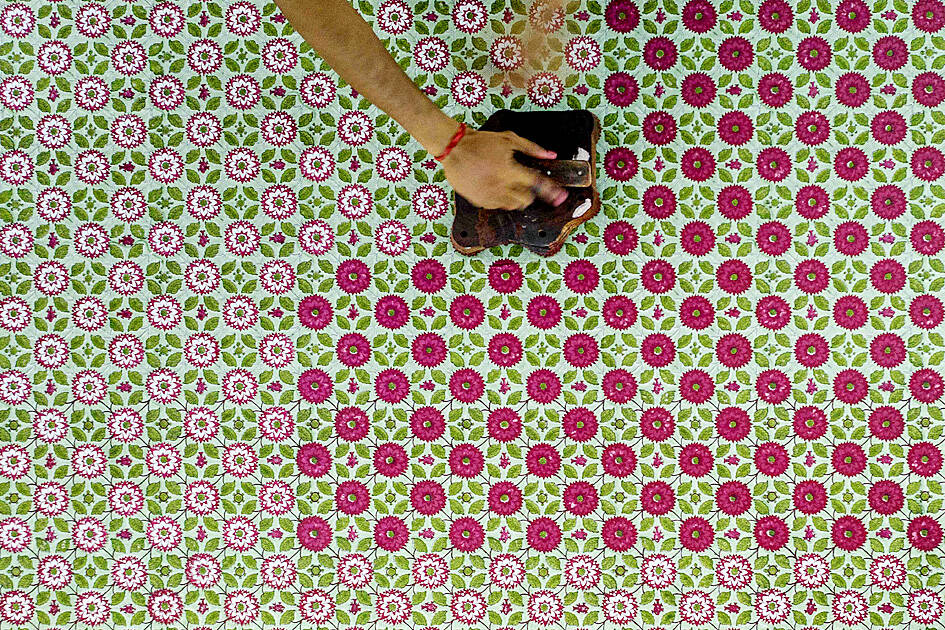

Textiles designer Brigitte Singh lovingly lays out a piece of cloth embossed with a red poppy plant she said was probably designed for Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, builder of the Taj Mahal, four centuries ago.

For Singh — who moved from France to India 42 years ago and married into a maharaja’s family — this exquisite piece remains the ever-inspiring heart of her studio’s mission.

The 67-year-old is striving to keep alive the art of block printing, which flourished in the 16th and 17th centuries under the conquering, but sophisticated, Mughal dynasty that then ruled India.

Photo: AFP

“I was the first to give a renaissance to this kind of Mughal design,” Singh said in her traditional printing workshop in Rajasthan.

Having studied decorative arts in Paris, Singh arrived aged 25 in 1980 in western India’s Jaipur, the “last bastion” of the technique of using carved blocks of wood to print patterns on material.

“I dreamed of practicing [miniature art] in Isfahan, but the Ayatollahs had just arrived in Iran [in the Islamic revolution of 1979]. Or Herat, but the Soviets had just arrived in Afghanistan,” she said.

Photo: AFP

“So by default, I ended up in Jaipur,” she said.

A few months after arriving, Singh was introduced to a member of the local nobility who was related to the maharaja of Rajasthan. They married in 1982.

At first, Singh still hoped to try her hand at miniature painting, but after scouring the city for traditional paper to work on, she came across workshops using block printing.

Photo: AFP

“I fell into the magic potion and could never go back,” she said. She started by making just a few scarves, and when she passed through London two years later, gave them as presents to friends who were connoisseurs of Indian textiles. Bowled over, they persuaded her to show them to Colefax and Fowler, the storied British interior decorations firm.

“The next thing I knew, I was on my way back to India with an order for printed textiles,” she said.

For the next two decades, she worked with a “family of printers” in the city before building her own studio in nearby Amber — a stone’s throw from Jaipur’s famous fort.

It was her father-in-law, a major collector of Rajasthan miniatures, who gave her the Mughal-era poppy cloth connected to Shah Jahan.

