Sleeping on a tiled classroom floor, sharing cigarettes and always on the lookout for police raids, the students of Carmela Carvajal primary and secondary school are living a revolution.

It began early one morning in May, when dozens of teenage girls emerged from the predawn darkness and scaled the spiked iron fence around Chile’s most prestigious girls’ school. They used classroom chairs to barricade themselves inside and settled in. Five months later, the occupation shows no signs of dying and the students are still fighting for their goal: free university education for all.

A tour of the school is a trip into the wired reality of a generation that boasts the communication tools that feisty young rebels of history never dreamed of. When police forces move closer, the students use restricted Facebook chat sessions to mobilize. Within minutes, they are able to rally support groups from other public schools in the neighborhood.

“Our lawyer lives over there,” said Angelica Alvarez, 14, as she pointed to a cluster of nearby homes.

“If we yell: ‘Mauricio’ really loud, he leaves his home and comes over,” she said.

For five months, the students at Carmela Carvajal have lived on the ground floor, sometimes sleeping in the gym, but usually in the abandoned classrooms where they hauled in a TV, set up a private changing room and began to experience school from a different perspective.

The first thing they did after taking over the school was to hold a vote. Approximately half of the 1,800 students participated in the polls to approve the takeover, and the yays outnumbered the nays 10 to one.

Now the students pass their school days listening to guest lecturers who provide free classes on topics ranging from economics to astronomy. Extracurricular classes include yoga and salsa lessons. At night and on weekends, visiting rock bands set up their equipment and charge 1,000 pesos (US$1.93) per person to hear a live jam on the basketball court. Neighbors donate fresh baked cakes and, under a quirk of Chilean law, the government is obliged to feed students who are at school — even students who have shut down education as usual.

So much food has poured in that the students from Carmela Carvajal now regularly pass on their donations to hungry students at other occupied schools.

Municipal authorities have repeatedly attempted to retake the school, sending in police to evict the rebel students and get classes back on schedule, but so far the youngsters have held their ground.

“It was the most beautiful -moment, all of us in [school] uniform climbing over the fence, taking back control of our school. It was such an emotional moment, we all wanted to cry,” Alvarez said. “There have been 10 times that the police have taken back the school and every time we come and take it back again.”

The students have built a hyper-organized, if somewhat legalistic, world, with votes on everything including daily duties, housekeeping schedules and the election of a president and spokeswoman. The school rules now include several new decrees: no sex, no boys and no booze. That last clause has been a bit abused, the students say.

“We have had a few cases of classmates who tried to bring in alcohol, but we caught them and they were punished,” said Alvarez, who was stationed at the school entrance questioning visitors.

Alvarez, who has lived at the school for about four months, laughed as she described the punishment.

“They had to clean the bathrooms,” she said.

Carmela Carvajal is among Chile’s most successful state schools. Nearly all the graduates are assured of a place in top Chilean universities, and the school is a magnet, drawing in some of the brightest minds from across Santiago, the nation’s capital and a metropolis of 6 million.

However, the story playing out in its classrooms is just a small part of a national student uprising that has seized control of the political agenda, wrongfooted conservative Chilean President Sebastian Pinera and called into question the free-market orthodoxy that has -dominated Chilean politics since the Pinochet era.

The students are demanding a return to the 1960s, when public university education was free. Current tuition fees average nearly three times the minimum annual wage, and with interest rates on student loans at 7 percent, the students have made financial reform the centerpiece of their uprising.

At the heart of the students’ agenda is the demand that education be recognized as a common right for all, not a “consumer good” to be sold on the open market.

The Burmese junta has said that detained former leader Aung San Suu Kyi is “in good health,” a day after her son said he has received little information about the 80-year-old’s condition and fears she could die without him knowing. In an interview in Tokyo earlier this week, Kim Aris said he had not heard from his mother in years and believes she is being held incommunicado in the capital, Naypyidaw. Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was detained after a 2021 military coup that ousted her elected civilian government and sparked a civil war. She is serving a

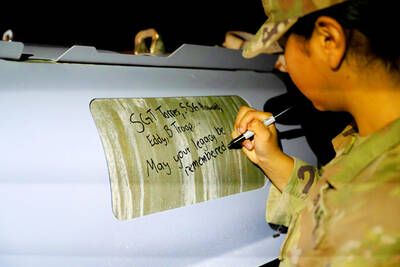

REVENGE: Trump said he had the support of the Syrian government for the strikes, which took place in response to an Islamic State attack on US soldiers last week The US launched large-scale airstrikes on more than 70 targets across Syria, the Pentagon said on Friday, fulfilling US President Donald Trump’s vow to strike back after the killing of two US soldiers. “This is not the beginning of a war — it is a declaration of vengeance,” US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth wrote on social media. “Today, we hunted and we killed our enemies. Lots of them. And we will continue.” The US Central Command said that fighter jets, attack helicopters and artillery targeted ISIS infrastructure and weapon sites. “All terrorists who are evil enough to attack Americans are hereby warned

Seven wild Asiatic elephants were killed and a calf was injured when a high-speed passenger train collided with a herd crossing the tracks in India’s northeastern state of Assam early yesterday, local authorities said. The train driver spotted the herd of about 100 elephants and used the emergency brakes, but the train still hit some of the animals, Indian Railways spokesman Kapinjal Kishore Sharma told reporters. Five train coaches and the engine derailed following the impact, but there were no human casualties, Sharma said. Veterinarians carried out autopsies on the dead elephants, which were to be buried later in the day. The accident site

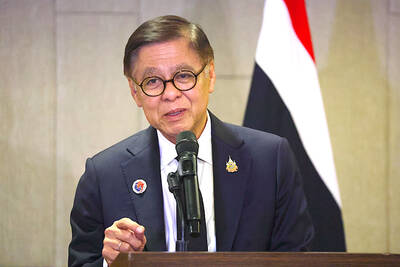

RUSHED: The US pushed for the October deal to be ready for a ceremony with Trump, but sometimes it takes time to create an agreement that can hold, a Thai official said Defense officials from Thailand and Cambodia are to meet tomorrow to discuss the possibility of resuming a ceasefire between the two countries, Thailand’s top diplomat said yesterday, as border fighting entered a third week. A ceasefire agreement in October was rushed to ensure it could be witnessed by US President Donald Trump and lacked sufficient details to ensure the deal to end the armed conflict would hold, Thai Minister of Foreign Affairs Sihasak Phuangketkeow said after an ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Kuala Lumpur. The two countries agreed to hold talks using their General Border Committee, an established bilateral mechanism, with Thailand