Chinese practice

緣木求魚

(yuan2 mu4 qiu2 yu2)

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

climb a tree to catch a fish

我朋友不是傻瓜,但他剛開始做他第一份工作時,老闆就派他去做一連串「傻瓜的差事」(fool’s errands)。老闆叫他去五金行買一個沒有水平儀的氣泡,店員道歉說,他們只賣一整組的,沒辦法分開來賣。幾天後,老闆叫他去買一些蘇格蘭格子紋油漆。後來,老闆又叫他去買一把左手用的槌子。

「fool’s errands」是沒有指望會成功的任務或行動,常被當做一種菜鳥訓練儀式或惡作劇,通常是團隊中有經驗的前輩叫新人去做,就像我朋友和他那愛開玩笑的老闆一樣。

此語之歷史並不特別久遠,最早的出處之一,是一七○五年的書《Priest-craft: Its Character and Consequences》(教士的權術:其性質與後果),作者為埃德蒙‧希克里格,書中有這句:「Did not the Pope send all the Princes in Christendom upon a Fools Errand, to gain the Holy Land, that he might (as he did in their absense) rob them of their territories.」(教皇難道不是差派所有基督教世界的王子們去做那傻瓜的差事、取得聖地,好讓教皇(趁王子們不在時)奪取他們的領地嗎?)

「fool’s errand」一語的歷史雖不長,但它背後的概念,在之前數世紀便以「sleeveless errand」(無袖的差事)這不同的形式出現,例如威廉‧莎士比亞一六○二年的悲劇《特洛伊羅斯與克瑞西達》(又譯「特洛埃圍城記」)中即有此語。在約一七○○年之前,形容詞「sleeveless」顯然是用來表示「徒勞」或「用處不大」,雖然我們並不知道為何「sleeveless」或其同義詞「without sleeve」會有這種含義。當「sleeveless」不再有「徒勞」之意後,句中的「sleeveless」就被現今意義的「fool」一字所取代(「fool」字現今的意義已跟過去不同,現指無知、缺乏判斷力或不謹慎的人),變成「fool’s errand」。

在中文裡,成語「緣木求魚」──字面意思是「爬到樹上去捕魚」──是用來指一種不智的、無意義或註定要失敗的行動。此語出自儒家經典《孟子》。孟子向齊宣王講述國家富強之道,孟子認為,要達到這目標,唯一的方法是行仁政──要先把自己的家打理好、為建立繁榮的國家確實奠定基礎,然後人們才會想要為他效勞,人才才會湧入該國。然而,齊宣王所做的並不是這些事。孟子對齊宣王說:「欲闢土地,朝秦楚,蒞中國而撫四夷也。以若所為求若所欲,猶緣木而求魚也」(您是想要擴張國土,使秦、楚這些大國都來朝貢您,自己君臨中國,安撫四方落後的民族。不過,要實現這願望,您現在的做法就好像是爬到樹上去捉魚一樣)。

成語「緣木求魚」也出現在幾部中國文學作品中,例如蒲松齡的《聊齋誌異》(作於十七世紀末十八世紀初):「緣木求魚,狼則罹之,亦可笑已」(就像爬上樹去捉魚一樣,狼本來想吃肉,結果卻遭遇了禍患,真是可笑啊!)。此語亦見於李汝珍一八二七年的奇幻小說《鏡花緣》:「今處士既未立功,又未立言,而又無善可立;一無根基,忽要求仙,豈非「緣木求魚」,枉自費力麼?」(你既沒有立下功績,也沒有發表重要的言論,且又沒有做善事;你完全沒有根基,卻忽然要求神仙之道,這難道不是「緣木求魚」、白費自己的力氣嗎?)

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

(You haven’t worked hard at all; all you’ve done is ask lots of fortune tellers for readings. You have absolutely no chance of doing well.)

(He’s too selfish, asking him for his help is pointless, you’ll just be wasting your breath.)

英文練習

fool’s errand

My friend is no fool, but when he started his first job, his boss sent him on a series of fool’s errands. He asked him to go to the hardware store and buy a bubble without the spirit level: the sales assistant apologized and said they only sold them as a set. A few days later, the boss sent him off to buy some tartan paint. After that, he asked for a left-handed hammer.

A fool’s errand is a task or activity with no hope of success. It is often used as a kind of rite of initiation or practical joke, usually by a senior, experienced member of a team against a newcomer, as with my friend and his playful boss.

The term itself is not particularly old: one of the first references is from the 1705 book Priest-craft: Its Character and Consequences by Edmund Hickeringill, in which we find the sentence “Did not the Pope send all the Princes in Christendom upon a Fools Errand, to gain the Holy Land, that he might (as he did in their absense) rob them of their territories.”

The concept behind “fool’s errand,” however, predates the phrase by several centuries, in a different form: a “sleeveless errand.” We see this phrase, for example, in William Shakespeare’s 1602 tragedy Troilus and Cressida. The adjective “sleeveless” apparently used to mean “futile” or “of little practical use” until around the 1700s, although it is unclear exactly why the word “sleeveless” — with its alternative meaning of “without sleeves” — should carry that meaning. When the word “sleeveless,” in the sense of “in vain,” fell into disuse, it was substituted in the phrase by the word “fool,” in its modern sense (for it has changed) of an ignorant person, or one lacking in judgment or prudence.

In Chinese, the idiom 緣木求魚 — literally “to climb a tree to catch a fish” — is used to refer to an activity that is ill-conceived, pointless or otherwise doomed to failure. It comes from a passage in the Confucian classic the mengzi, in which Mencius is advising King Xuan of the state of Qi how to make his state strong. Mencius insists that the only way to do so would be to follow the principles of benevolent government, by first setting one’s own house in order and laying the proper foundations for a prosperous state, after which people will want to serve him, and the talented will flock to his lands, but that this is not what the king is doing. Mencius says to the king 欲辟土地,朝秦楚,莅中國而撫四夷也。以若所為求若所欲,猶緣木而求魚也: “You wish to enlarge your territories, to have Qin and Chu wait at your court, to rule the Middle Kingdom, and to attract to you the barbarous tribes that surround it. But doing what you do to seek for what you desire is like climbing a tree to seek for fish.”

The idiom appears in several works of Chinese literature. In Pu Songling’s liaozhai zhiyi (Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio), written in the late 17th and early 18th century, appears the line 緣木求魚,狼則罹之,亦可笑已 (Just like climbing a tree to catch a fish, the wolf, hoping to dine on meat, got itself in real trouble. How ridiculous!), and in Li Ruzhen’s 1827 fantasy novel jinghua yuan (The Marriage of Flowers in the Mirror), we find the sentence 今處士既未立功,又未立言,而又無善可立;一無根基,忽要求仙,豈非『緣木求魚』,枉自費力麼? (You have neither achieved anything nor said anything of note, nor have you performed any good deeds; you have absolutely no basis on which to seek the Way of the Immortals. Surely, you are wasting your time, running this fool’s errand).

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

(我很樂意把你的歉意轉告給你媽,但我不覺得她會接受。這恐怕是緣木求魚。)

(派新人去做一些「緣木求魚」的傻事並非出於惡意,而只是一種破冰的方式。)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

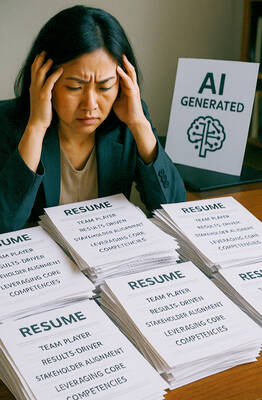

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight