In the 51 years since China took complete control of Tibet, an average of 3,000 Tibetans have crossed the Himalayas each year — each one embarking on an adventure in their quest for freedom.

Jamga, chairman of the Taiwan Tibetan Welfare Association, has not seen his family for more than 20 years — since the morning he left home for Dharamsala in India, the seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile.

“I left home early, telling my family that I was going to a nearby temple, because my mother was already over 60 years old at the time and I didn’t want her to worry about me,” Jamga told the Taipei Times. “So no one in my family knew that I was actually going to India.”

It was 1987, and Jamga was 21 years old. His family only found out what had happened five or six days after he arrived in Taiwan.

From his hometown on the Tibetan side of the border between Tibet and Sichuan Province, Jamga first crossed into Sichuan, then through Qinghai Province before finally arriving in Lhasa.

It was from Lhasa that Jamga began his three-month journey across the Himalayas into Nepal.

His life-changing journey was inspired by a chat he had with a Tibetan businessman who traveled back and forth between India and Tibet.

“When I was younger, I once traveled to Lhasa and met this Tibetan businessman who had just returned from a business trip to India,” Jamga said. “He told me how free life was in India, and how Tibetans living there could practice their religion freely, and pass on traditional Tibetan culture to their children.”

From that moment on, Jamga began to dream of escaping Tibet, which he called a place “without freedom and without religion,” and started to save his money.

“I first went to the area around the border between Tibet and Nepal by myself, and joined around a dozen other Tibetans who also wanted to go to India with a Nepali guide,” he said.

To cross the roof of the world was a challenge, and to do so without being noticed by Chinese border patrols was another.

“We’ve all heard stories of Tibetans being shot by Chinese border patrols while trying to escape, so we had to sleep during the day and walk at night, which made it very hard to see clearly, especially when it was snowing,” Jamga said. “We could not see where we were going.”

The trip was a combination of hunger, extreme weather and the threat of being shot.

“One of the members in the group died since we had nothing to eat for a few days,” he said.

Jamga said he felt relaxed when he finally reached Nepal. The group was welcomed by representatives of the Tibetan government-in-exile, and was sent to Dharamsala after resting for a few days.

“I was in Dharamsala for the first time, but I felt at home immediately,” he said.

Although Jamga has not seen his family for more than 20 years — even after he became a naturalized Taiwanese, the Chinese government would not issue him a visa — he never regretted the decision to leave home.

“I’m still glad that I escaped, living under repression is horrible,” he said.

Dawa Tsering, chairman of the Tibet Religious Foundation of His Holiness the Dalai Lama — the Tibetan government-in-exile’s de 苯actor ambassador to Taiwan — made the trip in 1992 for a very different reason.

“I wanted to join the guerrillas to overthrow the Chinese occupation of Tibet,” Dawa said, smiling.

A 28-year-old man at the time, Dawa firmly believed that Chinese rule could only be overthrown through armed resistance.

The first step was to convince his aging father to let him go to India.

“I told him that I wanted to go to India to study Buddhism,” Dawa said, adding that his father was a devout Buddhist and had been asking him either to get married or become a monk.

After convincing his father, Dawa traveled to Lhasa days before Losar, the Tibetan New Year, to look for someone to take him to India.

He quickly found someone who would take him, along with a dozen others, to India for 600 yuan (US$87.89) each.

Two weeks later, they left Lhasa in a van and then boarded a truck outside the city.

“The truck drove all night and dropped us off in a rural area. The driver told us we were close to the border,” Dawa said. “But in a nearby village we were told that we were still far from the border. I took out a map and found that we were actually 400km from the border.”

It was then that Dawa realized why the guide had charged so little — as the average fee for a guide usually ranges between 2,000 yuan and 3,000 yuan.

On their own and without a detailed map, they tried to find their way to India. They begged for food and slept in abandoned sheepfolds, receiving help from friendly Tibetans.

They hid from police stations and military camps, walking during the night and avoiding villages.

“Although we didn’t tell people we were going to India, to avoid trouble, most Tibetans knew and tried to help us,” he said, recalling one elderly woman who let them stay at her house and gave them 5 yuan to give to the Dalai Lama even though they told her they were pilgrims.

Other Tibetans offered food, gave directions, advised them on dangerous routes to avoid, or offered shelter.

At one point, Dawa feared for the worst after they were lost in snow-covered mountains for three or four days without food and without sight of man or beast.

“I felt I was dying, so when I was alone, because others were lagging behind, I washed my hair and my body with melted snow, and prayed for the direction to Dharamsala,” Dawa said. “In my prayer, I said: ‘If I can still do something for Tibetans, please let me live and get out of this situation; if I can’t do anything good for the Tibetan nation, please let me die here, and become someone useful for the Tibetan nation in my next life.’”

After saying the prayer, he began to feel peace, he said.

Not long after Dawa’s prayer, he and the others ran into a guide who had left the group a few days earlier, bringing back food for everyone.

Eventually, Dawa reached Nepal, and with the help of members of Tibetan communities there, he and other refugees were able to avoid Nepali police checkpoints and arrive at the exiled government’s reception center.

