Climate change is bringing rising sea levels and increased flooding to some cities around the world, and drought and water shortages to others. For the 11 million inhabitants of Chennai, India, it is both.

The country’s sixth-largest city gets an average of about 1,400mm of rainfall a year, more than twice the amount that falls on London and almost four times the level of Los Angeles.

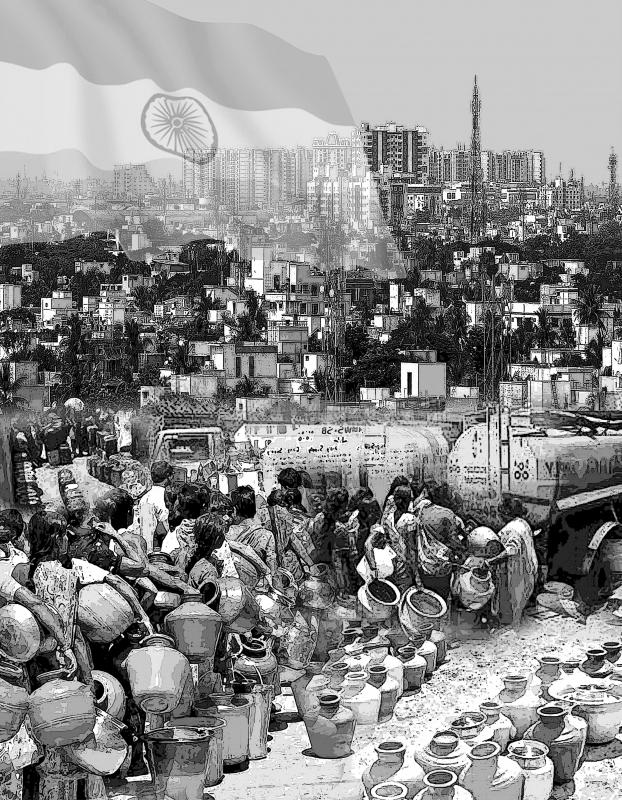

Yet in 2019, Chennai hit the headlines for being one of the first major cities in the world to run out of water — trucking in 10 million liters a day to hydrate its population.

Illustration: Constance Chou

This year, it had the wettest January in decades.

The ancient south Indian port has become a case study in what can go wrong when industrialization, urbanization and extreme weather converge, and a booming metropolis paves over its floodplain to satisfy demand for new homes, factories and offices.

Formerly called Madras, Chennai sits on a low plain on the southeast coast of India, intersected by three main rivers, all heavily polluted, that drain into the Bay of Bengal. For centuries, it has been a trading link connecting the near and far east and a gateway to south India.

Its success spawned a conurbation that grew with scant planning and now houses more people than Paris, many of them engaged in thriving automobile, healthcare, information technology (IT) and film industries.

However, its geography is also its weakness.

The cyclone-prone waters of the Bay of Bengal periodically surge into the city, forcing back the sewage-filled rivers to overflow into the streets. Rainfall is uneven, with up to 90 percent falling during the northeast monsoon season in November and December.

When rains fail, the city must rely on huge desalination plants and water piped in from hundreds of kilometers away, because most of its rivers and lakes are too polluted.

While climate change and extreme weather have played a part, the main culprit for Chennai’s water woes is poor planning.

As the city grew, vast areas of the surrounding floodplain, along with its lakes and ponds, disappeared. Between 1893 and 2017, the area of Chennai’s water bodies shrank from 12.6km2 to about 3.2km2, researchers at Chennai’s Anna University say.

Most of that loss was in the past few decades, including the construction of the city’s famous IT corridor in 2008 on about 230km2 of marshland.

The team from Anna University projects that by 2030, around 60 percent of the city’s groundwater would be critically degraded.

With fewer places to hold precipitation, flooding increased.

In 2015, Chennai experienced its worst inundation in a century.

The northeast monsoon dumped as much as 494mm of rain on the city in a single day. More than 400 people in Tamil Nadu state, of which Chennai is the capital, were killed, and 1.8 million were flooded out of their homes. In the IT corridor, water reached the second floor of some buildings.

Four years later it was a shortage of water that made headlines. The city hit what it called “day zero” as all its main reservoirs ran dry, forcing the city government to truck in drinking water. People stood in lines for hours to fill containers, water tankers were hijacked, and violence erupted in some neighborhoods.

