Chinese Practice

及時行樂

(ji2 shi2 xing2 le4)

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

enjoy the present

許多人第一次聽到拉丁格言「carpe diem」──英文為「seize (pluck) the day」(把握今朝)──很可能是在一九八九年的電影「春風化雨」(Dead Poets Society),這部片的故事是美國一所預科名校學生的教育。這些學生所研讀的已作古的詩人,一定也包括英國浪漫主義詩人拜倫(西元一七八八~一八二四年)。拜倫在一八一七年寄自威尼斯的信中,提到一段萌芽中的愛情,拜倫寫道:「到目前為止,我們的進展非常順利;至於未來,我不去預測──『carpe diem』──過去已成無法改變的既定事實,這也是我們為什麼要把握當下。」拜倫的意思是說,他願意讓事情自然發展,並在機會來臨時抓住它,去「make sure of the present」(把握當下)。一般認為這是「carpe diem」這拉丁片語第一次在英文出版品中出現。

拜倫精通拉丁文,以及羅馬詩人賀拉斯(西元前六五~前八年)的作品。拜倫在一八一一年寫了《Hints from Horace》(賀拉斯的啟示),這是他對賀拉斯的《Ars Poetica》(詩藝)的詮釋。想必他可由賀拉斯的《Odes Book I》(詩集第一卷)──也就是「carpe diem」的出處,得知此語:

「Dum loquimur, fugerit invida aetas: carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero」(我們說話的當下,善妒的時間正在流逝:把握今朝,別相信未來)。

賀拉斯的意思是說,時間過得很快,我們在世上的時間很短暫:我們沒有時間坐在這裡說話,我們應該做對現在最好的事,毫不拖延,而不是假設未來還會有機會,甚至根本就不會有未來。

這個片語可以單獨使用,以拉丁文「carpe diem」或英文「seize the day」(把握今朝)的形式,或者是用原始片語的擴充翻譯:「Seize the day, put very little trust in tomorrow.」(把握今朝,別太相信明天)。

和「carpe diem」意思相近的中文,是成語「及時行樂」,意思是「享受現在」,或「快樂地生活,不去考慮未來」,可見諸《大宋宣和遺事》和明代汪廷訥的《種玉記》。

《大宋宣和遺事》的作者不詳,但這部作品被認為是中國文學四大經典小說之一的《水滸傳》的前身(作者推為施耐庵,生卒年約為西元一二九六~一三七二年),其中有許多民間故事,後來也收錄在《水滸傳》中。《大宋宣和遺事》分為四個部分;其中〈亨集〉一部,有這麼一句:「人生如白駒過隙,倘否及時行樂,則老大徒傷悲也」(生命就像一隻白色小馬跑過岩石間的裂隙,如果你不抓住現在,以後老了就會後悔)。在《種玉記》第二十八齣中,則有:「我和你正好向花前月底,及時行樂,相賞依違」(你和我,發現我們置身於花叢中,在月光下。我們應該把握此刻,享受親密關係)。

在這兩個例子中,成語「及時行樂」和英文中「carpe diem」的用法大致相同,都是用來表示抓住時機──現在可以做的事,不要拖到未來。

前面引文的開頭部分是另一個成語「白駒過隙」──雖然本週介紹的成語意為把握今天、事不宜遲,但此處我們要有些反諷地說,成語「白駒過隙」,將留待下週的「活用成語」單元來介紹。

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

人生苦短,應及時行樂,愛也要及時說出口,才不會有遺憾──這就是我的人生哲學。

(Life is brutish and short, so make the best of things when you can. If you love someone, you should tell them, otherwise you will regret it. That is my philosophy of life.)

英文練習

carpe diem; seize the day

For many, the first time they’d ever heard the Latin phrase carpe diem — “seize (pluck) the day” — may well have been in the 1989 movie Dead Poets Society about the education of the students of an elite US prep school. One of the dead poets the boys would have studied could well have been the British Romantic poet Lord Byron (1788-1824). In an 1817 letter written from Venice and referring to a potential love affair, Byron wrote “So far we have gone on very well; as to the future, I never anticipate — carpe diem — the past at least is one’s own, which is one reason for making sure of the present.” He was saying that he was willing to see how the situation unfolded, and to seize the opportunity as it transpired, to “make sure of the present.” This is thought to be the first time this Latin phrase was published as part of an English text.

Byron knew Latin well, and was well-versed in the work of the Roman poet Horace (65BC –8BC). In 1811, Bryon wrote Hints from Horace, his version of Horace’s own Ars Poetica (The Art of Poetry). He would have known carpe diem from the original source of the phrase — Horace’s Odes Book I — where we find:

“Dum loquimur, fugerit invida aetas: carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero” (while we’re talking, envious time is fleeing: pluck the day, put no trust in the future).

