In his navy suit and blue tie, Malcolm George looked every bit the part as he launched his Liberal Party-endorsed campaign for a seat in the Western Australian parliament back in 2016.

A now defunct candidate Web site lists his priorities for the Baldivis electorate on Perth’s suburban fringe as “a stronger local police presence,” “local job opportunities” and “increased recreational facilities for young families.”

Four years later, the anodyne political cliches are gone. Instead, George’s online life ranges from misinformation and conspiracy theory to posts about the Essendon soccer club.

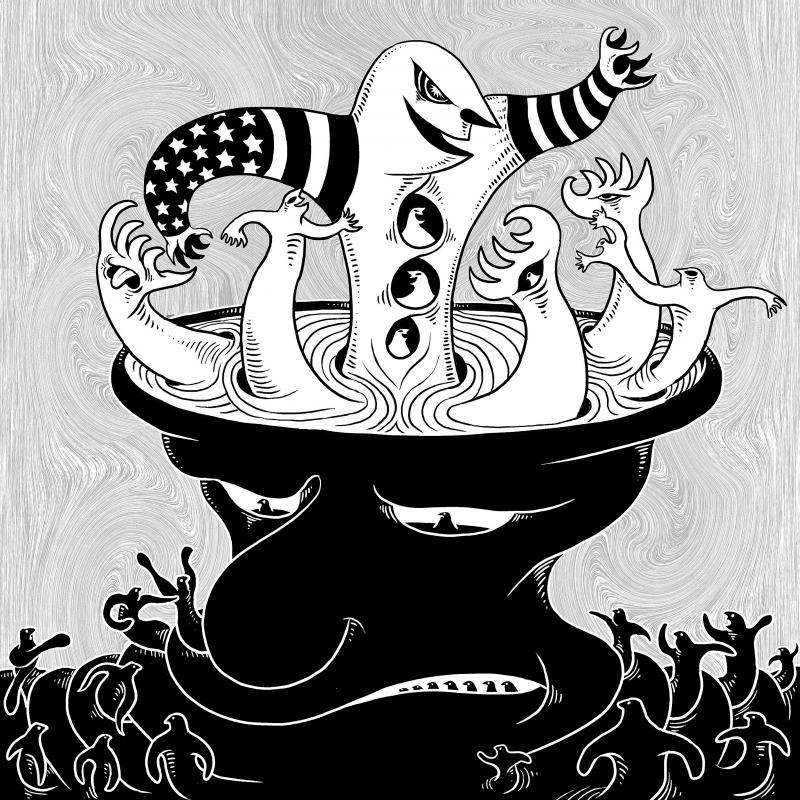

Illustration: Mountain People

On his Facebook page, videos of Sky News’ Rowan Dean railing against the so-called “great reset” sit alongside assertions that the US Democrats will institute “one world government,” while evangelical pastors claiming former US president Donald Trump as the rightful US president are shared with invocations of the rhetoric of the QAnon conspiracy theory.

A devout evangelical Christian, George last year participated in an online “boot camp” run by the US-based Home Congregations Network, which is part of a broader movement of spiritual organizations that reinterpret QAnon through the lens of the Bible.

“Donald Trump will serve the next four years as President! [US President Joe] Biden is guilty of treason and willl [sic] be arrested at some point along with [former US president Barack] Obama, [former US president] Bill and [former US secretary of state] Hilary [sic] Clinton and many other deep state operatives!” he wrote on Jan. 1.

Still an active member of the Western Australian Liberal Party, George is an example of the steady rise of what he called — borrowing from former Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway — “alternate facts,” and of Australia’s vulnerability to the same forces that have caused so much carnage in the US during the past few years.

In an interview with the Guardian last month, George confirmed he was now the Australian contact for the Home Congregations Network — a “minor” role that he declined to expand on.

However, he said that although he is “interested” in QAnon, he is not a “follower.”

“I’m not someone who is waiting for the next Q drop [and] there is a lot more information out there which I think is more interesting than whatever they might say. Am I someone who has taken an interest in Q? Am I someone who has heard what they’ve got to say? Yes, but I’m not like a card-carrying member of the Q movement,” he said.

