In the world’s coldest capital, many burn coal and plastic just to survive temperatures as low as minus-40°C — but warmth comes at a price: Deadly pollution makes Ulaanbataar’s air too toxic for children to breathe, leaving parents little choice but to evacuate them to the countryside.

This exodus is a stark warning of the future for urban areas in much of Asia, where scenes of citizens in anti-pollution masks against a backdrop of brown skies are becoming routine, rather than apocalyptic.

Ulaanbaatar is one of the most polluted cities on the planet, alongside New Delhi, Dhaka, Kabul, and Beijing. It regularly exceeds WHO recommendations for air quality even as experts warn of disastrous consequences, particularly for children, including stunted development, chronic illness, and in some cases, death.

Photo: AFP

Erdene-Bat Naranchimeg had to watch helplessly as her daughter Amina battled illness virtually from birth, her immune system handicapped by the smog-choked air in Mongolia’s capital.

“We would constantly be in and out of the hospital,” Naranchimeg said, adding that her child contracted pneumonia twice at the age of two, requiring several rounds of antibiotics.

This is not a unique case in a city where winter temperatures plunge toward being uninhabitable, particularly in the districts that rural workers moved to in search of a better life.

Photo: AFP

Here row upon row of the traditional tents — known as gers — are warmed by coal, or any other flammable material available. The resulting thick black smoke shoots out in plumes, blanketing surrounding areas in a film of smog that makes visibility so poor it can be hard to see even a few meters ahead.

Hospitals are packed and young children are vulnerable; common colds can quickly escalate into life-threatening illness.

The situation was so bad that doctors told Naranchimeg the only solution was to send her little girl to the clean air of the countryside.

Now aged five, she lives with her grandparents in Bornuur Sum, a village 135km away from the capital, and is thriving.

“She has not been sick since she started living here,” said Naranchimeg, who makes the three-hour round trip to see her every week.

“It was very difficult in the first few months,” she said. “We used to cry when we talked on the phone.”

However, like many parents in Ulaanbaatar, she felt the move was the only way to protect her child.

The levels of PM2.5 — fine particulate matter measuring 2.5 micrometers or smaller — in Ulaanbaatar reached 3,320 in January, 133 times what the WHO considers safe.

The effects are terrible for adults, but children are even more at risk, in part because they breathe faster, taking in more air and pollutants.

As they are smaller, children are also closer to the ground, where some pollutants concentrate, and their still-developing lungs, brains and other key organs are more vulnerable to damage.

Effects to prolonged exposure range from persistent infections and asthma to slowed lung and brain development.

The risks apply in utero, too, because gases and fine particles can enter a mother’s bloodstream and placenta, causing miscarriage, birth defects and low birth weights, which can also affect a child for the rest of their lives.

Researchers are now investigating whether pollution, like exposure to tobacco smoke, has health effects that could even be passed down to the next generation.

Buyan-Ulzii Badamkhand and her husband need to stay in capital for work, but they have decided to send their two-year-old son Temuulen more than 1,000km away.

The 35-year-old mother of three struggled with the decision, even moving from one ger district to another in the hope her son’s health would improve.

However, successive bouts of illness, including bronchitis that lasted a whole year, finally convinced Badamkhand to send her son to his grandparents.

Hours after he arrived, she called her mother-in-law to discuss her son’s medicines.

“But my mother-in-law asked me: ‘Does he still need medicine? He is not coughing anymore,’” she said.

“I tell myself that it does not matter that I miss him and who raises him, as long as he is healthy, I am content,” Badamkhand said.

Respiratory problems are the most obvious effect of air pollution, but research suggests dirty air can also put children at greater risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease later in life.

The WHO also links it to leukaemia and behavioral disorders.

When air pollution peaks in winter, Ulaanbaatar’s playgrounds empty and those who are able to are increasingly traveling abroad to wait out the smog.

In desperation, Luvsangombo Chinchuluun, a civil society activist, borrowed money to take her granddaughter to Thailand for the whole of January.

“We cannot let her play outside [in Ulaanbaatar] because of the air pollution, so we decided to leave,” she said.

The persistent smog has caused tensions in the city, with those living in wealthier areas blaming the ger residents for the pollution and even calling for the tent districts to be cleared, but the ger residents say coal is all they can afford.

“People come to the capital because they need sustainable income,” said Dorjdagva Adiyasuren, a 54-year-old mother of six.

“It’s not their fault,” she added.

In a bid to tackle the problem, the local government banned domestic migration in 2017, and a ban on burning coal comes into force from May.

However, it is unclear whether the moves will be enough to make a difference.

For Naranchimeg, the problems are serious enough to make her consider whether she wants more children.

“Now, I am terribly afraid of to give birth again. It is risky to carry a child and what will happen to the child after it is born in this amount of pollution?” she said.

‘EYE FOR AN EYE’: Two of the men were shot by a male relative of the victims, whose families turned down the opportunity to offer them amnesty, the Supreme Court said Four men were yesterday publicly executed in Afghanistan, the Supreme Court said, the highest number of executions to be carried out in one day since the Taliban’s return to power. The executions in three separate provinces brought to 10 the number of men publicly put to death since 2021, according to an Agence France-Presse tally. Public executions were common during the Taliban’s first rule from 1996 to 2001, with most of them carried out publicly in sports stadiums. Two men were shot around six or seven times by a male relative of the victims in front of spectators in Qala-i-Naw, the center

Incumbent Ecuadoran President Daniel Noboa on Sunday claimed a runaway victory in the nation’s presidential election, after voters endorsed the young leader’s “iron fist” approach to rampant cartel violence. With more than 90 percent of the votes counted, the National Election Council said Noboa had an unassailable 12-point lead over his leftist rival Luisa Gonzalez. Official results showed Noboa with 56 percent of the vote, against Gonzalez’s 44 percent — a far bigger winning margin than expected after a virtual tie in the first round. Speaking to jubilant supporters in his hometown of Olon, the 37-year-old president claimed a “historic victory.” “A huge hug

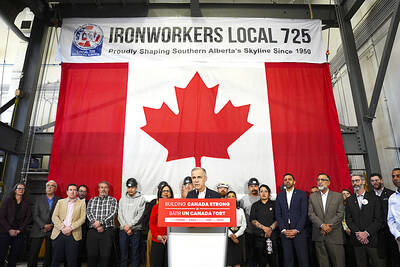

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney is leaning into his banking background as his country fights a trade war with the US, but his financial ties have also made him a target for conspiracy theories. Incorporating tropes familiar to followers of the far-right QAnon movement, conspiratorial social media posts about the Liberal leader have surged ahead of the country’s April 28 election. Posts range from false claims he recited a “satanic chant” at a campaign event to artificial intelligence (AI)-generated images of him in a pool with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. “He’s the ideal person to be targeted here, for sure, due to

DISPUTE: Beijing seeks global support against Trump’s tariffs, but many governments remain hesitant to align, including India, ASEAN countries and Australia China is reaching out to other nations as the US layers on more tariffs, in what appears to be an attempt by Beijing to form a united front to compel Washington to retreat. Days into the effort, it is meeting only partial success from countries unwilling to ally with the main target of US President Donald Trump’s trade war. Facing the cratering of global markets, Trump on Wednesday backed off his tariffs on most nations for 90 days, saying countries were lining up to negotiate more favorable conditions. China has refused to seek talks, saying the US was insincere and that it