In a cavernous production hall in Dusseldorf last fall, the somber tones of a horn player accompanied the final act of a century-old factory.

Amid the flickering of flares and torches, many of the 1,600 people losing their jobs stood stone-faced as the glowing metal of the plant’s last product — a steel pipe — was smoothed to a perfect cylinder on a rolling mill. The ceremony ended a 124-year run that began in the heyday of German industrialization and weathered two world wars, but could not survive the aftermath of the energy crisis.

There have been numerous iterations of such finales over the past year, underscoring the painful reality facing Germany: its days as an industrial superpower might be coming to an end.

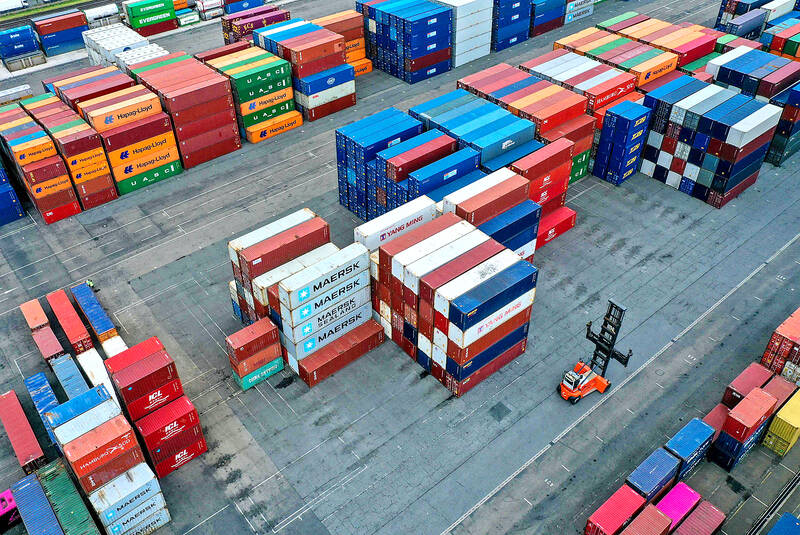

Photo: Bloomberg

Manufacturing output in Europe’s biggest economy has been trending downward since 2017, and the decline is accelerating as competitiveness erodes.

“There’s not a lot of hope, if I’m honest,” said Stefan Klebert, chief executive officer of GEA Group AG, a supplier of manufacturing machinery that traces its roots to the late 1800s. “I am really uncertain that we can halt this trend. Many things would have to change very quickly.”

The underpinnings of Germany’s industrial machine have fallen like dominoes. The US is drifting away from Europe and is seeking to compete with its transatlantic allies for climate investment. China is becoming a bigger rival and is no longer an insatiable buyer of German goods. The final blow for some heavy manufacturers was the end of huge volumes of cheap Russian natural gas.

Photo: AFP

Alongside global volatility, political paralysis in Berlin is intensifying long-standing domestic issues such as creaking infrastructure, an aging workforce and the snarl of red tape.

Germany’s education system, once a strength, is emblematic of a long-term lack of investment in public services. The Ifo research institute estimates that declining math skills will cost the economy about 14 trillion euros (US$15 trillion) in output by the end of the century.

In some cases, the industrial downshift is taking place in small steps like scaling back expansion and investment plans. Others are more evident like shifting production lines and trimming staff. In extreme instances — like Vallourec SACA’s pipe plant, once part of fallen industrial giant Mannesmann AG — the consequence is permanent closure.

Germany still has an enviable roster of small, agile manufacturers, and the Bundesbank and others reject the notion that full-blown deindustrialization is anywhere close. But with reforms stalled, it’s unclear what will slow the decline.

“We are no longer competitive,” German Minister of Finance Christian Lindner said at a Bloomberg event earlier this month. “We are getting poorer because we have no growth. We are falling behind.”

Fading industrial competitiveness threatens to plunge Germany into a downward spiral, Michelin SCA northern Europe head Maria Rottger said. The French tiremaker is shutting two of its German plants and downsizing a third by the end of next year in a move that will affect more than 1,500 workers. US rival Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co has similar plans for two facilities.

“Despite the motivation of our employees, we have arrived at a point where we can’t export truck tires from Germany at competitive prices,” she said in a recent interview. “If Germany can’t export competitively in the international context, the country loses one of its biggest strengths.”

Other examples of decline surface regularly. GEA Group is closing a pump factory near Mainz in favor of a newer site in Poland. Autoparts maker Continental AG announced plans in July last year to abandon a plant that makes components for safety and brake systems. Rival Robert Bosch GmbH is in the process of slashing thousands of workers.

The energy crisis in the summer of 2022 was a major catalyst. While worst-case scenarios like freezing homes and rationing were avoided, prices remain higher than in other economies, which adds to costs from higher wages and regulatory complexity.

Germany’s sluggish bureaucracy also is not keeping pace, even when companies are prepared to invest. GEA installed solar capacity at a factory in the western German town of Oelde, where it makes equipment that can separate cream from milk. It applied for permits to feed in the power in January last year, two months before starting construction and is still waiting for approval — nearly two years after initiating the project.

Furthermore, China is now causing trouble for Germany in a number of ways. On top of its strategic shift into advanced manufacturing, a slowdown of the Asian superpower’s economy is sapping demand for German goods even further. At the same time, cheap competition from China is worrying industries key for Germany’s climate transition — and not just electric cars.

Germany’s headwinds require adaptation. For EBM-Papst, a producer of fans and ventilators, the industrial crisis meant acquiring a struggling supplier. And to stay nimble, the company shifted production to components for heat pumps and data centers and away from the auto sector. It’s also looking to move some administrative tasks to eastern Europe or India.

“It’s not just energy,” EBM-Papst CEO Klaus Geisdorfer said in an interview. “It’s also staff availability in Germany, which is now very tense.”

Within a decade, the working-age population will be too small to keep the economy functioning as it does today, he added.

SELL-OFF: Investors expect tariff-driven volatility as the local boarse reopens today, while analysts say government support and solid fundamentals would steady sentiment Local investors are bracing for a sharp market downturn today as the nation’s financial markets resume trading following a two-day closure for national holidays before the weekend, with sentiment rattled by US President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariff announcement. Trump’s unveiling of new “reciprocal tariffs” on Wednesday triggered a sell-off in global markets, with the FTSE Taiwan Index Futures — a benchmark for Taiwanese equities traded in Singapore — tumbling 9.2 percent over the past two sessions. Meanwhile, the American depositary receipts (ADRs) of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), the most heavily weighted stock on the TAIEX, plunged 13.8 percent in

A wave of stop-loss selling and panic selling hit Taiwan's stock market at its opening today, with the weighted index plunging 2,086 points — a drop of more than 9.7 percent — marking the largest intraday point and percentage loss on record. The index bottomed out at 19,212.02, while futures were locked limit-down, with more than 1,000 stocks hitting their daily drop limit. Three heavyweight stocks — Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (Foxconn, 鴻海精密) and MediaTek (聯發科) — hit their limit-down prices as soon as the market opened, falling to NT$848 (US$25.54), NT$138.5 and NT$1,295 respectively. TSMC's

ASML Holding NV, the sole producer of the most advanced machines used in semiconductor manufacturing, said geopolitical tensions are harming innovation a day after US President Donald Trump levied massive tariffs that promise to disrupt trade flows across the entire world. “Our industry has been built basically on the ability of people to work together, to innovate together,” ASML chief executive officer Christophe Fouquet said in a recorded message at a Thursday industry event in the Netherlands. Export controls and increasing geopolitical tensions challenge that collaboration, he said, without specifically addressing the new US tariffs. Tech executives in the EU, which is

In a small town in Paraguay, a showdown is brewing between traditional producers of yerba mate, a bitter herbal tea popular across South America, and miners of a shinier treasure: gold. A rush for the precious metal is pitting mate growers and indigenous groups against the expanding operations of small-scale miners who, until recently, were their neighbors, not nemeses. “They [the miners] have destroyed everything... The canals, springs, swamps,” said Vidal Britez, president of the Yerba Mate Producers’ Association of the town of Paso Yobai, about 210km east of capital Asuncion. “You can see the pollution from the dead fish.