George said he did not believe the Home Congregations Network was linked to QAnon — despite its Web site and sermons regularly sharing material linked to the conspiracy.

“I take an interest in a wide array of media sources, including alternative media,” he said.

RISE OF CONSPIRACY

While the role of conspiracy theories, and particularly QAnon, in the lead-up to the attack on the Capitol in Washington on Jan. 6 helped to mark an inflection point in the US, Australia has been slower to recognize the threat those movements pose.

It is difficult to measure the spread and influence of conspiracy movements among the broader Australian population, but polling from last year offers some insight into its influence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

An Essential poll carried out in May last year found a significant number of people — 39 percent — believed COVID-19 was “engineered and released from a Chinese laboratory in Wuhan.”

A smaller — but consistent — rump of people polled also believed that Microsoft founder Bill Gates had “played a role in the creation and spread of COVID-19” (13 percent), the virus was “not dangerous and is being used to force people to get vaccines” (13 percent), and that 5G was being used to spread the virus (12 percent).

Underpinning much of the spread of conspiracy theories and misinformation in the US has been the dramatic rise of QAnon, a cult-like movement that claims without any evidence that during his presidency, Trump had secretly worked to thwart a cabal of elites made up of Democrats, Hollywood celebrities and billionaires who run the world while engaging in pedophilia, human trafficking and ritualistic child sacrifice.

A December NPR/Ipsos poll found that 17 percent of US adults believed “a group of Satan-worshiping elites who run a child sex ring are trying to control our politics and media.” Another 37 percent said they did not know whether it was true or not.

Studies have shown that Australians are also among the theory’s largest proponents. Last year, the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) released a report that found QAnon’s following had grown considerably in Australia last year, with Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Twitter driving increased engagement.

The report found that Australia was the fourth-largest country for QAnon activity, behind the US, UK and Canada. Its presence in Australia is also evident on less mainstream sites.

For example, as Canadian QAnon research Marc-Andre Argentino has pointed out, there were at least six Australian Q “research boards” on the site 8kun, with about 4,000 posts by January last year. That had increased to 11 boards by the start of this year.

Last year, Guardian Australia revealed that QAnon had found a follower in Tim Stewart, a family friend of Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison. Stewart was behind one of Australia’s largest QAnon-linked accounts, BurnedSpy34.

Stewart, whose wife worked as part of the prime minister’s staff, gained a significant following online thanks to his involvement in the conspiracy, and, as Crikey has previously reported, celebrated along with other Q followers when Morrison used the word “ritual” abuse in his formal apology to the survivors of institutional child abuse.

The response to the revelation from government was muted. Officials inside the Department of Premier and Cabinet told a Senate hearing they had not briefed the prime minister on the conspiracy theory, despite the FBI’s decision to identify it as a potential domestic terror threat.

Department Deputy Secretary Stephanie Foster also told the hearing she was not aware Stewart’s account had been suspended by Twitter for “engaging in coordinated harmful activity.”

QANON’S GLOBAL SPREAD

One of the most confounding aspects of QAnon’s global spread is its specificity to the US — the anonymous Q whose “drops” guide the cult’s bizarre theories purports to be a government insider with top security clearance, and the vast majority of its theories pertain to that country’s domestic politics.

Yet audiences in Australia have proven more than capable of adapting it to their context. For example, during Melbourne’s COVID-19 outbreak last year, QAnon adherents pushed the baseless theory that the city’s lockdown was a cover to allow children stolen from their families to be trafficked through secret tunnels under the city.

Similarly, a 2015 video of former Liberal Party senator Bill Heffernan unsuccessfully attempting to submit a list of names of 28 prominent Australians he alleged were pedophiles during the royal commission into institutional responses to child sexual abuse is now a key plank of the cult’s canon in Australia, offered as evidence of attempts to cover up widespread child abuse.

Part of that adaptability might be a function of how heavily the tenets of QAnon borrow from a long history of conspiratorial thinking. While QAnon might have begun in 2017 as a spin-off of the Pizzagate conspiracy, its themes are a continuation of conspiratorial movements that predate the Internet, as well as the consolidation of several other theories originating in the live action role play game culture of Internet message boards such as 4chan.

