Chinese practice

打草驚蛇

beat the grass to scare the snakes

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

(da2 cao3 jing1 she2)

「pocke」這個字源自中古英語「poket」,意為小型的「poke」(袋子)(以「et」或「ette」結尾是表示它是某物的迷你版,例如「cigarette」(香煙)是小的雪茄(cigar)的意思)。在中世紀時,「poke」指的是可以用來裝小型家畜家禽(例如小豬)到市場上去賣的袋子,短語「pig in a poke」即源於此——在許多歐洲語言中都有類似的說法。但「pig in a poke」也暗含一種警告:如果你打算在市場裡買一隻小豬,一定要先往袋子裡檢查一下。因為在十六世紀的歐洲有個常見的騙術,就是把小豬換成一隻貓來矇混。小豬會長成大豬,經濟上會變得很有價值,而貓除了幫農場抓老鼠很有用外,沒有什麼其他的價值。

買家應該要小心:貨物售出,概不退換,買家當提防。因此,若無良賣家要確保他們的欺騙伎倆在交易完成前不露餡,他們就該如同這俗語所說的,不要「let the cat out of the bag」(讓貓從袋子裡出來)。

這句話其實就是一種警告——在對某些人隱藏某些事情是有用處時,不要讓他們知道那些機密訊息;一切終會真相大白,但保守秘密對目前來說至關重要。

英格蘭作家約翰‧海伍德(約西元一四九七~約一五八○年)在他的《Proverbes and Epigrammes》(諺語和箴言)中,便寫下一句箴言,包含了此片語,提醒人買貨之前須小心提防:

「I will neuer bye the pyg in the poke: [我絕不會買用袋子包起來的小豬]

Thers many a foule pyg in a feyre cloke. 」[掩蓋的表面下多是骯髒的豬]

《三十六計》中的第十三計是「打草驚蛇」(關於《三十六計》的介紹,請見五月十四日「活用成語」單元),「打草驚蛇」字面意義為擊打草來嚇唬蛇,其衍伸意義為,不小心讓敵人警覺到我們的存在或計謀。「打草驚蛇」這個說法很有畫面,其意義的確也不言自明。成語「打草驚蛇」出自宋代學者鄭文寶的《南唐近事》,現在多用於否定句中,例如「不要打草驚蛇」(不要擊打草,讓蛇有所警覺),意思是不要讓別人知道你正在做的事。

鄭文寶此書中有個故事,描述南唐時期,一個名叫王魯的貪腐縣令收到一份投訴,說他有個下屬收受賄賂,卻也讓王魯意識到他自己同樣也犯了這收賄的罪。他在這投訴書上批示道:「汝雖打草,吾已?驚」——你們雖然只是用棍子打草叢,但我就像藏身在草叢裡的蛇,已經有所警惕。即使這件投訴不是針對王魯,卻已讓他警覺到被抓的危險。

「打草驚蛇」也出現在中國文學其他作品,包括明代小說《西遊記》。在第六十七章有這樣一句:「行者見了笑道:『妖怪走了,你還撲甚的了?』八戒道:『老豬在此打草驚蛇哩!』」(僧人看了,便笑著說:「妖怪已經消失了,你還在打什麼?」豬八戒說,「我正在打草驚蛇哩!」)

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

警方怕打草驚蛇,導致嫌犯逃逸,因此先在附近部署攻堅警力,再一步一步逼近。

(The police, not wanting to alert the suspect and risk them escaping, first deployed a strong police presence in the area and then closed in.)

園丁在清除雜草前不小心打草驚蛇,草叢中突然竄出一隻青竹絲,狠狠咬了他一口。

(The gardener inadvertently disturbed a snake as he was clearing away the weeds, and a viper sprang out of the underbrush and gave him a nasty bite.)

英文練習

let the cat out of the bag

The word “pocket” derives from the Middle English poket, a diminutive — ending in “et” or “ette,” as in a “cigarette” being a “small cigar” — version of poke. In the Middle Ages, a poke would have been a bag suitable for taking small livestock, such as a piglet, for sale at market. The phrase “pig in a poke” — which appears in many European languages in one form or the other — is a direct reference to this, but also alludes to a caution: If you are going to buy a piglet at market, make sure you look inside the bag first. A common trick at the time, in 16th century Europe, was to substitute a piglet — which would grow into an economically valuable pig — for a cat, which might be good for killing rats on the farm, and little else.

The buyer should be careful: caveat emptor, buyer beware. So, indeed, should the unscrupulous seller, who needs to make sure their deceit is sufficiently concealed until the deal is complete and the buyer has gone home. They should not, as the saying goes, “let the cat out of the bag.”

This phrase has come down to us as a warning not to let certain confidential information be known while it is useful to keep it concealed from certain other people; all will be revealed eventually, but for the time being it is important to keep the secret to ourselves.

The English writer John Heywood (c. 1497 – c. 1580), in his Proverbes and Epigrammes, wrote an epigram including the phrase, speaking of the need to be aware of what you are buying before you commit:

“I will neuer bye the pyg in the poke: [I will never buy the pig in the poke]

Thers many a foule pyg in a feyre cloke.” [So often you find a foul pig in a fair cloak]

The 13th strategy in the sanshiliu ji (Thirty-six Strategems, see Using Idioms on May 14) is 打草驚蛇, literally to beat the grass to scare the snakes or, by extension, to inadvertently alert an enemy to one’s presence or one’s plans. The imagery is quite self-explanatory, of course. The idiom, thought to derive from a reference in the nantang jinshi (A Modern History of the Southern Tang Dynasty) written by Song Dynasty scholar Zheng Wenbao, is now generally used in a negative sentence, that is, “don’t beat the grass and alert the snake,” to mean to avoid any action that will alert others to what you are doing.

A story in Zheng’s book tells of how a corrupt county magistrate of the Southern Tang named Wang Lu received a complaint about how one of his subordinates had been taking bribes, and he realized that he was also guilty of the crimes being brought before him. He wrote a commentary on the document, 汝雖打草,吾已?驚: “you have beaten the grass, and now I, like a snake concealed within, have been startled.” Wang had been alerted to the danger of being caught, even though the complaint was not directed at him.

It has appeared in other works of Chinese literature, too, including the Ming Dynasty novel the xiyou ji (Journey to the West). In chapter 67 there is the line 行者見了笑道:『妖怪走了,你還撲甚的了?』八戒道:『老豬在此打草驚蛇哩!』: “Seeing this, the monk said, laughing, ‘the monsters have gone, so why are you still thrashing around?’ Zhu Bajie said, ‘I’m just trying to scare off the snakes.’”(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

Remove your shoes; walk softly. We don’t want to let the cat out of the bag and wake them.

(把你鞋子脫掉,走路小聲點,我們不要打草驚蛇,把他們吵醒。)

The police have got involved and are investigating our past shady deals. Now the cat’s really out of the bag.

(警察已經介入調查我們以前的可疑交易,現在東窗事發了。)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

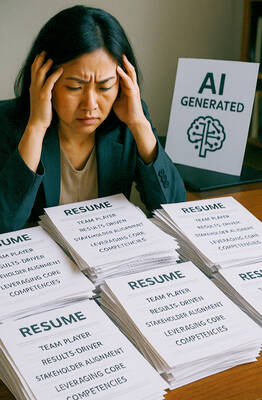

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight