When Chris Berry first started watching Hoklo- (also known as Taiwanese) language films in the late 1990s, his Taiwanese friends and colleagues dismissed them as garbage.

“Taiwan’s film world was very much in an art film mindset,” Berry says, referring to the period where New Wave pioneers such as Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝賢) and Edward Yang (楊德昌) earned the nation an international arthouse following.

By then, the more than 1,000 crudely-produced and often tawdry Hoklo movies that were pumped out between 1956 and 1981 had largely been forgotten, and it didn’t help that the government strongly supported Mandarin movies and painted Taiwanese culture as vulgar. Only about 200 titles remain today, and the Taiwan Film Institute (國家電影中心, TFI) has been slowly restoring and subtitling them since 2013.

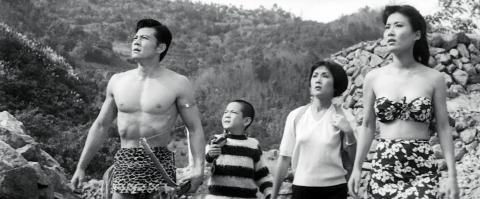

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film Institute

That year was when Ming-yeh Rawnsley (蔡明燁), a professor at the University of London’s Center of Taiwan Studies, first delved into Hoklo cinema through her research.

“It was very shocking to me, because Hoklo-language films were still around when I was young, but I don’t have any recollection of them. It wasn’t even that long ago,” she says.

Last month, Berry, a film professor at King’s College London and Rawnsley launched the second edition of Taiwan’s Lost Commercial Cinema: Restored and Recovered tour through Europe, which will cover 21 cities by December. Selections include the latest titles restored by the TFI as well as four shorts by modern auteurs that make use of footage from the old films. Their first effort, which began in 2017, was academically-focused, but having established a reputation they are branching out to arthouse theaters and film festivals as well.

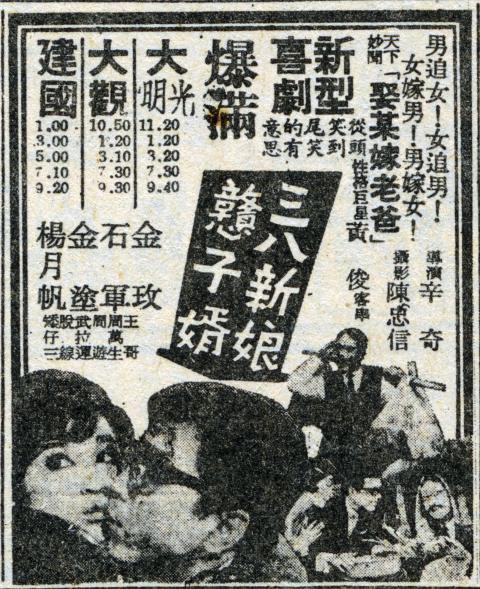

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film Institute

The tour won’t be coming to Taiwan as it is aimed to promote the nation’s culture overseas — but the films are available for viewing at the TFI.

MORE THAN NOSTALGIA

With the bulk of Hoklo cinema’s corpus unavailable when she began her research, Rawnsley says it was like “studying film history without films.” The titles Berry initially found didn’t even have Chinese subtitles, making the task even more difficult.

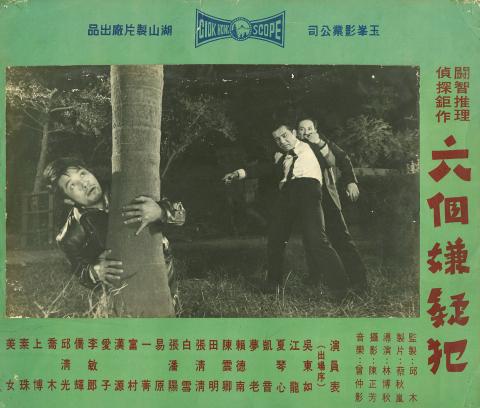

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film Institute

Unlike other locales such as the US and Hong Kong where their classic cinema has remained popular and readily available, Taiwan’s old movies are hard to find.

“The interest is more than nostalgia for Taiwanese,” Rawnsley says. “‘It’s rediscovering our past and reconfirming our current identity. It’s very important for cultural preservation to restore these films, but it’s a shame that Taiwanese still don’t have many opportunities to watch them.”

Most of these films were shot on location instead of the studio, and produced outside of the tightly-controlled government system. Although they were also subject to censorship, they provide glimpses into Taiwan’s past that may not be found elsewhere.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Film Institute

“Almost everything we see now from that era is from the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) point of view,” Berry says. “So by intention or by accident, we … get the perspectives on social changes and developments from ordinary people, and … we get to see what ordinary Taiwan looked like then.”

Outside of Taiwan, it was hard to promote these films at first because they are hard to define: “They’re not arthouse films, they’re not like today’s commercial productions, and their ideology is very mainstream — it’s not resistance cinema. It doesn’t really fit what most theaters and film festivals are used to,” Rawnsley says.

But Berry says that changing preferences have contributed to their success.

“It helps that the days when cinephiles were exclusively interested in high art cinema are over,” he says.

LIMITED RESOURCES

Berry proposes Hoklo cinema as an “alternative cinema of poverty,” in the sense that facing budget constraints, the filmmakers engaged in “an exuberant process of borrowing, bricolage and improvisation that drew from other cinemas around the world to produce a distinctly Taiwanese cinematic form.”

Berry adds that the term “poverty” isn’t meant as an insult, but a compliment to Hoklo cinema’s “can-do spirit of improvisation.”

The two Japanese-trained filmmakers featured in this tour, Hsin Chi (辛奇) and Lin Tuan-chiu (林摶秋) both had to make the best of their circumstances, which also included government censorship and pressure from the film companies to succeed in a tight market.

“Their work reflects how filmmakers who lived through the transition from Japanese to KMT rule tried to make a living and pursue their artistic ideals — while maintaining certain control over what they wanted to portray,” Rawnsley says.

Lin, who faced less economic pressure, hoped to improve the production quality of Hoklo cinema while highlighting the struggles of women in a patriarchal society; Hsin was more concerned about quantity but also sought to explore various social issues.

“By focusing on these two fillmakers, TFI is challenging the idea that Taiwanese-language cinema is only a genre cinema, and making us think about its auteur dimensions,” Berry says.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

Since the films don’t fit a definite genre, it’s crucial to present their cultural context through post-screening discussions. Rawnsley and Berry put on over 20 screenings at 10 locations during their first tour, but continued to show the films across Europe on demand until taking a break last May.

Rawnsely was surprised at the richness of the themes that emerged — from the Taiwanese interpretation of gothic horror in Bride in Hell (地獄新娘) to whether the KMT showed any of these films abroad as Cold War propaganda.

Since some of them did fit the Cold War ideology, the fact that the government ignored them led to more discussion on Martial Law-era politics and how it affected the nation’s cultural development.

Rawnsley also noticed that people from different backgrounds interpreted the same events differently — after screening The Fantasy of the Deer Warrior (梅花鹿大俠), a Japanese man saw the wolf scheming to eat the animals as Japan’s historic relationship with Taiwan and China; she saw it as the Chinese Communist Party threatening Taiwan, while a young Taiwanese student said that it was the KMT oppressing Taiwanese.

One genre that global audiences can easily relate to is the melodrama of development, Berry says, referring to the storylines that focus on the risk and rewards of moving from the countryside to the city such as Last Train Out of Kaohsiung (高雄發的尾班車). The pessimism of these plots provides a contrast to the better-known “healthy realism” (健康寫實) productions that the KMT favored as internal propaganda for economic development and social order.

And sometimes, it just took common political circumstances for the audience to connect to the films. Berry noticed the audience growing larger over three screenings in Lithuania, where they “understood the situation of Taiwan almost instinctively.”

“The idea of being a small country with a big brother neighbor that it is not too comfortable with, and also an internally mixed population with different languages, some of whom connect more to that neighbor — the Lithuanians did not need us to explain much about that,” he says.

For more information, visit the project’s Web site: www.taiyupian.uk. TFI’s Web site is: www.tfi.org.tw.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she