Protesting alone outside an Australian hospital where the son of Myanmar’s attorney general works as a doctor, Burmese electrical engineer Susu San is determined to let the military junta know that their children are to be hounded wherever they go.

The 33-year-old woman was difficult to miss as she stood in the hospital parking lot, dressed in a pink track suit, one hand raised in a three-fingered salute of resistance and the other clutching a placard calling for the junta to release deposed Burmese State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi.

“They think they are untouchable,” said Susu San, having traveled 1,500km from the northern tip of Queensland to the workplace of one of the “junta children” at a hospital in the city of Mackay.

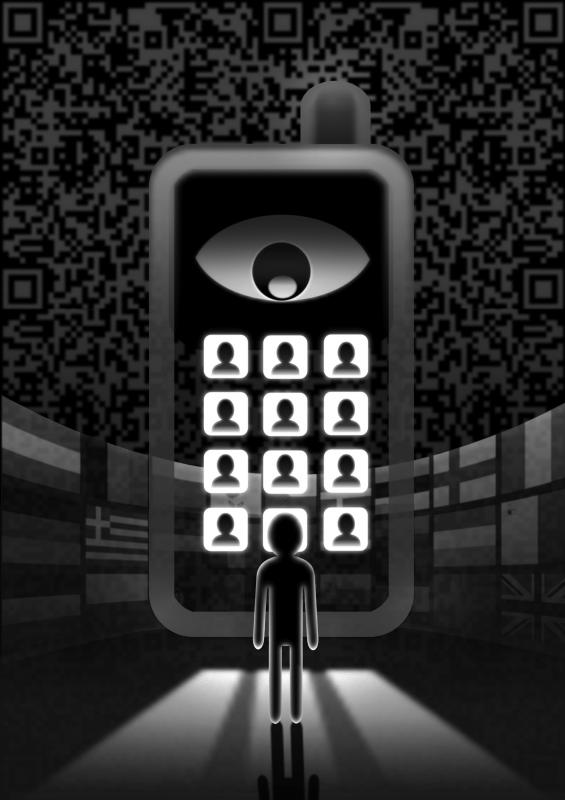

Illustration: Yusha

“This is a way to empower our people by saying that no one can escape from lawlessness and brutality,” she added.

Since the coup, some protesters have launched an online campaign to denounce family members and associates of the junta in Myanmar and beyond — and spotlight those living comfortably in democratic nations far from the bloody chaos at home.

Organizers say that it is a nonviolent way to pressure the junta to reverse the coup and return Myanmar to democracy.

“The military understands one language — that is pressure,” said Tun Aung Shwe, a member of the Burmese community in Australia who was among a group that has gone to Canberra to urge the government to sanction people affiliated with the junta.

“Social punishment is effective as it shakes up the junta, getting them to rethink what they are doing,” Tun Aung Shwe said.

Repeated calls to the military and government seeking comment were unanswered.

Activists — aside from shaming friends, associates and kin of the junta on social media — have created a Web site called socialpunishment.com, from which information has been widely shared on Facebook.

The Web site features more than 120 profiles of people who are accused of failing to speak out against a coup that has halted 10 years of democratic reform and brought bloody suppression.

It ranks them on a “traitor” scale from high to low, and there are photographs of the profiled person as well as details of their associations and whereabouts on the globe, making it easy for Burmese in those countries to track them down.

As of 2016, nearly 33,000 people from Myanmar lived in Australia alone.

Susu San said that her target at the Mackay Base Hospital was 28-year-old doctor Min Ye Myat Phone Khine.

The Web site said that his mother is Burmese Attorney General Thida Oo, whose office is crafting a legal case against Aung San Suu Kyi. She had served as a permanent secretary in the attorney general’s office during the civilian government, and her acceptance of a role in the junta was seen as a deep betrayal by Aung San Suu Kyi’s supporters.

