From India to China to the US, automakers cannot make vehicles — not that no one wants any, but because a more than US$450 billion industry for semiconductors got blindsided. How did both sides end up here?

Over the past two weeks, automakers across the world have bemoaned the shortage of chips. Germany’s Audi, owned by Volkswagen AG, would delay making some of its high-end vehicles because of what chief executive officer Markus Duesmann called a “massive” shortfall in an interview with the Financial Times.

The firm has furloughed more than 10,000 workers and reined in production.

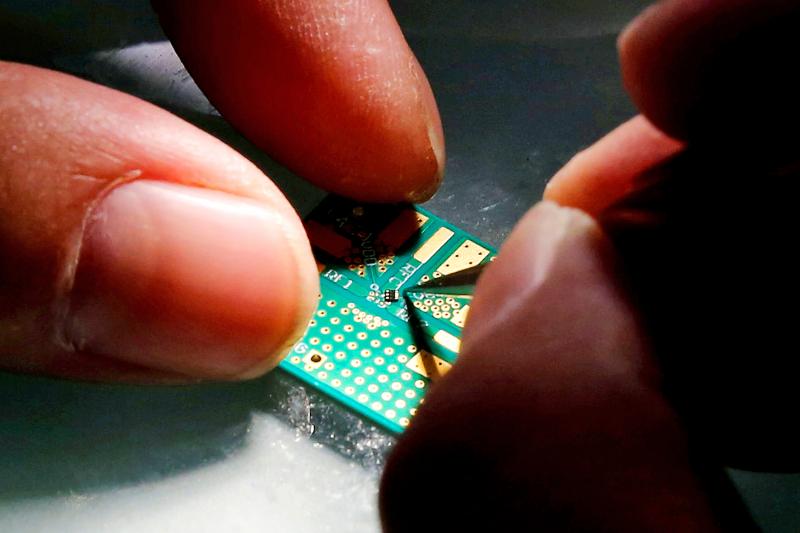

Photo: Reuters

That is a further blow to an industry reeling from COVID-19-induced shutdowns and a global market that had already been struggling under a growing regulatory push toward greener vehicles and the technology to keep up with the future of mobility.

Companies appear to have been off in their calculations that traditional auto production was all but coming to a halt, and that new-era vehicles were almost here.

In reality, talk of the death of the conventional auto industry has been premature. So were prospects around the technology upgrade that has been under way.

Yes, demand has been down and slowing, but we have been hovering around “peak auto” for a while, with global sales of 70 million to 80 million a year. They fell 15 percent to 66.8 million last year.

However, the expected onslaught of new-technology vehicles has not been as severe as the hype. Announcements of billions of dollars of investment covering electric to hydrogen and autonomous systems would have you believe that we have entered a new era of driving — or of being driven around. Yet electric and autonomous vehicles still account for only about 4 percent of all sales.

Misjudging expectations means that companies ended up effectively shelving too early their investment in the more mundane chips that help steer, brake and push up windows they actually need.

Meanwhile, chipmakers are not producing enough of them and have put money in higher-margin businesses. One result is that we are clearly at an imbalance of supply and demand.

Consider the number and types of semiconductor chips that go into a vehicle. Demand is not just about the number of automobiles, but how many chips each one needs. Electronic parts and components account for 40 percent of the cost of a new, internal-combustion engine vehicle, up from 18 percent in 2000.

That portion would continue to rise. It is becoming a problem across the board, and not just for higher-end models. India’s automakers’ association has complained of a shortage, and many vehicles there are relatively less sophisticated given pricing considerations.

So there was always going to be some sort of demand, whether you argued that more or fewer people would be driving.

Automotive electronics were expected to be the fastest-growing markets in the semiconductor industry, accounting for about 12 percent of sales revenue by next year, according to an April 2019 Deloitte report.

The 2022 model year is expected to be a key one. Credits that many automakers accumulated to meet greenhouse gas emission rules would expire at the end of the 2021 model year.

More compliant vehicles would be needed, and electrics and hybrids use twice the semiconductor content as traditional models, according to a PriceWaterhouseCoopers LLP report.

