Globalization is under strain as never before. Every-where its stresses rumble. Most of sub-Saharan Africa, South America, the Middle East and Central Asia are mired in stagnation or economic decline. North America, Western Europe and Japan are bogged down in slow growth and risk renewed recession. War now beckons in Iraq.

For advocates of open markets and free trade this experience poses major challenges. Why is globalization so at risk? Why are its benefits seemingly concentrated in a few locations? Can a more balanced globalization be achieved?

No easy answers to these questions exist. Open markets are necessary for economic growth, but they are hardly sufficient. Some regions of the world have done extremely well from globalization -- notably East Asia and China in recent years. Yet some regions have done miserably, especially sub-Saharan Africa.

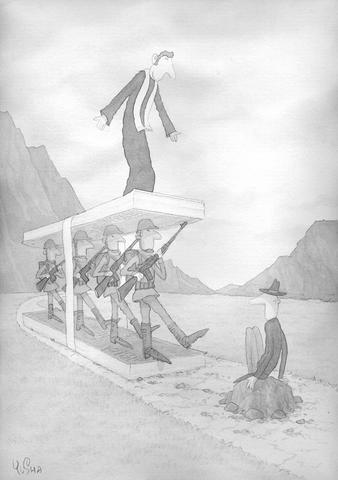

ILLUSTATION: MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

The US government pretends that most problems in poor countries are of their own making. Africa's slow growth, say American leaders, is caused by Africa's poor governance. Life, however, is more complicated than the Bush administration believes. Consider Africa's best governed countries -- Ghana, Tanzania, Malawi, Gambia. Each experienced falling living standards over the past two decades while many countries in Asia that rank lower on international comparisons of governance -- Pakistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar and Sri Lanka -- experienced better economic growth.

Rapid growth

The truth is that economic performance is determined not only by governance standards, but by geopolitics, geography, and economic structure. Countries with large populations, and hence large internal markets, tend to grow more rapidly than countries with small populations. (Like all such economic tendencies, there are counterexamples).

Coastal countries tend to outperform landlocked countries. Countries with high levels of malaria tend to endure slower growth than countries with lower levels of malaria. Developing countries that neighbor rich markets, such as Mexico, tend to outperform countries far away from major markets.

These differences matter. If rich countries don't pay heed to such structural issues, we will find that the gaps between the world's winners and losers will continue to widen. If rich countries blame unlucky countries -- claiming that they are somehow culturally or politically unfit to benefit from globalization -- we will create not only deeper pockets of poverty but also deepening unrest. This, in turn, will result in increasing levels of violence, backlash and yes, terrorism.

So it's time for a more serious approach to globalization than rich countries, especially America, offer. It should begin with the most urgent task -- meeting the basic needs of the world's poorest peoples. In some cases their suffering can be alleviated mainly through better governance within their countries. But in others, an honest look at the evidence will reveal that the basic causes are disease, climatic instability, poor soils, distances from markets and so forth.

An honest appraisal would further show that the poorest countries are unable to raise sufficient funds to solve such problems on their own. Rather than rich countries giving more lectures about poor governance, real solutions will require that rich countries give sufficient financial assistance to overcome the deeper barriers.

One illustration makes the case vividly. Controlling disease requires a health system that can deliver life-saving medications and basic preventive services such as bed-nets to fight malaria and vitamins to fight nutritional deficiencies. Such a system costs, at the least, around US$40 per person per year.

That's a tiny amount of money for rich countries, which routinely spend over US$2000 per person per year for health, but it is a sum out of reach for poor countries like Malawi, with annual incomes of US$200 per person. A functioning health system would cost more than its entire government revenue! Even if Malawi is well governed, its people will die of disease in large numbers unless Malawi receives adequate assistance.

Good doctors

Successful globalization requires that we think more like doctors and less like preachers. Rather than castigating the poor for their "sins," we should make careful diagnoses, as a good doctor would, for each country and region -- to understand the fundamental factors that retard economic growth and development.

In some regions, such as the Andes and Central Asia, the problem is primarily geographical isolation. Here the task is to build roads, air links and internet connectivity to help these distant regions create productive ties with the world. Rich countries must help finance these projects.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the basic challenges are disease control, soil fertility, and expanded educational opportunities.

Once again, greater foreign assistance will be needed. In still other regions, the main problems may be water scarcity, discrimination against women or other groups, or one of a variety of specific problems.

It is past time to take globaliza-tion's complexities seriously. The one-size-fits-all ideology of the Washington Consensus is finished. As we stand at the brink of war, it is urgent that the hard job of making globalization work for all gets started.

This can be done, if we remove the ideological blinkers of the rich and mobilize a partnership between rich and poor. Our common future depends on it.

Jeffrey D. Sachs is professor of economics and director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its