Why does the US refuse to pass new gun control laws? It is the question that people around the world keep asking.

According to Jonathan Metzl, a psychiatrist and sociologist at Vanderbilt University, white supremacy is the key to understanding the US’ gun debate.

In his new book, Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America’s Heartland, Metzl says that the intensity and polarization of the US gun debate makes much more sense when understood in the context of whiteness and white privilege.

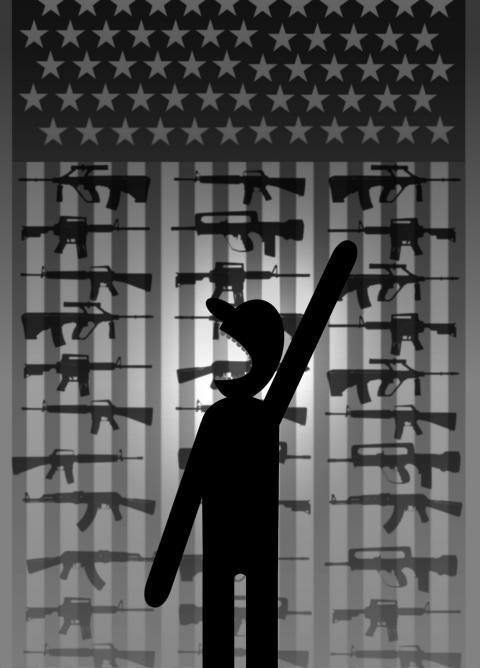

Illustration: Yusha

White Americans’ attempt to defend their status in the racial hierarchy by opposing issues such as gun control, healthcare expansion or public-school funding ends up injuring themselves, as well as hurting people of color, Metzl says.

The majority of the US’ gun death victims are white men, and most of them die from self-inflicted gunshot wounds. In all, gun suicide claims the lives of 25,000 Americans each year.

White Americans are “dying for a cause,” he writes, even if their form of death is often “slow, excruciating, and invisible.”

Metzl spoke to the Guardian about his analysis in March, and again last week, following what appeared to be a white nationalist terror attack on Latino families doing back-to-school shopping at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas that left 22 people dead.

The conversations have been condensed and edited.

You argue that the US’ debate over gun control laws and gun violence makes a lot more sense if you actually understand it as a debate over race and whiteness in the US. Why is that?

In my research I look at the history and the social meanings of how guns came to be these particularly charged social symbols. So many aspects of American gun culture are really entwined with whiteness and white privilege.

Carrying a gun in public has been coded as a white privilege. Advertisers have literally used words like “restoring your manly privilege” as a way of selling assault weapons to white men.

In colonial America, landowners could carry guns, and they bestowed that right on to poor whites to quell uprisings from “Negroes” and Indians.

John Brown’s raid was about weapons. Scholars have written about how the Ku Klux Klan was aimed at disarming African Americans.

When African Americans started to carry guns in public — think about Malcolm X during the civil rights era — all of a sudden, the second amendment didn’t apply in many white Americans’ minds.

When Huey Newton and the Black Panthers tried to arm themselves, everyone suddenly said: “We need gun control.”

When states like Missouri changed their laws to allow open carry of firearms, there were parades of white Americans who would carry big long guns through congested areas of downtown St Louis, who would go into places like Walmart and burrito restaurants carrying their guns, and they were coded as patriots.

At the same time, there were all the stories about African American gun owners who would go to Walmart and get tackled and shot.

Who gets to carry a gun in public? Who is coded as a patriot? Who is coded as a threat, or a terrorist or a gangster?

What it means to carry a gun or own a gun or buy a gun — those questions are not neutral. We have 200 years of history, or more, defining that in very racial terms.

What moments in the past few years have demonstrated to you most clearly that it is impossible to understand the US’ gun control debate without talking about whiteness?

The period after a mass shooting is often very telling. When the shooter is white, the context is the individual narrative — this individual disordered white mind. When the shooter is black or brown, all of a sudden the disorder is culture. The narrative we tell then is about terrorism or gangs.

Then there’s the quiet everyday level. There’s nothing more painful than sitting in a room with family members who have lost loved ones to suicide. I’d talk to people who had lost husbands, wives, kids, parents to gun suicide, and they would come to the interview, often, bringing their guns.

I would ask them: Did it change how you think about the gun?

They’d argue it’s never the gun’s fault and they’d need the gun in case an invader would attack them.

This narrative about protection against the radicalized invader was so profound. They were almost nervous not bringing their guns, and it was very much coded in racial terms.

A number of people I talked to in my book basically said: “I’m getting this gun because of Ferguson.”

[Ferguson is the city where the killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, by a white police officer in 2015 sparked sustained public protests led by black residents.]

These were people who lived 300 miles [483km] from Ferguson, in entirely white areas of rural America. When I tried to pin them down about it, they would say: “This could happen anywhere. I have to protect myself and my property.”

I talked to a number of people in African American communities, and for them, this meaning of guns being like a privilege was completely absent.

They had very ambiguous or mixed feelings about weapons, because, for a lot of people I spoke with in St Louis they symbolized: “Carry a gun, get shot by the police.”

Given how important you think white privilege is to understanding gun policy, should people be talking or messaging about the gun control debate differently?