On the supply side, the concern was more around keeping up with technology. In October 2019, the likes of Samsung Electronics Co and SK Hynix Inc were contending with potential overproduction issues of certain types of chips. A year earlier, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (台積電), the world’s largest contract chipmaker, had sounded concerns about oversupply in 28-nanometer nodes — in demand for higher-end vehicle features at the time — as its other customers migrated to more advanced chipsets.

Part of the issue is that there is no fast substitute. Customers usually put orders in eight to 10 weeks ahead, but lead times have gotten much longer since the COVID-19 outbreak. Automakers in China, for instance, do not have more than a few weeks of supply on hand in keeping with lean, cost-friendly manufacturing operations.

There is also an equipment shortage, so foundries that make wafers typically suited for broad-based auto usage have limited capacity.

Chipmakers’ cycles — from development to certification — are long. Keeping track of and aligning with shifts in auto markets is difficult. The pandemic has not made that any easier. It seems that none of the players are quite in sync. The supply-demand balance is far too delicate. Even if consumer electronics are sucking up the chip supply, with everyone suddenly playing a lot more video games or increasing use of personal computers, manufacturers should not be disabled from making vehicles.

Everyone’s math ought to add up better than this.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

POWERING UP: PSUs for AI servers made up about 50% of Delta’s total server PSU revenue during the first three quarters of last year, the company said Power supply and electronic components maker Delta Electronics Inc (台達電) reported record-high revenue of NT$161.61 billion (US$5.11 billion) for last quarter and said it remains positive about this quarter. Last quarter’s figure was up 7.6 percent from the previous quarter and 41.51 percent higher than a year earlier, and largely in line with Yuanta Securities Investment Consulting Co’s (元大投顧) forecast of NT$160 billion. Delta’s annual revenue last year rose 31.76 percent year-on-year to NT$554.89 billion, also a record high for the company. Its strong performance reflected continued demand for high-performance power solutions and advanced liquid-cooling products used in artificial intelligence (AI) data centers,

SIZE MATTERS: TSMC started phasing out 8-inch wafer production last year, while Samsung is more aggressively retiring 8-inch capacity, TrendForce said Chipmakers are expected to raise prices of 8-inch wafers by up to 20 percent this year on concern over supply constraints as major contract chipmakers Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) and Samsung Electronics Co gradually retire less advanced wafer capacity, TrendForce Corp (集邦科技) said yesterday. It is the first significant across-the-board price hike since a global semiconductor correction in 2023, the Taipei-based market researcher said in a report. Global 8-inch wafer capacity slid 0.3 percent year-on-year last year, although 8-inch wafer prices still hovered at relatively stable levels throughout the year, TrendForce said. The downward trend is expected to continue this year,

Vincent Wei led fellow Singaporean farmers around an empty Malaysian plot, laying out plans for a greenhouse and rows of leafy vegetables. What he pitched was not just space for crops, but a lifeline for growers struggling to make ends meet in a city-state with high prices and little vacant land. The future agriculture hub is part of a joint special economic zone launched last year by the two neighbors, expected to cost US$123 million and produce 10,000 tonnes of fresh produce annually. It is attracting Singaporean farmers with promises of cheaper land, labor and energy just over the border.

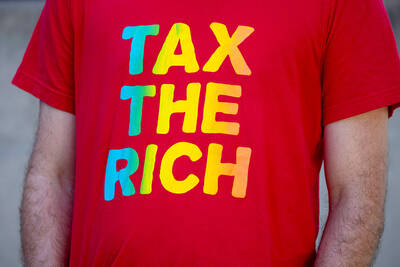

A proposed billionaires’ tax in California has ignited a political uproar in Silicon Valley, with tech titans threatening to leave the state while California Governor Gavin Newsom of the Democratic Party maneuvers to defeat a levy that he fears would lead to an exodus of wealth. A technology mecca, California has more billionaires than any other US state — a few hundred, by some estimates. About half its personal income tax revenue, a financial backbone in the nearly US$350 billion budget, comes from the top 1 percent of earners. A large healthcare union is attempting to place a proposal before