It was only after Dawa arrived in Dharamsala that he realized that there were no guerillas.

“At first, I thought solving the Tibetan problem through non-violent means was merely propaganda. Gradually, I realized they were serious,” he said. “Then, after studying more Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan history — since more books were available in Dharamsala — I came to understand why.”

Violence will only bring more violence, and those who use violence to achieve their objectives will only suffer from the consequences of that violence, he said.

Although Dawa was thousands of kilometers apart from his father, “I actually began to understand Father’s philosophy all of a sudden and felt closer to my father in exile.”

He said that, back home, he 苔lways thought the Buddhist philosophy his father always talked about was foolish and backward.

“When my father said I was poor to have no religion, I used to think he was poor to be such a devoted Buddhist,” he said. “But now I know he had a very sophisticated philosophical understanding.”

While it has been more than half a century since the Tibetans first went into exile, most Tibetans — including those born in exile — still believe that Tibet will be free one day.

Tashi Tsering, who runs a small business in Taipei, is a second-茆eneration Tibetan who contributes much of his energy to the Free Tibet movement.

“My parents have lived in exile in India for a long time, but they never thought about settling down in India or getting citizenship, until the last days of their lives, they still wanted to return to Tibet,” Tashi said. “I, or I should say ‘we’ second-generation Tibetans, will never forget the dreams of our parents.”

He recalled that when Tibetans in his hometown in southern India discussed marching to the Chinese embassy in New Delhi to protest and asked who would participate, his father, who was 77 at the time, raised his hand.

?he organizers told my father not to take part because he was too old, but he answered: ?? raising my hand because my son will take part.?

Tashi, who was in Nepal at the time, listened to his father and participated.

?ntil this day, whenever I take part in demonstrations, I feel that my parents ?and other Tibetans who have passed away ?are watching over us from above,?he said. ?I know that for at least 10 generations, Tibetans will not forget Tibet wherever they are.?

?ow long do you think the Chinese Communist Party regime can last??he asked.

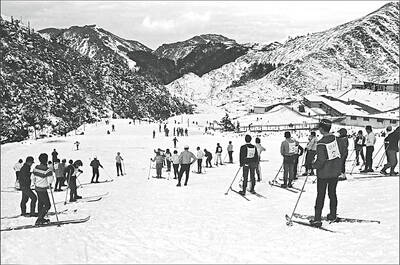

A strong continental cold air mass and abundant moisture bringing snow to mountains 3,000m and higher over the past few days are a reminder that more than 60 years ago Taiwan had an outdoor ski resort that gradually disappeared in part due to climate change. On Oct. 24, 2021, the National Development Council posted a series of photographs on Facebook recounting the days when Taiwan had a ski resort on Hehuanshan (合歡山) in Nantou County. More than 60 years ago, when developing a branch of the Central Cross-Island Highway, the government discovered that Hehuanshan, with an elevation of more than 3,100m,

Death row inmate Huang Lin-kai (黃麟凱), who was convicted for the double murder of his former girlfriend and her mother, is to be executed at the Taipei Detention Center tonight, the Ministry of Justice announced. Huang, who was a military conscript at the time, was convicted for the rape and murder of his ex-girlfriend, surnamed Wang (王), and the murder of her mother, after breaking into their home on Oct. 1, 2013. Prosecutors cited anger over the breakup and a dispute about money as the motives behind the double homicide. This is the first time that Minister of Justice Cheng Ming-chien (鄭銘謙) has

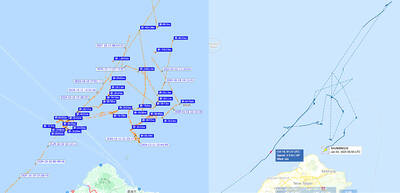

SECURITY: To protect the nation’s Internet cables, the navy should use buoys marking waters within 50m of them as a restricted zone, a former navy squadron commander said A Chinese cargo ship repeatedly intruded into Taiwan’s contiguous and sovereign waters for three months before allegedly damaging an undersea Internet cable off Kaohsiung, a Liberty Times (sister paper of the Taipei Times) investigation revealed. Using publicly available information, the Liberty Times was able to reconstruct the Shunxing-39’s movements near Taiwan since Double Ten National Day last year. Taiwanese officials did not respond to the freighter’s intrusions until Friday last week, when the ship, registered in Cameroon and Tanzania, turned off its automatic identification system shortly before damage was inflicted to a key cable linking Taiwan to the rest of

TRANSPORT CONVENIENCE: The new ticket gates would accept a variety of mobile payment methods, and buses would be installed with QR code readers for ease of use New ticketing gates for the Taipei metro system are expected to begin service in October, allowing users to swipe with cellphones and select credit cards partnered with Taipei Rapid Transit Corp (TRTC), the company said on Tuesday. TRTC said its gates in use are experiencing difficulty due to their age, as they were first installed in 2007. Maintenance is increasingly expensive and challenging as the manufacturing of components is halted or becoming harder to find, the company said. Currently, the gates only accept EasyCard, iPass and electronic icash tickets, or one-time-use tickets purchased at kiosks, the company said. Since 2023, the company said it