Neither has responded to requests for comment, but two days after Susu San’s protest, Min Ye Myat Phone Khine posted messages for the first time on Facebook since the coup, saying that he supported the pro-democracy movement.

“I have come out of the shadow of my parents to walk my own path,” he wrote on March 8. “I will stand boldly with the people because I am only one citizen seeking to achieve a true and fair democracy.”

ETHICAL DOUBTS

Although the campaign against the children of the junta has raised questions among some participants over the ethics of shaming people online because of the actions of their parents, anger over mass arrests and killings during anti-coup protests has outweighed those qualms, campaigners said.

An advocacy group, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, said that security forces have so far killed more than 224 people.

This number could not be independently confirmed.

Susu San grappled with the ethical complexities of targeting “junta children,” as she calls them, but ultimately decided in her mind that it was “fair,” given the number of Burmese being gunned down in the streets.

Min Ye Myat Phone Khine’s earlier failure to speak out against the coup on his social media accounts persuaded Susu San that he was fair game.

The US has imposed sanctions on two children of Burmese Army Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and six companies that they control. Britain has sanctioned more than half a dozen generals, banning entry and freezing assets, while Canada said that it would take action against nine military officials.

The junta has not responded to the imposition of these sanctions, but had earlier said that it had expected sanctions and was not worried by them.

In Australia, some in the Burmese community are campaigning for the government to sanction children of members of the junta by freezing their assets or revoking their visas.

An Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade spokesperson was unable to comment on whether the agency was considering sanctions against any more people.

Some people targeted in Australia have had their personal information — telephone numbers, places of work and suburbs where they live — published online.

The campaign to shame the junta is an extension of a wider campaign to boycott military-run companies and isolate individuals who back the coup.

This broader campaign, which was inspired by the protest movement, has four pillars: “Don’t sell anything to them,” “Don’t buy anything from them,” “Don’t associate with them” and “We will never forget.”

Amara Thiha, a Burmese fellow at the US-based Stimson Center think-tank, said that there have been signs that going after individuals online could prove counterproductive.

He said that the language and threats used by soldiers and their supporters on social media is hardening as the pressure increases.

‘PUNISH ME’

Bryan Tun, the son of Burmese Minister of Commerce Pwint San, is also working as a doctor in Australia.

Although not listed on the Web site, Tun said that he has been abused on social media even though he is a longtime supporter of Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, posts messages of support for the protest movement and disagrees with his father politically.

“I have been socially punishing him since this thing happened. I have been openly protesting against him,” said Tun, 28, a doctor at Redland Hospital in Queensland.

Pwint San could not be reached for comment.

Despite his experience, Tun said that he still believes that the online campaign is a valid act of resistance.

“I think that is one of the very few weapons that people have,” he said. “They [the military] are killing people on the streets with guns.”

However, some targets of the online campaign feel victimized.

One of the first to be attacked online was Nan Lin Lae Oo, a student that the social punishment campaign identified as the daughter of Burmese Army Major General Kyaw Swar Lin.

Dubbed a “murderer’s daughter,” pictures of her were plastered around the Toyo University campus in Tokyo, where she is studying. Burmese advocates have urged the university to expel her.

The general and his daughter could not be reached for comment. The Burmese military has not answered calls.

Toyo University spokesman Masakazu Saito said that the university has consulted with police, but declined to comment further, citing concerns for the student’s safety.

The police declined to comment.

Some parents have made impassioned pleas on social media, such as the wife of a retired senior military officer, Htin Zaw Win, whose daughter was identified on Facebook as a student at Yangon’s University of Medicine 1 by the Civil Disobedience Movement Naming and Shaming.

“You can do any kind of social punishment to me, the mother,” Khin Khin Aye Cho wrote on Facebook. “If it will satisfy you to beat both parents to death, then I will accept anytime and I will sacrifice my blood for my daughter.”

“Please allow my daughter, the daughter of retired military family, Ayebhone Pyaecho’s life to grow,” she wrote.

The family could not be contacted. They have stayed off social media since that post.

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural