When Dennis Brutus heard the news, he was breaking stones on Robben Island, the notorious prison colony where Nelson Mandela, the freedom fighter and future South African president, occupied the cell next to his.

The news was that the International Olympic Committee had suspended South Africa from the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo.

That signified a victory for Brutus, who led the fight to use sports as a weapon against the racist policies of South Africa. Ultimately, South Africa was barred from almost all international athletic competitions, including the Olympics, from 1964 to 1991.

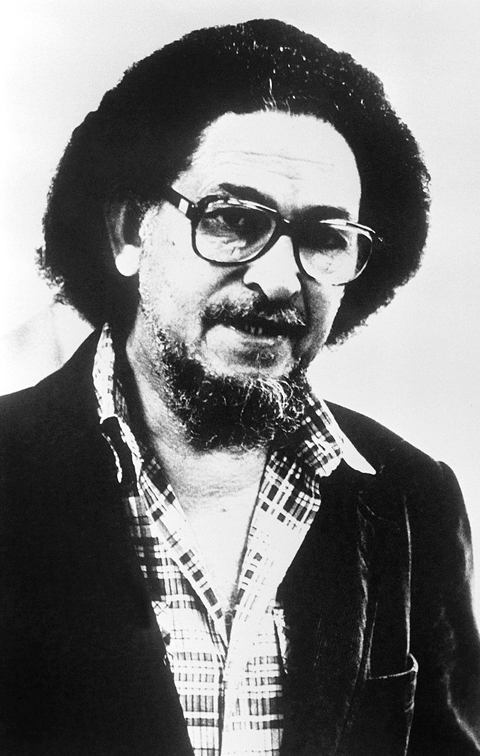

PHOTO: AFP

Brutus paid a high price for his sports activism. Besides imprisonment, he was exiled and shot in the back. A poet, teacher and journalist, he was barred from earning a living except by menial labor.

He died in Cape Town on Dec. 26 at the age of 85. His son Anthony told the South African Press Association, a news agency, that he had had prostate cancer.

There were many others from many countries who fought apartheid in sports, but Brutus helped ignite the fight, and his efforts led to big victories.

In 1995, after apartheid — the official system of racial discrimination — had crumbled, it was a sporting moment that symbolized the birth of a new democracy in South Africa. It happened during the rugby World Cup tournament, from which the country had been barred, when it was being held in Johannesburg, and Mandela, then the president, appeared at the stadium wearing the green-and-gold jersey of the country’s team, which until recently had been all white, as a symbol of national unity. (The moment is re-enacted in the film Invictus, with Morgan Freeman playing Mandela.)

‘HATED SYMBOL’

“Brutus has a distinction that makes him a hated symbol to the white rulers of South Africa, and a heroic one to the critics of their regime,” Anthony Lewis wrote in the New York Times in 1983. “He has actually succeeded in bringing about some change in one aspect of apartheid.”

Dennis Vincent Brutus was born on Nov. 28, 1924, in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), to South African parents who moved back home to Port Elizabeth when he was four. Of African, French and Italian ancestry, Brutus was classified under South Africa’s racial code as “colored.”

He graduated from the University of Fort Hare in South Africa, taught in nonwhite schools, did social work and joined the underground campaign against apartheid.

A mediocre athlete himself as a youth, Brutus turned to sports politics after seeing black athletes turned down for South Africa’s international teams in favor of inferior whites. He took up the issue not as a tactic to attack the apartheid system, he said, but because of the personal harm the policy was doing to athletes.

In 1959, Brutus helped form the South African Sports Association as founding secretary. It began by lobbying all-white sports organizations to change voluntarily, but made no progress.

In 1962, he helped form a new group to challenge South Africa’s official Olympic Committee. The organization, the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee, of which he was president, persuaded Olympic committees from other countries to vote to suspend South Africa from the 1964 and 1968 Olympics.

In 1970, the group gathered enough votes from national committees, particularly those in Africa and Asia, to expel South Africa from the Olympic movement.

