In Ahmedabad, India, my driver is looking for one of the city’s in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics. We turn on to a busy main road and I spot a sign on a crumbling wall reading: “test tube babies.” I climb the filthy stairwell and enter a small, dark reception area. In the adjoining room, I spot a hospital stretcher and shelves full of metal petri dishes, forceps and hypodermic needles.

Dr Rana* leads me into a windowless office. Before we even sit down, he is telling me about a change in India’s surrogacy policy.

In October last year, the government told fertility clinics to stop all surrogate embryo transfers to foreigners. The move follows a proposed change to the law that would limit surrogacy to Indian couples, or where at least one of the commissioning parents has an Indian passport and residency.

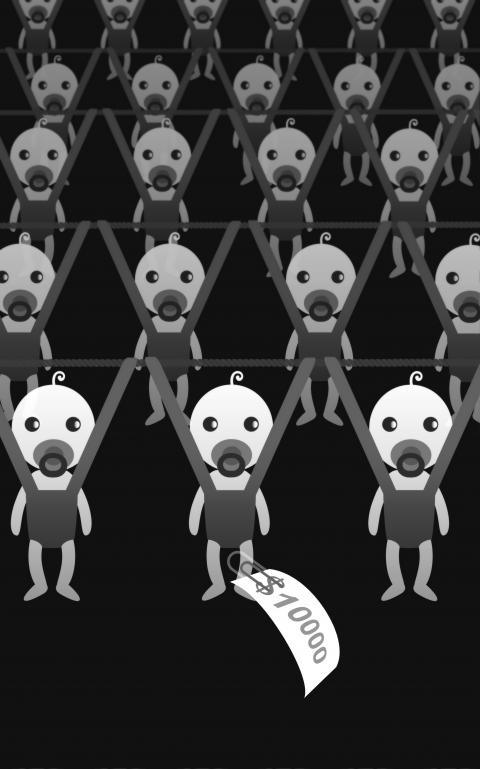

Illustration: Yusha

Having established that neither I nor the woman posing as my husband’s sister own an Indian passport, Rana advises me to go to Thailand.

“It costs twice the price [that it does] here, but they will even do sex selection, so many people will go from India,” Rana said.

Having heard many stories about how commonplace outsourcing pregnancy and reproduction is, I am in India to investigate the nation’s “rent-a-womb” industry.

As a feminist campaigner against sexual abuse of women, and in particular the sex-trade, I feel sick at the idea of wombs for rent. Sitting in the clinic, seeing smartly dressed women come in to access fertility services, all I could think about was how desperate a woman must be to carry a child for money. I know from other campaigners against womb trafficking that many surrogates are coerced by abusive husbands and pimps. Watching the smiling receptionist fill out forms on behalf of prospective commissioning parents, I could only wonder at the misery and pain experienced by the women who would end up being viewed as nothing but a vessel.

Stigma is rarely an issue for those who outsource pregnancy to poor, desperate women in India, but there is plenty leveled at surrogate mothers. Many choose to leave home during their pregnancy, as it is not seen as a respectable way to earn money, particularly if they are from rural India.

Commercial surrogacy is illegal in many nations, including the UK, France, Germany, Italy and Spain. In India, though, the industry — built on sex, race and class supremacy — is not only legal, but estimated to be worth more than £690 million (US$980 million) a year.

Surrogates are paid about £4,500 to rent their wombs at this particular clinic, a huge amount in a nation where, in 2012, average monthly earnings stood at US$215 and one-fifth of people live below the national poverty line. Clinics can make up to £18,000 from commissioning parents. The cost of bringing home a surrogate baby from India is about five times less than the sum charged in the US.

However, while surrogates are usually from poorer backgrounds, the implanted eggs are selected from women up to the age of 25, usually highly educated and screened for any hereditary illness.

All surrogates who go through these clinics are told what and when to eat and drink, and monitored to ensure they are taking their medication and maintaining their personal hygiene.

A “residential colony” is being built with money donated by several fertility clinicians to house up to 10 surrogates during the course of their pregnancy.

I decided to visit four clinics in Gujarat, one of India’s most religious states — known as the nation’s surrogacy capital — posing as a woman interested in hiring a surrogate and egg donor to gain access to those providing the services. I wanted to be able to speak from experience about the human rights abuses that result from the practice and to become more involved in the international campaign to abolish it.

I was told it is common practice to plant embryos in two or more surrogates and to perform abortions if more than one pregnancy takes hold. Similarly, if several embryos are implanted in one surrogate and a multiple pregnancy occurs, unwanted fetuses would often be aborted.

About 12,000 foreigners go to India each year to hire surrogates, many of them from the UK.

The second clinic I visit is in a quiet, suburban area of Ahmedabad, the largest city in the state.

Having spoken to the receptionist, I am introduced to an administrator, who takes my medical history. I tell her I want to access egg donation and surrogacy services, and she tells me they “do all of that.”

I ask if the surrogates live in a hostel during pregnancy, which I had seen on television back home, and she shakes her head.

I am told I can pay for a woman to be housed for nine months, “or if you want to save money, do it for a bit and then send her back home.”

In each of the clinics I visit, I ask how much the surrogates are paid.

No one would give me an exact figure, but one doctor told me that the women earn six years’ income for nine months’ work.

At 11am, on the eve of Diwali, the ancient Hindu festival of lights, one clinic is busy. Several women are applying to become surrogates; some of them, seemingly illiterate, ask the receptionist to fill in the forms for them. Others, well dressed, smiling and accompanied by their husbands, are waiting for appointments. At least 150 women accessing IVF treatment attend the clinic each month.

I am told the clinic can do nothing for me.

“Because of human rights, the government is now closing [surrogacy services]. Maybe it is because the children are not treated well,” one of the doctors said.

I had never previously heard of children born through surrogacy being harmed by commissioning parents, but there have been cases where children have been abandoned and left in India with the birth mother. In 2012, an Australian couple left behind one of the twins born to an Indian surrogate mother, reportedly because they could not afford to bring up two children.

The next morning, I am booked in for a consultation at a third clinic with Dr Mehta*. After filling in several forms, with questions about my history of infertility, I pay my 1,500 rupees (US$22.64) for a consultation.

I tell Mehta that my friend Lisa, with whom I am traveling, is of Indian origin and willing to be the official commissioning parent and then hand over the baby to me. I ask about egg donation and how I choose the donor.

“Egg donation is by an anonymous donor. You can give us preferences, such as height and hair color, but you will have to rely on us,” Mehta said. “The donor will not know to whom her eggs are given and you will not be knowing whose eggs they are. The surrogate will meet you. We will show you a catalog and you can choose the surrogate.”

All four doctors I meet in Gujarat tell me it is bad for the women to be removed from home during this period, but all were willing to arrange this. For a price.

“We can do that if you are willing, but you will have to pay for that,” Mehta said. “We do not want to separate the surrogate from her family, because if she lives from two to nine months in a separate room and environment, then it will affect her mental health.”

I have heard several stories of women being forced or coerced into surrogacy by husbands or even pimps, and ask Mehta if she is aware of this happening.

“Without the husbands’ [of the surrogates] consent we do not do surrogacy. We do not give all the money before the delivery. We take it from you, but we hand it over to her once she hands over the child to you. We give it to her in installments so she will also take care and she will deliver the baby no problem,” Mehta said.

She said they try to avoid the women forming bonds with the baby by giving them drugs to stop lactation.

“She will not produce milk at all and she will not be shown the baby,” Mehta added.

Some of the women sell their breast milk, extracted by a pump at the clinic and delivered to the commissioning parents. Others agree to be paid to directly breastfeed the baby, despite the likelihood of bonding.

The Indian Society for Assisted Reproduction is planning to challenge the Indian government on the proposed law change.

“There are millions of [US] dollars in IVF cycles,” Rana said.

At another clinic in eastern Ahmedabad, I meet Dr Amin* in a run-down building hidden between a garage and an electrical goods store. The cluttered office is windowless. Covering the walls are photographs of newborn babies and thank you cards from the commissioning parents.

Amin hands me some photographs of potential surrogates, while explaining the fees for egg donation: “Caucasian donors £2,500 to £3,000; Indian donor £1,000.”

The surrogates remain at home during their pregnancy and are monitored daily.

“I do not allow the women to live in a surrogacy house,” Amin said. “The husband is the better watchman, I feel. He is involved in the program — he knows how to take care of his woman. Outside, if she is alone, she will have many friends and [it will be] difficult for me to control. Even if I put them in a hostel, I never know what is going on there.”

I ask if the women ever experience domestic violence during pregnancy.

“Rarely, but we have seen it,” Amin said. “Last year, we heard a surrogate’s husband was beating her. She came crying to us so we put her up. After the child was born we sent her back.”

Amin said the surrogates she hires are middle class or upper class.

“Recently, we [hired] three Brahmin [a high caste] girls, all educated. We have about 25 percent of that class. About 85 percent [of all surrogates] are quite well off,” Amin said.

I suspect this is a lie. Research by pressure group Stop Surrogacy Now showed that, aside from rare cases, it is the poorest women from the lowest castes who become surrogate mothers.

We discuss the recent change in policy and Amin tells me about a surrogacy clinic in Hyderabad, India, that produced five children for a gay couple from five individual surrogates.

Same sex couples have been banned from accessing surrogacy services in India since 2013, but, as one clinician told me: “It is still going on in Delhi and elsewhere, because this is not a regulated industry.”

As we are leaving the clinic, Amin points to a photograph on the wall of a white woman holding a brown baby.

“She asked for an Indian egg donor,” Amin said.

I ask why. Does she have an Indian partner, for example?

“No, she wanted a baby with black hair,” Amin said, beaming as she takes my 1,500 rupees for the consultation fee and shows me the door.

*Names have been changed

The Chinese government on March 29 sent shock waves through the Tibetan Buddhist community by announcing the untimely death of one of its most revered spiritual figures, Hungkar Dorje Rinpoche. His sudden passing in Vietnam raised widespread suspicion and concern among his followers, who demanded an investigation. International human rights organization Human Rights Watch joined their call and urged a thorough investigation into his death, highlighting the potential involvement of the Chinese government. At just 56 years old, Rinpoche was influential not only as a spiritual leader, but also for his steadfast efforts to preserve and promote Tibetan identity and cultural

The gutting of Voice of America (VOA) and Radio Free Asia (RFA) by US President Donald Trump’s administration poses a serious threat to the global voice of freedom, particularly for those living under authoritarian regimes such as China. The US — hailed as the model of liberal democracy — has the moral responsibility to uphold the values it champions. In undermining these institutions, the US risks diminishing its “soft power,” a pivotal pillar of its global influence. VOA Tibetan and RFA Tibetan played an enormous role in promoting the strong image of the US in and outside Tibet. On VOA Tibetan,

Former minister of culture Lung Ying-tai (龍應台) has long wielded influence through the power of words. Her articles once served as a moral compass for a society in transition. However, as her April 1 guest article in the New York Times, “The Clock Is Ticking for Taiwan,” makes all too clear, even celebrated prose can mislead when romanticism clouds political judgement. Lung crafts a narrative that is less an analysis of Taiwan’s geopolitical reality than an exercise in wistful nostalgia. As political scientists and international relations academics, we believe it is crucial to correct the misconceptions embedded in her article,

Sung Chien-liang (宋建樑), the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) efforts to recall Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) Legislator Lee Kun-cheng (李坤城), caused a national outrage and drew diplomatic condemnation on Tuesday after he arrived at the New Taipei City District Prosecutors’ Office dressed in a Nazi uniform. Sung performed a Nazi salute and carried a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf as he arrived to be questioned over allegations of signature forgery in the recall petition. The KMT’s response to the incident has shown a striking lack of contrition and decency. Rather than apologizing and distancing itself from Sung’s actions,