctors, who were early and fierce opponents of the takeover in February. Security forces are arresting, attacking and killing medical workers, dubbing them enemies of the state. With medics driven underground amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the country’s fragile healthcare system is crumbling.

“The military is purposely targeting the whole healthcare system as a weapon of war,” said one Yangon doctor on the run for months, whose colleagues at an underground clinic were arrested during a raid. “We believe that treating patients, doing our humanitarian job, is a moral job... I didn’t think that it would be accused as a crime.”

Inside the clinic that day, the young man shot in the throat was fading. His sister wailed. A minute later, he was dead.

One of the clinic’s medical students — whose name, like those of several other medics, has been withheld to protect her from retaliation — began to sweat and cry. She had never seen anyone shot.

Now she, too, was at risk. Two protesters smashed the glass out of a window so that the medics could escape.

“We are so sorry,” the nurses told their patients.

One doctor stayed behind to finish suturing the patients’ wounds. The others jumped through the window and hid in a nearby apartment complex for hours. Some were so terrified that they never returned home.

“I cry every day from that day,” the medical student said. “I cannot sleep. I cannot eat well. That was a terrible day.”

The suffering caused by the military’s takeover of this nation of 54 million has been relentless. Security forces have killed at least 890 people, including a six-year-old girl that they shot in the stomach, said the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), which monitors arrests and deaths in Myanmar.

About 5,100 people are in detention and thousands have been forcibly disappeared. The military, known as the Tatmadaw, and police have returned mutilated corpses to families as tools of terror.

Amid all of the atrocities, the military’s attacks on medics, one of the most revered professions in Myanmar, have sparked particular outrage.

Myanmar is now one of the most dangerous places on earth for healthcare workers, with 240 attacks this year — nearly half of the 508 globally tracked by the WHO. That is by far more than any other country.

“This is a group of folks who are standing up for what’s right and standing up against decades of human rights abuses in Myanmar,” US-based Physicians for Human Rights advocacy director Raha Wala said. “The Tatmadaw is hell-bent on using any means necessary to quash their fundamental rights and freedoms.”

The military has issued arrest warrants for 400 doctors and 180 nurses, with photographs of their faces plastered all over state media like “Wanted” posters. They are charged with supporting and taking part in the “civil disobedience” movement.

At least 157 healthcare workers have been arrested, 32 wounded and 12 killed since Feb. 1, said Insecurity Insight, which analyzes conflicts around the globe.

Over the past few weeks, arrest warrants have increasingly been issued for nurses.

Burmese medics and their advocates have said that these assaults contravene international law, which makes it illegal to attack health workers and patients, or deny them care based on their political affiliations.

In 2016, after similar attacks in Syria, the UN Security Council passed a resolution demanding that medics be granted safe passage by all parties in a war.

“In other country’s protests, the medics are safe. They are exempt. Here, there are no exemptions,” said Nay Lin Tun, a physician who has been on the run since February and now provides care covertly.

Medics are targeted by the military because they are not only highly respected, but also well-organized, with a strong network of unions and professional groups. In 2015, doctors pinned black ribbons to their uniforms to protest the appointment of military personnel to the Burmese Ministry of Health. Their Facebook page quickly gained thousands of followers, and the military appointments stopped.

This time, the protest by medics started days after the military ousted democratically elected leaders, including civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi, from power. From remote towns in the northern mountains to the main city of Yangon, they walked off their jobs on military-owned facilities, pinning red ribbons to their clothes.

The response from the military was fierce, with security forces beating medical workers and stealing supplies.

Security forces have occupied at least 51 hospitals since the takeover, Insecurity Insight, Physicians for Human Rights and the Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health and Human Rights said.

On March 28, during a strike in the city of Monywa, a nurse was fatally shot in the head, the AAPP said.

On May 8, hundreds of kilometers away in northern Kachin state, a doctor was arrested, tied up and also fatally shot in the head when passing a military base.

Rather than acknowledging its attacks on medical workers, the military has accused them of genocide for not treating patients.

“They are killing people in cold blood. If this is not genocide, what shall I call it?” Deputy Minister of Information Major General Zaw Min Tun told an April 9 news conference broadcast live on national television.

A military spokesperson responded to written questions only by sending an article that blamed supposed election fraud for the country’s problems.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy, won an election in November last year by a landslide, and independent poll watchers have largely found that it was free of significant issues.

The crackdown on healthcare is hitting a vulnerable system at a critical time.

In 2018, before the takeover, Myanmar had just 6.7 physicians per 10,000 people — significantly lower than the global average of 15.6 in 2017, the World Bank said.