The ISD report also points to a blurring of the lines between conspiracies, so that the bizarre theories at the center of QAnon have blended with the anti-vaccine movement, 5G conspiracies and other “antisemitic and anti-migrant tropes.”

That trend was especially evident in Australia during Melbourne’s long COVID-19 lockdown last year, when a string of protests organized by a loose collection of conspiracy groups led to dozens of arrests last year.

At various gatherings, eclectic crowds of people waved signs aligned to a broad mix of causes, including QAnon and 5G, as well as calling for the arrest of Gates because of his involvement in the production of a coronavirus vaccine.

Peter Trute, the former editor of the Australian Associated Press FactCheck who worked on addressing misinformation for the wire service until August last year, said that during COVID-19, a broad overlap between anti-5G and anti-vaccination actors saw the messages of both crowds intertwine.

“The 5G stuff was already around by last year, but it latched on to COVID very early in the year and it allowed the anti-vaccine crowd an opportunity to adapt the message,” he said.

“We were seeing a lot of bad actors spreading content which basically said, you know, COVID was a plot to keep people in their homes while 5G was erected and that a COVID vaccine would contain a chip that would somehow be controlled by the 5G network, which would be part of the one-world UN agenda,” he said.

Trute said the vast bulk of Australian conspiracy material was imported directly from the US, the UK and Europe. A persistent and baseless claim that last summer’s bushfires had been orchestrated to clear land for a high-speed rail line as part of Agenda 21, had been imported directly from California, where it had surfaced two years earlier.

Last year, a government member of parliament (MP) installed security cameras at her home because she feared being physically attacked in her home after a conspiracy theorist accused her, baselessly, of being “a member of a secretive pedophile network.”

That threat came from a misguided theory that alleged Australia was controlled by a group of Freemasons.

The theory’s central tenets aligned with QAnon without specifically referring to its lore.

Joshua Roose, a senior research fellow at Deakin University, said that one of the reasons QAnon has proven to be so “magnetic” is how universal its themes are.

“Q in the Australian context is really amorphous, so when you talk about Q you’re more talking about an affiliation. You’re talking about someone identifying with something that is anti-establishment, a lack of trust in institutions and politicians, and with something that claims to be seeking the truth and fighting for good in the world,” he said.

“Conspiracy theories have been around for hundreds of years, and really you’ve got to look at the conditions that give birth to them,” he said.

“We’re in a period of extreme lack of trust in politicians, of economic downturn and of polarization. It’s in that context that people can come along and make these grandiose claims, and find traction because people are looking for something to believe and for something to belong to,” he said.

That elasticity might prove to be a telling indicator for QAnon’s future. Although much has been made of a crisis among its followers after Biden’s inauguration, Roose warned that the conditions underpinning it have not been addressed.

“The big point here is this has all happened in the decade post the global financial crisis, and I think we’ve seen the impacts of that weren’t always immediate. Five or six years after the GFC [global financial crisis], globally you’ve seen the rise of far-right populist movements in not just the US with Trump, but Brexit, Australia, Poland, Hungary, Italy, India, the Philippines and Brazil,” Roose said.

“We’ve just undergone the biggest economic hit in close to a century. These issues are not going to go away, they’re only going to get bigger. We’re at a really critical juncture in our democracy and if governments don’t reach out and engage people, and put more effort into social cohesion, we will see lots more polarization to come,” he said.

INSIDE GOVERNMENT

The presence of two government MPs in the ranks of those willing to openly and persistently propagate conspiracy theories, and their attendant popularity on social media, is probably the most blatant evidence that Australia is not immune to the great unraveling that has permeated the US.

Morrison, for months, repeatedly refused to publicly rebuke Australian MP Craig Kelly for the constant stream of misinformation about COVID-19 treatments that he has spent the past year peddling. Nor did he or his senior Cabinet colleagues offer any public criticism of fellow Coalition MP George Christensen after he parroted Trump’s baseless claims about election fraud in the US.

However, Kelly and Christensen are not alone —indeed, there is no shortage of examples to demonstrate the enthusiastic adoption of those same forces by mainstream political figures in Australia.

Four years after George lost his election bid, the Liberal Party preselected the pastor and lawyer Andrea Tokaji to run in the same seat of Baldivis.

Last month, Tokaji was forced to quit as the party’s candidate after it was revealed she wrote an article on the conservative Web site Cauldron Pool that suggested the COVID-19 virus had been caused by 5G technology, and claimed that during pandemic lockdowns “5G towers are being rolled out, against our knowledge.”

The creep of conspiratorial thinking during the pandemic has not apparently been restricted to the political right. What people on both ends of the left-right spectrum have in common is “a distrust in ‘the system’ and a desire to replace it with something that better reflects their values,” Roose said.

In December, in the northern New South Wales town of Mullumbimby — famous for its alternative lifestyle — a left-wing group called Turning Point Talks hosted a speaker who uses the name Max Igan at the town’s Politics in the Pub.

Igan — whose Web site says this is a nom de plume — is a longtime conspiracist banned from YouTube who claims, variously, that Biden is a pedophile, Hillary Rodham Clinton engages in child trafficking, and that COVID-19 is a “fraud” orchestrated to institute one world government and install “new operating systems” into people through the rollout of vaccines.

BEYOND QANON

People like Igan and George might be an example of the persistence of the ideas underpinning QAnon, if not the theory itself. Igan is not a QAnon adherent — in fact, he has described it as a “psyop.”

Yet the language and preoccupations of both men closely mirror those of QAnon, and point to the possibility that the ideas central to it could persist far beyond its shelf life as the conspiracy du jour.

Roose said Australia needs to be alert to the extent that misinformation and conspiracy theories are spreading out of sight.

“The danger is that these things become normative and people start integrating them uncritically into normal conversations. If you think back 10 years ago, some of the things that are in mainstream discourse now are just mind-blowing — and that’s the real danger, because it subverts not so much truth, but fact and evidence-based policymaking,” he said.

“These issues are not going to go away, they’re only going to get bigger. We’re at a really critical juncture in our democracy and if governments don’t reach out and engage people, and put more effort into social cohesion and developing trust in institutions, we will see lots more to come,” Roose said.

US$18.278 billion is a simple dollar figure; one that’s illustrative of the first Trump administration’s defense commitment to Taiwan. But what does Donald Trump care for money? During President Trump’s first term, the US defense department approved gross sales of “defense articles and services” to Taiwan of over US$18 billion. In September, the US-Taiwan Business Council compared Trump’s figure to the other four presidential administrations since 1993: President Clinton approved a total of US$8.702 billion from 1993 through 2000. President George W. Bush approved US$15.614 billion in eight years. This total would have been significantly greater had Taiwan’s Kuomintang-controlled Legislative Yuan been cooperative. During

Former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) in recent days was the focus of the media due to his role in arranging a Chinese “student” group to visit Taiwan. While his team defends the visit as friendly, civilized and apolitical, the general impression is that it was a political stunt orchestrated as part of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) propaganda, as its members were mainly young communists or university graduates who speak of a future of a unified country. While Ma lived in Taiwan almost his entire life — except during his early childhood in Hong Kong and student years in the US —

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on Monday unilaterally passed a preliminary review of proposed amendments to the Public Officers Election and Recall Act (公職人員選罷法) in just one minute, while Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) legislators, government officials and the media were locked out. The hasty and discourteous move — the doors of the Internal Administration Committee chamber were locked and sealed with plastic wrap before the preliminary review meeting began — was a great setback for Taiwan’s democracy. Without any legislative discussion or public witnesses, KMT Legislator Hsu Hsin-ying (徐欣瑩), the committee’s convener, began the meeting at 9am and announced passage of the

In response to a failure to understand the “good intentions” behind the use of the term “motherland,” a professor from China’s Fudan University recklessly claimed that Taiwan used to be a colony, so all it needs is a “good beating.” Such logic is risible. The Central Plains people in China were once colonized by the Mongolians, the Manchus and other foreign peoples — does that mean they also deserve a “good beating?” According to the professor, having been ruled by the Cheng Dynasty — named after its founder, Ming-loyalist Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga) — as the Kingdom of Tungning,