I’m not imagining that MSNBC talking more about “how guns are proof that you’re racist” is going to change this debate. The point I’m making is more a diagnostic one than a prescriptive one.

I’m saying that until we understand the racial tensions that underlie the gun debate, we’re going to keep asking ourselves why this issue is so intractable.

When we talk about guns and people end up polarized, it’s not just because we disagree about gun politics, it’s because gun politics symbolizes a far greater series of tensions in this country. When we’re talking about guns, we’re also talking about race.

During a talk at a bookstore in Washington, a white nationalist group reportedly interrupted you in protest. What happened?

My dad is a Holocaust survivor and he and my grandparents escaped Nazi Austria. It took them about 10 years to get into this country and they were only allowed because of the bravery of people who stood up and vouched for them.

One of those people was in the audience, a man in his 80s who volunteered to be my father’s host.

As I was saying this, I look up to the back of the store, and there are nine men and one woman coming in with bullhorns and chanting.

They were saying things like “this land is our land” and “invaders out.”

They commandeered the talk for about five or 10 minutes. At first people thought it was a joke and then they got scared.

The bookstore is right next door to Comet Pizza, where the Pizzagate shooting happened, and then people, everyday people, stood up and shouted them down. Then they left.

It was very well rehearsed. They had a videographer there.

What connection do you see between white Americans’ daily choices about gun politics and the violent attack we saw in El Paso?

I think we run a risk of conflating all gun owners with mass shooters. I’ve gotten comments on Twitter about people being mentally ill just for wanting to own an AR-15. I don’t see those as productive.

Many of the interventions that we’re suggesting, like background checks, are going to have an impact on gun owners. It’s better off if we have a conversation with them. I think that pathologizing all gun owners gets us further away from any kind of solution that might bring people together.

At the same time, part of what I’m tracking in my research is the politics of racial resentment, a particular form of anti-immigration, anti-government, pro-gun politics that’s been represented in America for a long time.

These mass shooters, they’re not coming out of nowhere. They’re a very extreme amplification of the kinds of ideologies that are playing out in a much more quotidian way in middle America.

Did you come away from your research concluding that American gun culture is inherently toxic? Or are there other dimensions to gun ownership and gun culture?

I do think there are many positive things about gun culture. My argument is a lot more centrist than I think people realize.

It’s not just about supremacy and oppression. It’s also about history and tradition and generational meanings. I came away from this research very respectful of gun ownership traditions in many parts of the country, and things people were telling me about guns suggesting safety and protection, about the community networks that gun ownership lets people forge.

For many people living in rural America, if anything happens to them, they are far away from support systems, police and other help. I think there are plenty of rational aspects to respecting the tradition of gun ownership.

I have a lot of colleagues and interview subjects and people I’m still having conversations with who are pro-second amendment, people who don’t want mass shootings and don’t want death.

There are a lot of people who are in the middle about this on both sides, but because there’s so many actors that benefit from polarization, everyone from Twitter to the [National Rifle Association], there’s no benefit to compromising.

I can list plenty of examples where I think gun policies are not about respecting gun traditions, they’re about really pushing the envelope on seeing how far we can get.

I’m not saying that people’s guns should be taken away. I don’t agree that there should be guns in bars and college classrooms. I don’t think that people who are 18 should be carrying assault rifles.

A nation has several pillars of national defense, among them are military strength, energy and food security, and national unity. Military strength is very much on the forefront of the debate, while several recent editorials have dealt with energy security. National unity and a sense of shared purpose — especially while a powerful, hostile state is becoming increasingly menacing — are problematic, and would continue to be until the nation’s schizophrenia is properly managed. The controversy over the past few days over former navy lieutenant commander Lu Li-shih’s (呂禮詩) usage of the term “our China” during an interview about his attendance

Bo Guagua (薄瓜瓜), the son of former Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee Politburo member and former Chongqing Municipal Communist Party secretary Bo Xilai (薄熙來), used his British passport to make a low-key entry into Taiwan on a flight originating in Canada. He is set to marry the granddaughter of former political heavyweight Hsu Wen-cheng (許文政), the founder of Luodong Poh-Ai Hospital in Yilan County’s Luodong Township (羅東). Bo Xilai is a former high-ranking CCP official who was once a challenger to Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) for the chairmanship of the CCP. That makes Bo Guagua a bona fide “third-generation red”

Following the BRICS summit held in Kazan, Russia, last month, media outlets circulated familiar narratives about Russia and China’s plans to dethrone the US dollar and build a BRICS-led global order. Each summit brings renewed buzz about a BRICS cross-border payment system designed to replace the SWIFT payment system, allowing members to trade without using US dollars. Articles often highlight the appeal of this concept to BRICS members — bypassing sanctions, reducing US dollar dependence and escaping US influence. They say that, if widely adopted, the US dollar could lose its global currency status. However, none of these articles provide

US president-elect Donald Trump earlier this year accused Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) of “stealing” the US chip business. He did so to have a favorable bargaining chip in negotiations with Taiwan. During his first term from 2017 to 2021, Trump demanded that European allies increase their military budgets — especially Germany, where US troops are stationed — and that Japan and South Korea share more of the costs for stationing US troops in their countries. He demanded that rich countries not simply enjoy the “protection” the US has provided since the end of World War II, while being stingy with