Her reproduction of that print was a huge success the world over, proving especially popular with Indian, British and Japanese clients.

In 2014, she made a Mughal poppy print quilted coat, called an atamsukh — meaning “comfort of the soul” — that was later acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Another piece of her work is in the collection of the Metropolitan Art Museum in New York.

Singh starts her creative process by handing precise paintings to her sculptor, Rajesh Kumar, who then painstakingly chisels the designs onto blocks of wood.

“We need a remarkable sculptor, with a very serious eye,” she said. “The carving of the wood blocks is the key. This tool has the sophistication of simplicity.”

Kumar makes several identical blocks for each color used in each printed fabric.

“The poppy motif, for example, has five colors. I had to make five blocks,” he said. “It took me 20 days.”

At Singh’s workshop, six employees work on pieces of cloth laid out on tables 5m long.

They dip the blocks in dye, place them carefully on the cloth, push down and tap.

The work is slow and intricate, producing no more than 40m of material every day.

Her workshop makes everything from quilts to curtains and rag dolls to shoes.

Singh just finished another atamsukh for a prince in Kuwait.

“The important thing is to keep the know-how alive,” she said. “More precious than the product, the real treasure is the savoir faire.”

CHIP RACE: Three years of overbroad export controls drove foreign competitors to pursue their own AI chips, and ‘cost US taxpayers billions of dollars,’ Nvidia said China has figured out the US strategy for allowing it to buy Nvidia Corp’s H200s and is rejecting the artificial intelligence (AI) chip in favor of domestically developed semiconductors, White House AI adviser David Sacks said, citing news reports. US President Donald Trump on Monday said that he would allow shipments of Nvidia’s H200 chips to China, part of an administration effort backed by Sacks to challenge Chinese tech champions such as Huawei Technologies Co (華為) by bringing US competition to their home market. On Friday, Sacks signaled that he was uncertain about whether that approach would work. “They’re rejecting our chips,” Sacks

Taiwan’s exports soared 56 percent year-on-year to an all-time high of US$64.05 billion last month, propelled by surging global demand for artificial intelligence (AI), high-performance computing and cloud service infrastructure, the Ministry of Finance said yesterday. Department of Statistics Director-General Beatrice Tsai (蔡美娜) called the figure an unexpected upside surprise, citing a wave of technology orders from overseas customers alongside the usual year-end shopping season for technology products. Growth is likely to remain strong this month, she said, projecting a 40 percent to 45 percent expansion on an annual basis. The outperformance could prompt the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and

NATIONAL SECURITY: Intel’s testing of ACM tools despite US government control ‘highlights egregious gaps in US technology protection policies,’ a former official said Chipmaker Intel Corp has tested chipmaking tools this year from a toolmaker with deep roots in China and two overseas units that were targeted by US sanctions, according to two sources with direct knowledge of the matter. Intel, which fended off calls for its CEO’s resignation from US President Donald Trump in August over his alleged ties to China, got the tools from ACM Research Inc, a Fremont, California-based producer of chipmaking equipment. Two of ACM’s units, based in Shanghai and South Korea, were among a number of firms barred last year from receiving US technology over claims they have

BARRIERS: Gudeng’s chairman said it was unlikely that the US could replicate Taiwan’s science parks in Arizona, given its strict immigration policies and cultural differences Gudeng Precision Industrial Co (家登), which supplies wafer pods to the world’s major semiconductor firms, yesterday said it is in no rush to set up production in the US due to high costs. The company supplies its customers through a warehouse in Arizona jointly operated by TSS Holdings Ltd (德鑫控股), a joint holding of Gudeng and 17 Taiwanese firms in the semiconductor supply chain, including specialty plastic compounds producer Nytex Composites Co (耐特) and automated material handling system supplier Symtek Automation Asia Co (迅得). While the company has long been exploring the feasibility of setting up production in the US to address