“Floods and water scarcity have the same roots: urbanization and construction in an area, mindless of the place’s natural limits,” said Nityanand Jayaraman, a writer and environmental activist who lives in Chennai. “The two most powerful agents of change — politics and business — have visions that are too short-sighted. Unless that changes, we are doomed.”

The Tamil Nadu government predicts in its climate change action plan that the average annual temperature would rise 3.1°C by 2100 from 1970 to 2000 levels, while annual rainfall would fall by as much as 9 percent.

Worse still, precipitation during the June to September southwest monsoon, which typically brings the steady rain needed to grow crops and refill reservoirs, would reduce, while the flood-prone cyclone season in the winter would become more intense. That could mean worse floods and droughts.

The northeast monsoon officially ends in December, but this winter, the heavy rain continued well into January, with Tamil Nadu receiving more than 10 times the normal rainfall for the month.

“Such heavy rainfall was not normal when my parents and grandparents were young,” said Arun Krishnamurthy, founder of Chennai-based nonprofit organization Environmentalist Foundation of India. “People here talk a lot about the weird weather, but they don’t link it to climate change.”

Chennai is an extreme example of a problem that is increasingly disrupting cities around the world that are also grappling with rapid population increases. Beijing, Cairo and Jakarta are among urban centers facing severe water scarcity.

“It’s a global problem, not just Chennai,” Krishnamurthy said. “We need to work together to ensure that we have a water-secure future.”

The state government says that it is addressing the problem. In 2003, it passed a law requiring all buildings to harvest rainwater.

The rule helped raise the water table, but the gains were soon eroded by a lack of maintenance, the Tamil Nadu Central Ground Water Board says.

Efforts to recharge groundwater have also struggled to offset the volume of water being extracted through boreholes.

The Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board and the Tamil Nadu Water Supply and Drainage Board did not respond to questions about the issue.

Shortly after 2019’s day zero, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Edappadi Palaniswami announced a public program that would include a “massive participation of women” covering everything from rainwater harvesting, water saving, and the recycling and protection of water resources, along with studies on how to clean up the state’s polluted rivers.

Until then, the state government’s strategy had centered around the construction of large desalination plants, a costly tactic more commonly associated with arid nations or islands with limited fresh water. The plants have been criticized for causing environmental damage and having a negative impact on local fisheries.

However, the Chennai government is pursuing a new approach inspired by the city’s past.

The Greater Chennai Corp is supporting an initiative called City of 1,000 Tanks, a reference to ancient artificial lakes that were built around temples.

Supported by the Dutch government and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the plan is to restore some temple tanks and build hundreds of new ones with green slopes throughout the city to absorb and filter heavy rains, recharge the groundwater, and store water for use during dry months.

“Floods, drought and sanitation are all interlinked,” said Sudheendra N.K., director of Madras Terrace Architectural Works, which is involved in the project. “When a critical mass of people take up all this, then a significant difference will be noticed and we will no longer be in crisis.”

He said it would take at least five years for the project to have an effect.

Meanwhile, Chennai continues to add about 250,000 people per year, making it a race against time to curb the floods and water shortages.

“My fear is these things will happen more often in the future,” Krishnamurthy said. “We didn’t learn the lesson from day zero.”

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural

Former minister of culture Lung Ying-tai (龍應台) has long wielded influence through the power of words. Her articles once served as a moral compass for a society in transition. However, as her April 1 guest article in the New York Times, “The Clock Is Ticking for Taiwan,” makes all too clear, even celebrated prose can mislead when romanticism clouds political judgement. Lung crafts a narrative that is less an analysis of Taiwan’s geopolitical reality than an exercise in wistful nostalgia. As political scientists and international relations academics, we believe it is crucial to correct the misconceptions embedded in her article,

Strategic thinker Carl von Clausewitz has said that “war is politics by other means,” while investment guru Warren Buffett has said that “tariffs are an act of war.” Both aphorisms apply to China, which has long been engaged in a multifront political, economic and informational war against the US and the rest of the West. Kinetically also, China has launched the early stages of actual global conflict with its threats and aggressive moves against Taiwan, the Philippines and Japan, and its support for North Korea’s reckless actions against South Korea that could reignite the Korean War. Former US presidents Barack Obama

The pan-blue camp in the era after the rule of the two Chiangs — former presidents Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) — can be roughly divided into two main factions: the “true blue,” who insist on opposing communism to protect the Republic of China (ROC), and the “red-blue,” who completely reject the current government and would rather collude with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to control Taiwan. The families of the former group suffered brutally under the hands of communist thugs in China. They know the CPP well and harbor a deep hatred for it — the two