Horace’s message here was, time is passing quickly, and our time on the Earth is short: we have no time to sit here talking, and we should do what is best for now with no further delay, and not assume that there will be another opportunity in the future, nor indeed any future at all.

The phrase can be used on its own, in its Latin (carpe diem) or English (seize the day) format, or as the extended translation of the original phrase: “Seize the day, put very little trust in tomorrow.”

A good Chinese alternative to carpe diem is the idiom 及時行樂, meaning “to enjoy the present,” or “to live happily, with no thought for the future.” Two notable references in Chinese literature are to be found in dasong xuanhe yishi (Old Incidents in the Xuanhe period of the Great Song Dynasty) and in a Ming Dynasty book, zhongyu ji by Wang Tingna.

It is unknown who wrote Old Incidents, but the work is considered a precursor to the Water Margin, one of the four great classical novels of Chinese literature, attributed to Shi Naian (ca. 1296–1372), and contains many of the folk stories which would later be included in it. Old Incidents was divided into four sections; in one of these sections, the hengji, is the line 人生如白駒過隙,倘不及時行樂,則老大徒傷悲也 (Life is like a white colt flitting past a fissure in the rock; if you do not seize the present, you will regret it in old age). In Chapter 28 of the zhongyu ji, we read 我和你正好向花前月底,及時行樂,相賞依違 (You and I, we find ourselves among the flowers, with the moon shining upon us. We should make use of this moment, and enjoy each others’ company).

In both cases, the authors are using 及時行樂 in much the same way we might use carpe diem in English, to seize the moment and not put off for the future what can be done in the present.

Embedded in the former quote is another idiom, 白駒過隙. Using Idioms will look at this next week, ironically putting off for the future what could conceivably be done today.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

If we’re going to do it, we should do it now. There is no time like the present: carpe diem.

(如果你要做這件事的話,現在就做。要把握當下,沒有比現在更好的時機了。)

Skating is a popular recreational and competitive activity that involves sliding over surfaces using specially designed footwear. Its origins date back over 1,000 years to Northern Europe, where people first strapped animal bones to their feet to move across frozen lakes and rivers. In the 17th century, the Dutch transformed skating into a leisure activity. They also replaced bone blades with metal, leading to the creation of modern ice skates. Today, ice skating is enjoyed as a global sport and an exciting pastime by people of all ages. Figure skating is one of the best-known and most graceful forms of skating.

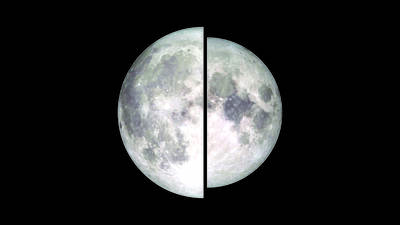

Have you ever gazed at the night sky and felt as though the Moon loomed larger than usual? Your eyes were not deceiving you. The Moon’s apparent size can __1__ subtly depending on where it is in its orbit. On certain occasions, it reaches its fullest phase while at its closest point to Earth. When these two events __2__, scientists and the public refer to the spectacle as a “supermoon.” The Moon does not orbit our planet in a perfect circle. Instead, it travels along a more oval-shaped __3__, completing one full orbit every 27 days. Consequently, there are times when

A: South Korea’s Golden Disc Awards ceremony is taking place at the Taipei Dome on Saturday. Eighteen acts are taking to the stage, including Blackpink’s Jennie. B: The hottest boy group CORTIS is also performing. I can’t wait to see James, the Taiwanese member of the band, perform. A: Who else are playing at the K-pop show? B: This year’s lineup is stacked, including: Allday Project, ARrC, Ateez, Boynextdoor, Close Your Eyes, Enhypen, IVE, Izna, KiiiKiii, Le Sserafim, Monsta X, NCT Wish, Stray Kids, TWS, Zerobaseone and Zozazz. A: SKZ, Enhypen and Ateez dominated Billboard’s 2025 Year-End World

A: Aside from K-pop, what were the English chart-toppers? B: Billboard’s top three singles for 2025 were “Die with a Smile” by Lady Gaga/Bruno Mars, “Luther” by Kendrick Lamar/SZA and “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” by Shaboozey. Plus, pop diva Mariah Carey’s 1994 megahit “All I Want for Christmas Is You” won its 20th and 21st weeks at No. 1, becoming the longest-running No. 1 song in history, A: How about in Taiwan? The news says nine of the 10 most-streamed songs on Spotify Taiwan were Korean. B: Yup, and the top three were: “Winter Ahead” by BTS’ V and Park