Iran, reeling from the effects of US sanctions, a collapse in oil sales and a severe COVID-19 epidemic, is scrambling to buy food and medicine to avoid a supply crunch, but it is a struggle.

Despite such supplies being exempt from sanctions, banks and governments are reluctant to transfer or take Iranian money because they fear unwittingly breaching the complex US restrictions, five trade and finance sources have said.

An approved trade channel launched by the Swiss government, and backed by Washington — the Swiss Humanitarian Trade Agreement (SHTA) — went live in February after more than a year of work to facilitate such Iranian purchases from Swiss companies.

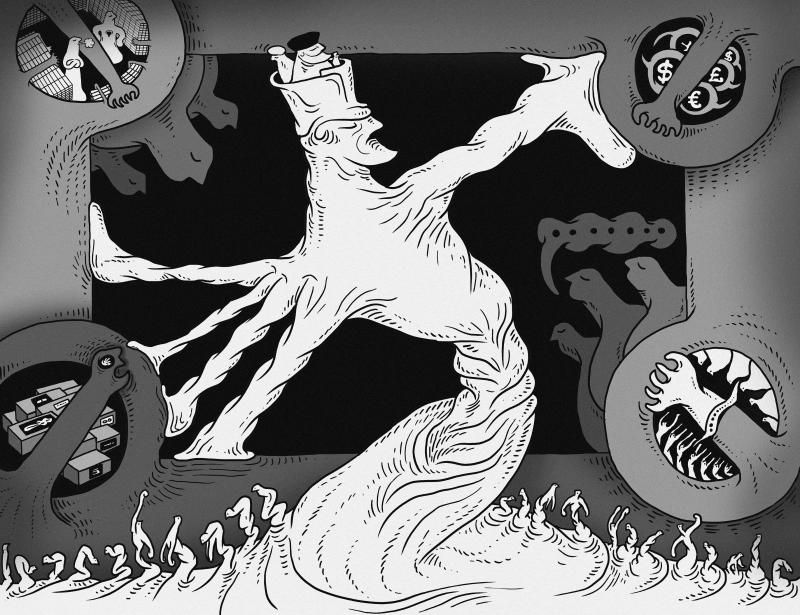

Illustration: Mountain People

Yet the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) has been unable to transfer the billions of dollars of oil export cash it had built up between 2016 and 2018 to bank accounts working with the SHTA, the five sources with knowledge of the matter said.

That money was accumulated in bank accounts in countries that Iran sold oil to — especially in Asia, with its biggest customers including South Korea and Japan — in the years after Iran signed the nuclear accord with world powers, but before US President Donald Trump’s administration withdrew and reimposed sanctions in 2018.

The funds were frozen when the sanctions, which target the CBI as well as dollar transactions with Iranian entities, were reintroduced.

As a result, international banks and their governments — whom they seek clearance from — are wary of allowing funds to be released without specific authorization from Washington for each transfer, the sources said.

The blockage illustrates how the complexity of US sanctions has made many banks, companies and countries wary of doing any business with Iran, even when exemptions exist, because breaches can involve huge financial penalties and being effectively shut out of the crucial US financial system, the sources added.

The effects have also been felt in other areas, with media previously reporting that many foreign shipping companies and insurers are unwilling to provide vessels or cover for voyages, even for commerce that has been approved.

South Korean and Japanese authorities have declined cash transfers to Switzerland by the CBI without specific US approval, said the sources, who declined to be named due to the sensitivity of the matter.

The South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirmed this.

“Under the current US sanctions, returning the money in cash is impossible,” an official said. “Any permission regarding the funds needs to be strictly authorized by the US.”

The ministry official said that Seoul had “discussed the Swiss route as another possible way of clearance [of funds],” but added that the “US hasn’t been positive about such proposals.”

It is unclear why the US might not have given specific approval for those transactions.

A Japanese Ministry of Finance official declined to comment and referred the matter to Iranian authorities.

The CBI did not respond to requests for comment.

When asked whether such transfers of funds were permitted and whether it would give specific authorizations, a US Department of the Treasury spokesperson said that the US is committed to the delivery of humanitarian goods and services to the Iranian people.

Non-US nationals can engage in the export or re-export of food, agricultural products, medicine and medical devices to Iran outside of US jurisdiction without additional authorization, provided that transactions involving the CBI are consistent with US guidance, the spokesperson added.

A US Department of State spokesperson said that the US remains committed to the success of the SHTA.

“It has never been, nor is it now, US policy to target humanitarian trade with Iran,” it added.

The Swiss government on Monday last week said that a Swiss pharmaceutical company had completed the first transaction under the new humanitarian trade channel with Iran, adding that more transactions would follow.

The SHTA needed “regular transfers of Iranian funds from abroad for its functioning,” the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) said, adding that US authorities had given assurances that they would support such transfers.

“We are in talks with the USA and other partners on this matter. However, we cannot provide information on individual transfers,” SECO said, without further details.

SECO did not comment on how the first confirmed transaction was funded.

An Iranian official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said that Tehran had been in contact with countries where it has funds to try to transfer the money under the Swiss initiative.

“These countries have approached the US to secure its approval for such a transfer, but to no avail,” the official said.

The Geneva, Switzerland-based Bangue de Commerce et de Placements (BCP) is the only financial institution that has committed to the SHTA so far and agreed to receive Iranian funds under the scheme, the sources said.

BCP did not respond to requests for comment.

The sources said that major international trading houses are ready to supply Iran with agricultural commodities under the scheme, but only when they are certain that transactions are free of any sanctions risk.

“The big trading houses will only work inside a formal US-approved payment system,” one European grain trader said.

Adding to Iran’s food-supply woes, corn imports from main supplier Brazil have slumped.

Last year, Iran was Brazil’s second-biggest buyer of corn, but in the first half of this year, imports from the country declined to about 339,000 tonnes from 2.3 million tonnes a year earlier, Brazilian government data showed.

Tehran is facing increased competition in Brazil’s corn market from other buyers, especially Taiwan.

Brazilian sellers are also struggling to find international banks willing to process the transactions because of perceived sanctions risk, seven Brazilian trade and finance sources said.

The traders have sought to use small local banks to clear Iran-related transactions, the people said.

They have also sought to use the euro to avoid dollar transactions that would be flagged to the US Treasury, they added.

Iran pays US$10 per tonne more than other buyers to compensate for payment and logistical challenges, the Brazilian trade sources said.

“Because of the hostile policies of the United States, we have to cut down imports,” said Mehdi Ansari, head of Iran-based grain trader Tejari Ansari Group.

The US Treasury declined to comment when asked about the decline in Brazilian corn sales to Iran.

Iranian buyers made about 600,000 tonnes of advanced corn purchases from Brazil last month for the second half of this year, with payments expected to be worked out once cargoes sail, trade sources said.

However, sellers could divert vessels to other buyers if Iran cannot pay.

Brazilian traders are also using barter deals — for example, taking Iranian urea to be used as fertilizer in exchange for corn, the sources said.

Carlos Millnitz, chief executive of Brazilian chemical company Eleva Quimica, said that such deals did not breach sanctions as no money was exchanged, but “make the corn more expensive for Iran.”

However, Eleva Quimica is avoiding Iranian-flagged ships for barter exchanges after two such vessels were stranded for weeks at a Brazilian port last year when state-run oil firm Petroleo Brasileiro refused to refuel them due to US sanctions, he added.

Additional reporting by Daphne Psaledakis, Tetsushi Kajimoto, Michael Shields, Michael Hogan and Karl Plume

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural