Feb. 10 to Feb. 16

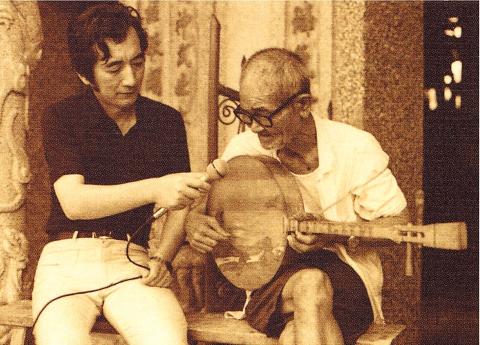

Chen Ta (陳達) was a destitute old man living alone in a shack when Hsu Chang-hui (許常惠) “discovered” him in July 1967. When the illiterate 62-year-old picked up the yueqin (月琴), or moon lute, and started to play, Hsu knew immediately that he was hearing something extraordinary.

When he returned to Taipei, Hsu couldn’t wait to play a recording that he had made of Chen to his fellow researcher, Shih Wei-liang (史惟亮).

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Music Institute

“It’s like finally finding the precious treasure that we’ve been searching for for so many years!” Shih exclaimed.

This was the high point of the duo’s Taiwan folk music collection initiative, which involved over 20 field researchers and yielded over 2,000 recordings in under two years. They found Chen on the final trip, where Hsu led a team down the west coast while Shih took on the east. They reconvened in Taipei to share their findings, which covered nine indigenous peoples as well as the Hakka and Hoklo people.

Hsu’s journal during the trip reflects their motives, lamenting that people who knew Taiwanese folk songs saw them as vulgar and were reluctant to sing them, and the few “connoisseurs” who enjoyed traditional Chinese music saw these rural tunes as uncultured.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Music Institute

“Nowadays, people are enthralled with Western-style music without even understanding it,” he writes.

OUR OWN MUSIC

Growing up in rural Changhua in the 1930s, Hsu was constantly exposed to Taiwanese folk music. But he didn’t start using these and other Chinese elements in his work until he studied in Paris, referring to them as his “musical mother tongue.”

Shih, on the other hand, did not grow up in Taiwan. Born in northeastern China, he joined the underground resistance against the Japanese as a teenager and didn’t start learning music until 1947, when he enrolled in Beijing University and studied composition under famed Taiwanese musician Chiang Wen-ye (江文也). Shih moved Taiwan in 1949 and to Europe afterward, where he too realized the importance of using traditional music in modern compositions.

Both cited Hungarian composer Bela Bartok, who collected folk music and incorporated it into his work, as a major inspiration. They sought to emulate Bartok’s balancing of tradition and modernity.

Shih writes that Bartok “was neither a narrow-minded nationalist, nor an absurd globalist.”

Hsu writes in Draft of Taiwan Music History (台灣音樂史初稿) that the 1960s was a time where the influx of Western culture had superseded traditional art forms.

“Once a new trend starts, the old things are immediately abandoned,” he writes.

In 1962, Shih published an op-ed, “Do we need our own music?”, in the United Daily News. Hsu responded to Shih in a letter to the editor: “We do need our own music.”

“We look down on our own music, we look down on our feelings and even deny our feelings,” he writes. “Vienna conquered the whole world [musically] but never lost its soul. Not only have we not made any gains musically, we are walking down the perilous path of losing our identity.”

When Shih returned to Taiwan in 1965, the two began working closely together. He founded the Chinese Youth Music Library (中國青年音樂圖書館) with funding from the China Youth Corps, and later the two co-founded the Chinese Folk Music Research Center (中國民族音樂研究中心). The expeditions were carried out under these two entities.

“Even when we make modern music, it’s imperative that these folk music traditions remain available to inspire our creations. As traditional folk music continued to be seriously neglected and destroyed, we needed to launch a movement to rescue it,” Hsu writes.

INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES

The first trip took place in January 1966, when Shih, fellow composer Lee Che-yang (李哲洋) and a German musicologist surnamed Spiegel visited Hualien and recorded nearly 100 Amis songs. In April and May, Lee made two trips to Hsinchu and documented about 20 Sasiyat tunes, a few ceremonial songs from their Pasta’ay ritual as well as several Atayal and Hakka numbers.

The collection effort intensified in May 1967, when Lee and a colleague spent a month visiting over 30 villages in Hualien and Taitung, collecting around 1,000 Amis, Puyuma and Paiwan songs. Four more minor trips were made before the major expedition that took place from July 21 to Aug. 1. The two groups detailed their findings in their journals, which were published in newspapers.

Shih’s team spent their time traversing the mountainous regions in the east. It was mostly fruitful, though Shih was alarmed at the erosion of culture in certain places — one Bunun village put on modern dances at their harvest festival, while a puppet troupe used pop music soundtracks instead of live instruments.

After a visit to Taitung County’s Orchid Island (Lanyu, 蘭嶼), the group ended their trip in Pingtung County’s Hengchun (恆春), where Shih notes that almost everyone was able to improvise a version of the popular local folk tune Thinking Back (思想起).

While the indigenous communities were mostly happy to share their music, Hsu’s team had a much harder time getting Hoklo people on the west coast to sing for them.

“They seemed to be ashamed of these rural folk songs,” Hsu writes. “They would refuse, saying they had a sore throat or they had forgotten them. It’s far more difficult to collect Hoklo folk songs than it is to collect songs by Aborigines or those of the Hakka people.

Hsu attributes this reluctance to the Hoklo people’s perception that they are the “most civilized” Taiwanese.

“The wealthier, more educated and ‘civilized’ people are, the more they despise folk songs,” Hsu writes.

Hsu notes that they would often find what they wanted in the most dilapidated places, not unlike where he discovered Chen. Hsu expressed the same sentiments of cultural erosion as Shih, lamenting the irony of hearing Aboriginal young men singing Mandarin pop songs right after they recorded traditional tunes from the elders.

He was in tears when he heard Chen wail, noting that he had finally found what he was looking for and all the hardships were worth it.

However, these expeditions were carried out on a tight budget, and in 1968 Shih lost support from the China Youth Corps after a dispute. He tried to keep the effort afloat by himself, but the movement eventually faded.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has