Now, testing for COVID-19 has plummeted, and the vaccination program has stalled, with its former head, Htar Htar Lin, arrested and charged with high treason last month.

Even if vaccines are available, people are afraid of being arrested just by going to the hospital, one medic said.

Given the military’s crackdown on information, there are no independent figures on current COVID-19 cases and deaths. The state media has reported almost 160,000 cases and 3,347 deaths, but experts have said that is an undercount. There are clear signs that another COVID-19 surge is happening in the country.

“What we’re seeing is really a human rights emergency that is turning into a public health disaster,” said Jennifer Leigh, an epidemiologist and Myanmar researcher for Physicians for Human Rights. “We’re definitely seeing echoes of what happened in Syria, where health workers and the health facility was systematically targeted.”

The crackdown has forced doctors to make excruciating choices and find new ways to reach patients.

As an emergency physician at a government hospital, Zaw had been on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19. In January, the first vaccines arrived from India, giving the exhausted doctor a rush of hope, but after months of fighting the virus, she found herself instead fighting for democracy.

Going on strike was an agonizing decision. As a doctor, she believed in caring for those in need, but doing so meant working for and legitimizing the generals who overthrew the government.

The solution was providing care in secret, said Zaw, who is identified by a partial name to protect her from retaliation.

In February, she helped set up a clinic tucked away in another monastery in another part of Myanmar, with supplies donated from a COVID-19 facility where she had previously volunteered.

A generator keeps the equipment running during the frequent power cuts. Select contacts in nearby townships who know the clinic’s location direct the sick and wounded there.

Zaw fled the housing that the government provides public doctors. She has since moved three times to avoid detection, and sent her family to a safe house.

Now, she lives above the clinic, sleeping alongside seven other doctors and nurses on mats separated only by curtains. It has become too risky to leave the compound — she knows that the soldiers are hunting for the clinic, and for her.

“Because of them, our hopes, our dreams are hopeless,” she said. “Some of the medical students and some of our doctors are dying because of them.”

Sometimes, Zaw and her colleagues are tipped off by informants the night before a raid, giving them time to dismantle the clinic and hide the equipment.

However, one day, they only had time to hide themselves. There was almost no warning, just the frantic shouts of monks that soldiers were at the gate.

Zaw raced to a nearby building with her colleagues. Moments later, she watched through a window as soldiers stormed her clinic, frightening the patient that she had just been treating for hypertension and diabetes. Normally shy and soft-spoken, she fought the urge to run out and hit them.

Volunteers told the soldiers that no government doctors were working there. The soldiers eventually left, and Zaw returned to her patient.

She knows that she was lucky that day, but she intends to keep treating the sick — even if her efforts end in her death.

“All people have to die one day,” Zaw said. “So I’m prepared.”

While some medics have gone underground, others have fled the cities to live in the border areas.

Before the military takeover, it was difficult to persuade government doctors from the cities to work in states like Kachin, where ethnic armed groups have long battled the Tatmadaw, the founder of an underground clinic and medical training organization there said.

However, since February, government doctors have come to Kachin to provide care and train others in emergency medicine, said the founder, who spoke anonymously to avoid retaliation.

The group now has 20 to 30 trainers.

Their clinic shifts locations constantly, sometimes operating out of a tent. The medics treat the injured from landmines, homemade bombs and battles with security forces.

The fear of being discovered is intense. A new vehicle parked in front of his house and new faces in the neighborhood make the founder anxious. His wife has packed emergency bags filled with clothing, supplies and cash.

Security forces recently abducted someone from in front of one medic’s home, he said, and were probably looking for the medic.

“Every day since I started doing this, I know my life is in danger,” he said.

The war on medics is taking a severe toll on those who need healthcare, especially the young.

Under a tarp in the jungle pounded by relentless rain, 20-year-old Naing Li stared helplessly at her firstborn child, just five days old. The newborn’s breathing had grown labored, and his tiny body felt like it was on fire.

She could do nothing. Her husband was back in their village in western Myanmar, near the embattled town of Mindat, fighting advancing soldiers.

There were no medics around to help — not here in the jungle where she had fled with her baby, and not in their village either.

The baby is among about 600,000 newborns who are not receiving essential care, putting them at risk of illness, disability and death, the UN International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) said.

One million children are lacking routine immunizations. Nearly 5 million are not receiving vitamin A supplements to prevent infection and blindness, and more than 40,000 are no longer getting treated for malnutrition.

