When 14-year-old Johnson left his village in Zimbabwe he had one goal in mind — to reach South Africa and the World Cup. A few weeks ago he finally made it, struggling through a hole in the barbed-wire border fence, but the horrors he encountered on his journey — the beatings and robbery by armed gangs, the crocodile-infested Limpopo and the screams of girls in the darkness of the bush — will stay with him for ever.

“I had nothing at home and there was no food and I heard there was going to be plenty of work in South Africa, so I decided to come,” he said. “The crossing was very bad. I was traveling with four other children, but only two of us made it across the border.”

Clad in a faded Arsenal T-shirt, he shows wounds on his leg that he claims are from beatings by magumaguma, armed bandits who patrol the bush on either side of the border, extorting money for “safe passage” and raping and robbing with impunity.

“When we crossed the river, we came upon the bandits, who hit us with sticks and stole our money,” he said. “They chased some girls and we heard them screaming, but we ran away.”

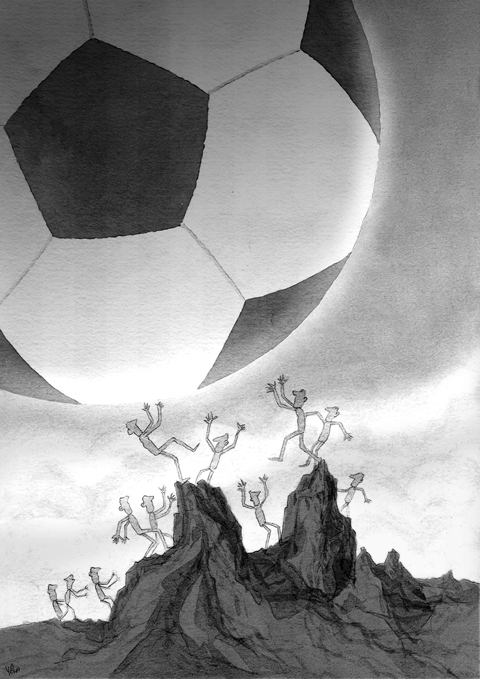

Despite the scars that bear witness to these attacks, Johnson is one of the lucky ones. Every month, some of the estimated 3,000 Zimbabwean children who attempt to make the crossing into South Africa die trying. Now, as World Cup fever sweeps through the African continent, increasing numbers of child migrants trying to move illegally across this and other borders into South Africa are risking their lives and facing robbery, rape and exploitation.

Many are drawn by the allure of the tournament and the promise of a boom in informal and largely unregulated jobs generated by the hundreds of thousands of tourists descending on the country in the coming weeks.

Others are coming simply to see the soccer.

In a soup kitchen run by Save the Children UK close to the border, 17-year-old Raphael said he had been in South Africa for six months and that he has nearly saved the money he needs to get to Johannesburg.

“We came to South Africa because of problems in Zimbabwe. There is no money and no work, but coming to see the football is one of the reasons we boys now come to South Africa,” he said. “I am certain I will be able to get a ticket for one of the games.”

“Many come to us in a bad way,” said Nemaranzhe Themba, a government social worker in Musina. “You see the numbers on the streets every night? We just can’t get to them all. The police do pick some up at the border who are naked because their clothes and everything have been stolen or they are bleeding, and much worse things happen to the girls.”

In the past week, there have been almost 50 new arrivals.

“They all want to go to Johannesburg, but most don’t even know where it is. Even those we send back, we see them here again in town just a few weeks later,” Themba said.

Until a few days ago, Cecilia, a tiny, shorn-headed 10-year-old, slept and scavenged on the streets, before she was picked up by a social worker and brought to a refuge for migrant women and girls. In a faded green dress and cracked flip-flops, she now sits in silence in a corner talking to no one.

Refuge staff think her parents died of cholera last year and since then she has fended for herself.

“We’ve seen her before, she comes backwards and forwards across the border trying to make money, but this time she had bad injuries and has obviously suffered a lot, but she still barely says a word and we don’t know what to do with her,” said Babongile Mudau, the refuge manager. “Obviously, the risk is that at some point she will just disappear, be picked up by someone or try to get to one of the cities and we will lose track of her entirely.”

Despite the dangers they face crossing and the hardships they go through trying to survive afterwards, the view of the majority of migrant children here seems to be that a life on the streets in South Africa is still infinitely better than what they have at home.

“At home there is nothing, no food. I want to go to school, but there is no possibility of this in Zimbabwe,” said Memory Gokwe, a 16-year-old from Gwanda, in the south of Zimbabwe.

Like many migrant children here in Musina, Memory paid money to a people-smuggler to secure her crossing.

“My sister sent a man, a transporter, to my village to bring me here to South Africa,” she said. “He was supposed to bring me across the border in a truck, but instead he passed me to another man who took me and four other children and two grown women through the river Limpopo to get to the border. The man wanted to rape us, but the women said they should be the ones instead of us, so when that happened we ran away.”

In February, UNICEF warned that the World Cup would bring a “flood” of child migrants into South Africa. The South African government has put patrols along the 200km barbed-wire border and promised extra shelters in tournament cities.

“When you’ve got something like the World Cup going on, it’s difficult to cope with both the increased numbers and keep the pressure on to protect the most vulnerable,” said Rudzani Ramugondo, Save the Children UK’s deputy program manager in Musina, who lists xenophobia, drug trafficking and exploitation as some of the dangers migrant children could face.

“For example, in the past weeks or months we have simply stopped seeing girls coming across the border, which doesn’t mean they’re not coming, it just means that the people-smugglers are getting better at picking them up or hiding them in containers or trucks where they are transported straight to the cities,” Ramugondo said.

On the long tarmac road out of Musina cars pass groups of children clad in tattered shorts and gym shoes, hoping to catch a lift for part of the 580km journey to Johannesburg. Those who reach the city usually end up in downtown areas like Hillbrow, where Elliot Hrutlwo, a community worker for the Johannesburg Child Welfare Group, has seen increasing numbers of children on the streets from Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Malawi in recent weeks.

“The World Cup could be great for South Africa, but bad for these children,” he said.

Hrutlwo points to a group of boys aged about 14 or 15 sitting glassy-eyed in a Hillbrow public park.

“Those boys, last week they came from Musina,” he said. “They got here and said: ‘Where are the jobs? Where are the schools?’ Already they are sniffing glue. The problem is that after the World Cup they will still be here once the world has forgotten about South Africa again and then what will happen to them?”

You wish every Taiwanese spoke English like I do. I was not born an anglophone, yet I am paid to write and speak in English. It is my working language and my primary idiom in private. I am more than bilingual: I think in English; it is my language now. Can you guess how many native English speakers I had as teachers in my entire life? Zero. I only lived in an English-speaking country, Australia, in my 30s, and it was because I was already fluent that I was able to live and pursue a career. English became my main language during adulthood

The international women’s soccer match between Taiwan and New Zealand at the Kaohsiung Nanzih Football Stadium, scheduled for Tuesday last week, was canceled at the last minute amid safety concerns over poor field conditions raised by the visiting team. The Football Ferns, as New Zealand’s women’s soccer team are known, had arrived in Taiwan one week earlier to prepare and soon raised their concerns. Efforts were made to improve the field, but the replacement patches of grass could not grow fast enough. The Football Ferns canceled the closed-door training match and then days later, the main event against Team Taiwan. The safety

There are moments in history when America has turned its back on its principles and withdrawn from past commitments in service of higher goals. For example, US-Soviet Cold War competition compelled America to make a range of deals with unsavory and undemocratic figures across Latin America and Africa in service of geostrategic aims. The United States overlooked mass atrocities against the Bengali population in modern-day Bangladesh in the early 1970s in service of its tilt toward Pakistan, a relationship the Nixon administration deemed critical to its larger aims in developing relations with China. Then, of course, America switched diplomatic recognition

The National Immigration Agency on Tuesday said it had notified some naturalized citizens from China that they still had to renounce their People’s Republic of China (PRC) citizenship. They must provide proof that they have canceled their household registration in China within three months of the receipt of the notice. If they do not, the agency said it would cancel their household registration in Taiwan. Chinese are required to give up their PRC citizenship and household registration to become Republic of China (ROC) nationals, Mainland Affairs Council Minister Chiu Chui-cheng (邱垂正) said. He was referring to Article 9-1 of the Act