Liberty Times (LT): Can you tell us how you came to write the novel, The Chen Cheng-po Code (陳澄波密碼)?

Ko Tsung-ming (柯宗明): My wife, Shih Ju-fang (施如芳), and I have long worked together writing scripts, and in 2007 we were approached by [artistic director] Wang An-chi (王安祈), who asked us to create a script based on localist imagery, for a piece that would be performed by the Guoguang Opera Company.

We believed our home was our ancestral land, and everything on Taiwan should therefore be considered local. We did not believe that localist culture should be confined to the temples. I thought of Chinese calligraphist Wang Xizhi’s (王羲之, 303-361) work, Sunlight After Snowfall (快雪時晴), that was collected by the National Palace Museum. The piece of calligraphy was brought to Taiwan and has since become part of Taiwan’s culture.

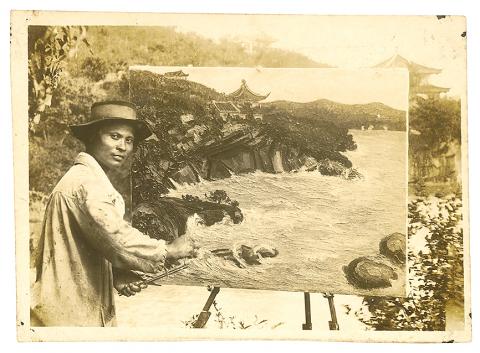

Photo: George Tsorng, Taipei Times

When Wang, along with the then-Chin Dynasty [晉朝, during the Western Chin period, 265-317], settled in [China’s] Jiangnan region (江南), he told his children that Jiangnan was their home, that they were not refugees, but had rather relocated to the region.

It is from this perspective that my wife and I came to write the script for the play that shared the same name as Wang’s calligraphy.

Chen Cheng-po’s (陳澄波) eldest grandson was quite moved when he saw the performance, and asked if it was possible to write a script for another Beijing opera play for Chen.

Photo: Tsai Shu-yuan, Taipei Times

That is how we began gathering material and researching Chen’s life.

During the research process we learned that his wife, Chang Chieh (張捷), was a great woman. After her husband was executed by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), Chang hired a photographer to take a picture of Chen after his execution, which provided proof that Chen was a victim of the 228 Massacre.

Second, Chang is a great woman, as she was able to withstand the pressure of the White Terror era and to the best of her abilities save all of Chen’s works, allowing posterity to witness his great works.

My wife wrote the script for the musical, The Woman Who Hid the Paintings (藏畫的女人), and I wrote the novel, as I had been greatly moved by Chen’s philosophy and his paintings.

LT: It is difficult not to think of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code when hearing the name of your book. In The Da Vinci Code the author’s knowledge of art helps him solve the mystery. In Chen Cheng-po’s Code, we see his personal will and the difficulties faced by his family. Can you tell us why you named the book so?

Ko: I wanted to vindicate Chen. The perception of Chen’s works in Taiwan’s art scene is varied. Although he was the first Taiwanese oil painter to have his work selected to for the Japanese Imperial Exposition, painter Hsieh Li-fa (謝里法) was of the opinion that Chen’s technique was clumsy and awkward, which Hsieh said showed that Chen had learned to paint at a very late stage and was unable to display a fluidity in technique and style.

However, I have gone through Chen’s diaries and notes, and found that Chen intentionally maintained this sense of clumsiness in his paintings. This likens Chen to Van Gogh, who sought to shake aside the regulations of academicism and pursue freedom in the expression of his own soul; or like Picasso, who despite evidential mastery of the classic techniques in his blue period paintings, adopting what seemed to be awkward technique in the creation of the painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

It is my opinion that all three painters sought to return to the basics, and Chen’s “awkward and clumsy” technique was simply seeking freedom of his inner expression.

“To rationally and explanatorily draw the depiction of an item presents no fun; no matter how well-drawn or well-painted, it lacks the force that would truly impress. The results of allowing pure feeling to guide the brush is better than that of dedicated and exhaustive work,” Chen once wrote. I included the passage in the novel to change the perception that Chen’s paintings were not “fluid” enough due to his lateness in learning how to paint.

I also tried to analyze Chen’s motivation for creation from his work. For example, his handling of space does not conform to the “golden ratio” of traditional painting techniques.

An example of this is his work Street View in Summer (夏日街景), painted in 1927. In the painting, the “plaza” comprises more than half of the painting — a sight that is oft-seen in his other works. I think that Chen did so intentionally and I have strongly emphasized the importance of the “plaza theory” in the Pro Art school in the novel.

I am of the opinion that Chen created such a large “plaza” to allow space to support and sustain the people who live on the land. These individuals are the people Chen are concerned about, and in such a manner, Chen has demonstrated his adherence to, or belief in, the spirit of humanism.

LT: Which of Chen’s paintings did you analyze when writing the book?

Ko: The foundation gave my wife and me access to many primary source documents when we were working on The Women Who Hid the Paintings.