At the same time, COVID-19 is spreading rapidly along Myanmar’s porous border with Bangladesh, India and Thailand, alarming health experts.

“This has the potential of turning into a very big and very bad public health crisis,” UNICEF representative to Myanmar Alessandra Dentice said.

Naing Li and her baby had survived one crisis: a difficult labor at home. They had not been able to go to a hospital in nearby Mindat, where the military launched a bloody assault and declared martial law.

Little Mg Htan Naing was healthy when he was born on May 16, but five days later, in the jungle, the swaddled infant struggled to breathe.

By the next morning, Naing Li was desperate enough to risk returning home for help, but when she arrived, she found her husband, 23-year-old Naing Htan, struck in the back by shrapnel.

The couple could only watch as their son slipped away. At 11am, Mg Htan Naing died in his mother’s arms.

Men in Myanmar are not supposed to cry in front of others, but the father could not contain his grief.

“I cried out loud in agony, even though I am a man,” he said.

Even if the couple had found a doctor in time, they would likely have faced the challenge of finding medicine.

Healthcare workers said that soldiers are blocking aid, and have confiscated medical equipment and drugs from clinics during raids.

A Mindat resident, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that she and her family stored medicine before the fighting broke out, but with water supplies cut and no way to properly clean themselves, they worry about diseases.

“It is very difficult here,” she said. “If we get sick, we cannot go to the clinic. We have to take whatever medicine we have at home.”

The collapse of the public hospital system has put pressure on aid groups.

In Shan and Kachin states, Doctors Without Borders has taken on more than 3,045 patients who would otherwise have been treated under the government’s AIDS program. The clinics have been forced to reduce the amount of HIV/AIDS medicine distributed to patients from a three-month supply to a one-month supply.

Many aid groups have shut down or drastically scaled back operations.

After the military takeover, aid groups stopped coming to a camp for 1,000 displaced people in Kachin state, a women’s rights advocate said.

A weekly free government clinic closed. The children and older people are experiencing diarrhea and malnourishment. There is no one to perform surgeries or deliver babies. Food is scarce, and most people are relying on traditional medicines.

“We are barely scraping by,” she said. “I feel death is just around the corner for us.”

For countless others, like Mg Htan Naing, death has come. The baby’s parents buried him in their garden, and then fled.

His father blames his son’s death not on the doctors on strike, but on the soldiers who drove them from Mindat.

The country’s caretakers of the sick and wounded are haunted by the people they could have saved if only they had not been under attack.

“Given the chance, we could have stopped the bleeding, we could have saved patients and we could have prevented deaths — it hurts,” the Yangon doctor said. “The people dying are not just nobodies. They are our country’s future generations.”

The return of US president-elect Donald Trump to the White House has injected a new wave of anxiety across the Taiwan Strait. For Taiwan, an island whose very survival depends on the delicate and strategic support from the US, Trump’s election victory raises a cascade of questions and fears about what lies ahead. His approach to international relations — grounded in transactional and unpredictable policies — poses unique risks to Taiwan’s stability, economic prosperity and geopolitical standing. Trump’s first term left a complicated legacy in the region. On the one hand, his administration ramped up arms sales to Taiwan and sanctioned

World leaders are preparing themselves for a second Donald Trump presidency. Some leaders know more or less where he stands: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy knows that a difficult negotiation process is about to be forced on his country, and the leaders of NATO countries would be well aware of being complacent about US military support with Trump in power. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu would likely be feeling relief as the constraints placed on him by the US President Joe Biden administration would finally be released. However, for President William Lai (賴清德) the calculation is not simple. Trump has surrounded himself

US president-elect Donald Trump is to return to the White House in January, but his second term would surely be different from the first. His Cabinet would not include former US secretary of state Mike Pompeo and former US national security adviser John Bolton, both outspoken supporters of Taiwan. Trump is expected to implement a transactionalist approach to Taiwan, including measures such as demanding that Taiwan pay a high “protection fee” or requiring that Taiwan’s military spending amount to at least 10 percent of its GDP. However, if the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) invades Taiwan, it is doubtful that Trump would dispatch

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) has been dubbed Taiwan’s “sacred mountain.” In the past few years, it has invested in the construction of fabs in the US, Japan and Europe, and has long been a world-leading super enterprise — a source of pride for Taiwanese. However, many erroneous news reports, some part of cognitive warfare campaigns, have appeared online, intentionally spreading the false idea that TSMC is not really a Taiwanese company. It is true that TSMC depositary receipts can be purchased on the US securities market, and the proportion of foreign investment in the company is high. However, this reflects the