A villain is emerging in China’s efforts to rein in its energy prices: inefficient, power-hungry industry.

With flooding in the coal hub of Shanxi Province driving prices up to 1,508 yuan (US$234) a metric tonne even as the government tries to kick-start extra production, further measures are clearly needed to prevent more generators cutting off their turbines and causing blackouts through the cold of northern China’s winter. That means a crackdown on the factories that still consume the lion’s share of electricity.

Industry makes up only 25 percent of grid demand in the US, but in China it is fully 59 percent of the total — more than all the country’s homes, offices and retail stores put together.

Photo: EPA-EFE

Cheap power has been an essential tool of development, and the government has traditionally encouraged major users with electricity tariffs that get cheaper the more you consume. With about two-thirds of the grid powered by coal, the cost of digging up the black stuff has determined how much industrial users pay for their power.

The problem is that coal is not getting any cheaper. After a sustained period of deflation prior to 2016, when a glut of dangerous and unregulated mines was closed down, annualized costs jumped 40 percent in 2017. They did not really fall again until COVID-19 struck, and they have since rebounded with a 57 percent increase from 12 months earlier in August.

Such increases might be tolerable if end-users were turning this power into high-value goods — but all too often, that is not the case. China consumes more electricity per capita than the UK and Italy, but comes nowhere close in terms of economic output.

Determined to hit Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) targets on peaking emissions by 2030 and hitting net zero by 2060, Beijing’s policy makers have fixed on so-called “dual high” sectors — those whose energy consumption and carbon emissions are both elevated — as the culprits.

These are many of the industries that have grown fastest in the past few decades, such as cement, steel, base metals, oil refining, chemicals and glass. They collectively account for more than half of China’s emissions.

Under revised rules issued by the economic planners at the Chinese National Development and Reform Commission this week, residential and agricultural consumers would still buy power at fixed tariffs and smaller users would see electricity costs fluctuate within a band.

“Dual-high” sectors, on the other hand, would see no guardrails on the prices they pay. As a result, all the cost of balancing utilities’ books would fall on their shoulders.

This would reduce the demand pressure on the grid and encourage inefficient users to upgrade to add more value, Wan Jinsong, the commission’s director of prices, told a news conference on Tuesday.

This sounds like a neat solution — but we should not underestimate the way ripples will spread. In the past few decades, the world has become hooked on cheap Chinese power for making a host of its goods. About half of all metal is produced in China and nearly one-fifth of all oil is refined there. Energy-hungry products from aluminum to solar panels to bitcoin depend on the country’s low industrial power tariffs to keep their own prices down.

With electricity costs for dual-high industries set to rise, we might not have seen the end of the inflationary pressures flowing through the global economy from those flooded Shanxi mines.

If Beijing wants to manage this transition without crippling the economy, it is going to need to release pressure on the supply side of the energy system at the same time as taking measures to reduce demand growth.

That is where renewables come in. At the same time that price curbs are being removed from dual-high industries, so capacity curbs are being lifted from zero-carbon power generation. Provinces previously faced absolute limits on the amount of electricity they were allowed to consume, a factor that might have contributed to the most recent cuts. In the future, those bars would be removed for renewable generation, giving governors a strong incentive to switch away from constrained, inflationary coal-fired energy to unlimited, fixed-cost wind and solar.

With zero-carbon electricity already cheaper than most existing operating coal power plants, those changes might be just the spur to wean China from its addiction to solid fuel. The bulk of generation would be able to move to wind, solar, hydro and nuclear. Thermal power plants would increasingly find themselves ramping up and down to capture daily peaks in demand, with differential pricing through the day giving them the opportunity to make profits after the sun has set and when the wind drops.

All that is needed to make this system work more efficiently is for Beijing to unleash the formidable investment appetites of its provincial governments on the banquet of cheap zero-carbon power now available.

Until now, China has shied away from the sort of rapid transition that it, and the global climate, needs. The teetering state of its coal-fired power system ought to be just the catalyst to accelerate that shift.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion ofthe editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

SEMICONDUCTORS: The German laser and plasma generator company will expand its local services as its specialized offerings support Taiwan’s semiconductor industries Trumpf SE + Co KG, a global leader in supplying laser technology and plasma generators used in chip production, is expanding its investments in Taiwan in an effort to deeply integrate into the global semiconductor supply chain in the pursuit of growth. The company, headquartered in Ditzingen, Germany, has invested significantly in a newly inaugurated regional technical center for plasma generators in Taoyuan, its latest expansion in Taiwan after being engaged in various industries for more than 25 years. The center, the first of its kind Trumpf built outside Germany, aims to serve customers from Taiwan, Japan, Southeast Asia and South Korea,

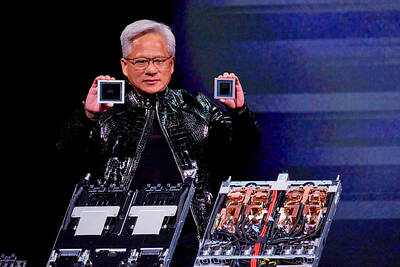

Nvidia Corp chief executive officer Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) on Monday introduced the company’s latest supercomputer platform, featuring six new chips made by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), saying that it is now “in full production.” “If Vera Rubin is going to be in time for this year, it must be in production by now, and so, today I can tell you that Vera Rubin is in full production,” Huang said during his keynote speech at CES in Las Vegas. The rollout of six concurrent chips for Vera Rubin — the company’s next-generation artificial intelligence (AI) computing platform — marks a strategic

Gasoline and diesel prices at domestic fuel stations are to fall NT$0.2 per liter this week, down for a second consecutive week, CPC Corp, Taiwan (台灣中油) and Formosa Petrochemical Corp (台塑石化) announced yesterday. Effective today, gasoline prices at CPC and Formosa stations are to drop to NT$26.4, NT$27.9 and NT$29.9 per liter for 92, 95 and 98-octane unleaded gasoline respectively, the companies said in separate statements. The price of premium diesel is to fall to NT$24.8 per liter at CPC stations and NT$24.6 at Formosa pumps, they said. The price adjustments came even as international crude oil prices rose last week, as traders

PRECEDENTED TIMES: In news that surely does not shock, AI and tech exports drove a banner for exports last year as Taiwan’s economic growth experienced a flood tide Taiwan’s exports delivered a blockbuster finish to last year with last month’s shipments rising at the second-highest pace on record as demand for artificial intelligence (AI) hardware and advanced computing remained strong, the Ministry of Finance said yesterday. Exports surged 43.4 percent from a year earlier to US$62.48 billion last month, extending growth to 26 consecutive months. Imports climbed 14.9 percent to US$43.04 billion, the second-highest monthly level historically, resulting in a trade surplus of US$19.43 billion — more than double that of the year before. Department of Statistics Director-General Beatrice Tsai (蔡美娜) described the performance as “surprisingly outstanding,” forecasting export growth