I had previously worked on a documentary on Taiwanese art history, so I had some knowledge of the period’s artists and the historical context of their creative endeavors. This enabled me to work Chen’s art into the novel. Each segment of the story has a painting as a piece of supporting evidence, which helps readers understand concepts that words cannot adequately describe.

In a sense, the paintings are cinematic explainers of the drama and enlivens the characters. After the novel, readers who revisit Chen’s paintings would have a better sense of what Chen’s life and time was like.

My Family (我的家庭) is the most dramatic of Chen’s paintings. The use of the word jiating [家庭, singular collective of family] rather than jiaren [家人, family members] for the painting’s name is a meaningful choice.

Also highly unusual is Chen’s decision to paint each of his family members in a different garb that represented Han Chinese and Aboriginal ethnicities. Mainly, this painting is interesting for the fact that it contains the “code” for Chen’s most deeply held beliefs.

In 1979, when Chen’s family opened an exhibit of his works, they omitted this painting from the physical collection, but listed it in the catalog. As I inspected the catalog, I found the image of the painting showed a book with a blank cover.

However, in the actual painting the cover bears the title On Proletarian Painting (普羅繪畫論). After discussing this with Chen’s family, I found that the book is a major work of Japanese leftist thinker Isshu Nagata, which proves Chen was deeply influenced by left-wing thought.

In the White Terror era, having any association with the left was dangerous, so the Chen family did not dare to publicly display this painting and censored the book’s title from the image of the painting in the catalog.

Once you crack the code, you can see the dark shadows lurking during that period.

LT: What was the most challenging aspect of writing the book?

Ko: Any novelist of historical fiction knows that drawing the boundary between reality and fiction is subtle work. Many of the events in my novel are fictional; for instance, contents of many of the dialogues Chen had with famous painters of the time, such as Lin Yu-shan (林玉山) and Yang San-lang (楊三郎).

I wrote these fictional dialogues by imagining what could have transpired. Although these people have long since passed away, the imaginary reconstructions must be handled responsibly and respectfully, without causing offense to their descendants.

When writing these parts, I followed certain rules. Although the dialogues and scenarios are fictional, they have to be based on some facts that would at the very least make them plausible.

Historical fiction is fictional. It has to have a decree of historical authenticity, but an overly timid writer risks losing the drama of the story. This is the biggest challenge for writers of historical fiction.

LT: What is the facet of Chen that you most want to present in your book?

Ko: I think most readers know little of Chen except that he died in the 228 Incident. They are probably even less familiar with the tribulations an artist like Chen would have suffered during the late Japanese colonial era to the post-war period.

I would like the readers to experience the world as Chen did. The Chen in my book is neither a hero nor a victim. He was a living soul with hesitations, struggles and even contradictions.

However, Chen walked his own path and did what felt right to him at a dangerous time. Like [Qing Dynasty-era revolutionary] Chiu Chin (秋瑾), who knew being a revolutionary might cost her life, Chen died to stay true to his passion for humanity and the world.

Translated by staff writers Jake Chung and Jonathan Chin

An essay competition jointly organized by a local writing society and a publisher affiliated with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) might have contravened the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) said on Thursday. “In this case, the partner organization is clearly an agency under the CCP’s Fujian Provincial Committee,” MAC Deputy Minister and spokesperson Liang Wen-chieh (梁文傑) said at a news briefing in Taipei. “It also involves bringing Taiwanese students to China with all-expenses-paid arrangements to attend award ceremonies and camps,” Liang said. Those two “characteristics” are typically sufficient

A magnitude 5.9 earthquake that struck about 33km off the coast of Hualien City was the "main shock" in a series of quakes in the area, with aftershocks expected over the next three days, the Central Weather Administration (CWA) said yesterday. Prior to the magnitude 5.9 quake shaking most of Taiwan at 6:53pm yesterday, six other earthquakes stronger than a magnitude of 4, starting with a magnitude 5.5 quake at 6:09pm, occurred in the area. CWA Seismological Center Director Wu Chien-fu (吳健富) confirmed that the quakes were all part of the same series and that the magnitude 5.5 temblor was

The brilliant blue waters, thick foliage and bucolic atmosphere on this seemingly idyllic archipelago deep in the Pacific Ocean belie the key role it now plays in a titanic geopolitical struggle. Palau is again on the front line as China, and the US and its allies prepare their forces in an intensifying contest for control over the Asia-Pacific region. The democratic nation of just 17,000 people hosts US-controlled airstrips and soon-to-be-completed radar installations that the US military describes as “critical” to monitoring vast swathes of water and airspace. It is also a key piece of the second island chain, a string of

The Central Weather Administration has issued a heat alert for southeastern Taiwan, warning of temperatures as high as 36°C today, while alerting some coastal areas of strong winds later in the day. Kaohsiung’s Neimen District (內門) and Pingtung County’s Neipu Township (內埔) are under an orange heat alert, which warns of temperatures as high as 36°C for three consecutive days, the CWA said, citing southwest winds. The heat would also extend to Tainan’s Nansi (楠西) and Yujing (玉井) districts, as well as Pingtung’s Gaoshu (高樹), Yanpu (鹽埔) and Majia (瑪家) townships, it said, forecasting highs of up to 36°C in those areas