For Brutus, it would be a painful road to Barcelona, where a South African team, an integrated one, returned to the Olympics in 1992.

A paper prepared by apartheid opponents for the UN in 1971 said: “Dennis Brutus, one of the most persistent campaigners against racialism in sport, became a special target of the South African regime.”

In 1960, he was barred from meeting with more than two people outside his family. When he met with a Swiss journalist and others three years later, he was sentenced to 18 months in prison.

But he jumped bail and fled to Mozambique, where the Portuguese secret police arrested him and returned him to South Africa. There, while trying to escape, he was shot in the back at point-blank range.

After only partly recovering from the wound, Brutus was sent to Robben Island, where he was imprisoned for 16 months, five in solitary confinement. On his release he was ordered not to leave his home for five years. But after a year, he made a deal to emigrate to Britain on the condition he not return to South Africa.

Four years later, Brutus moved to the US, where he taught at Northwestern University and the University of Pittsburgh. He continued to work on South African sports issues, speaking out against General Motors’ involvement in South Africa in 1970 and returning to Britain in 1971 to protest the Lawn Tennis Association’s decision to allow South African tennis players to compete at Wimbledon.

US PERSECUTION?

In a highly publicized case, US immigration authorities tried to deport Brutus in the early 1980s because he lacked proper residence documents. In an opinion article in the Times in 1982, Henry Louis Gates Jr, then a Yale literature professor, suggested that Brutus was being persecuted by the administration of then-US president Ronald Reagan for his race and leftist politics. The administration said it was simply following standing policies.

Brutus won political asylum in the US after a judge ruled he would be in danger if returned to South Africa.

Brutus is survived by his wife, the former May Jaggers; two sisters; eight children; nine grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

Taiwan kept their hopes of advancing to next year’s World Baseball Classic (WBC) alive with a 9-1 victory over South Africa in a qualifier at the Taipei Dome on Saturday, backed by solid pitching. Taiwan last night played against Nicaragua. As of press time, Nicaragua was leading 6-0. Bouncing back from Friday’s struggles on the mound, when Taiwanese pitchers surrendered 15 runs to Spain, Team Taiwan on Saturday kept the visiting team in check, allowing just one run in the bottom of the fourth inning. Starting pitcher Sha Tzu-chen struck out one and allowed no hits, except for a hit-by-pitch over

Taiwan kept its hopes of advancing to the 2026 World Baseball Classic (WBC) alive with a 9-1 victory over South Africa in a qualifier at the Taipei Dome last night, backed by solid pitching. Bouncing back from Friday’s struggles on the mound, when Taiwanese pitchers surrendered 15 runs to Spain, Team Taiwan kept the visiting team in check, allowing just one run in the bottom of the fourth inning. The win was crucial for Taiwan, as a loss would have eliminated the team from contention for the next WBC. Starting pitcher Sha Tzu-chen (沙子宸) struck out one and allowed no hits, except for

Team Taiwan are set to face Spain in a win-or-go-home match tonight for the final berth at the 2026 World Baseball Classic (WBC), despite losing to Nicaragua 6-0 in the WBC qualifier at the Taipei Dome on Sunday. The home team’s loss on Sunday means Nicaragua finish first in the qualifier round in Taipei with a perfect 3-0 record and advances to next year’s finals. After crushing South Africa 9-1 earlier on Sunday, Spain took second place in the four-team qualifier with a 2-1 record. With a 1-2 record, Taiwan finished third while South Africa placed at the bottom with

Team Taiwan avoided missing the World Baseball Classic (WBC) for the first time by defeating Spain 6-3 in a do-or-die game in Taipei last night. After narrowly escaping a mercy-rule loss to Spain in the WBC Qualifiers opener on Friday last week, the home team — winner of last year's WBSC Premier12 title three months ago — got their revenge against the 2023 European champions at Taipei Dome. "It felt quite different from when we won the Premier12," Taiwan captain Chen Chieh-hsien (陳傑憲) said after the game, recalling the ups and downs the team has experienced over the past few days. Unlike in