Dec. 30 to Jan. 5

From national security to saving paper and preserving news quality, the government always had excuses for its ban on new newspapers during the Martial Law era. Between 1952 and 1987, the number of papers in Taiwan remained the same at 31.

Whenever questioned by legislators, officials denied that the ban constituted a lack of freedom of speech, pointing out that 31 newspapers were plenty — despite the fact that government and self-censorship was rife in the publication industry.

Graphic: TT

James Soong (宋楚瑜), former chief of the now-defunct Government Information Office and currently presidential candidate for the People First Party, for example said in the 1980s that the nation did not have a newspaper ban problem.

“We have never banned newspapers from publishing,” he said. “In fact, Taiwan has 31 newspapers that publish between 3.5 million to 3.7 million copies per day — amounting to one copy per five citizens. That’s not low compared to developed and democratic countries. The government does not allow new papers, or for papers to increase their pages, to ensure healthy development of our news industry while our nation is in a period of emergency. There is already fierce competition between newspapers. Many are fighting just to survive, and could start publishing content that is not beneficial to the readers … We will not consider allowing more.”

Government propaganda ran deep, as a Global Views Monthly (遠見雜誌) survey in January 1987 revealed that 63 percent of respondents did not know that there was a newspaper ban.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Martial law was lifted later that year, and with it the ban. Starting on Jan. 1, 1988, a free for all ensued as the number of newspapers soared to 126 by the end of the year.

FREEDOM OF SPEECH?

While Taiwan had been under martial law since 1949, the first ordinance to ban newspapers was enacted in 1952, which mandated that the government control and restrict the number of publications to save resources during wartime. Other provisions limited the registration of newspapers and printing privileges, and finally a publishing law gave the government the power to censor and shut down any publication they didn’t like.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As a result, even though there were 31 newspapers, they had to follow the official rhetoric and refrain from offending the government. Despite this fact, in 1974, then-premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) still pointed to the 31 newspapers, 44 news agencies and over 1,900 publishing houses as proof that the government did not suppress press freedom.

“Most of these publications are free to express the views of the people and uphold justice. To claim that Taiwan doesn’t have freedom of speech, I don’t think that’s fair,” Chiang said.

Shih Hsin University (世新大學) founder Cheng She-wo (成舍我), who established Lihpao (立報) in July 1988 at the age of 90, disagreed with Soong and Chiang. Banning new publications only stunted competition, he said in a 1987 interview with the China Times Weekly (時報新聞周刊).

“Newspaper offices did not need to work hard, leading to a vicious circle where Taiwan’s media industry was never able to prosper and develop normally. Only when the ban is lifted, can this vicious cycle end, and readers can receive complete, accurate information.”

Cheng added that he didn’t see any negative effects of lifting the ban.

“Media monopoly can be solved with legislation … and improper speech will naturally be rejected and eliminated. Our justice system will deal with those who break the law,” he says.

As a testament to this column, the first Democratic Progressive Party chairman Chiang Peng-chien (江鵬堅) said in 1987 that he was looking forward to the transparency of information, especially “Taiwan’s modern history, which has always been treated as top-secret.”

THE AFTERMATH

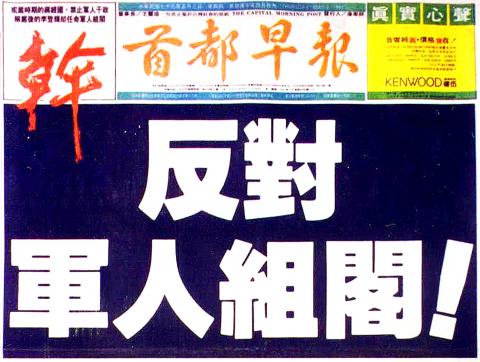

The first post-ban papers were all established by existing agencies — the Independent Morning News (自立早報) on Jan. 21, the United Evening News (聯合晚報) on Feb. 22, and the China Times Evening Post (中時晚報) on March 5. Other notable publications included the Capital Morning Post (首都早報), founded by Kang Ning-hsiang (康寧祥), a notable opposition legislator who left politics for journalism, and several children’s papers.

The lifting of the ban did not mean that papers could start printing whatever they wanted. The Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion (動員戡亂時期臨時條款) would remain in place until 1991, but with the thawing of cross-strait relations and the loosening of government control over society, readers no longer wanted to just read propaganda.

How to navigate this partially-free new world was one of the main challenges, writes Chang Hung-yuan (張宏源) in “Study of the Management of the Newspaper Industry in Taiwan After the Lifting of the Newspaper Ban” (報禁開放後台灣報業經營管理之研究).

One major effect of the ban reversal was that newspapers could now expand the number of pages — leading to greatly increased space for advertising. Chan Sheng-hsing (詹升興) writes in the study, “Development of Newspaper Advertising Five Years Before and After the Newspaper Deregulation Acts” (報禁解除前後五年報紙廣告之發展) that almost all newspapers opted to use their expanded pages for advertising. Ad revenue for the China Times (中國時報), for example, increased by nearly 63 percent in 1988.

It was a lucrative industry at first, but by the 10th anniversary of the ban’s lifting, publications were discussing the decline of the newspaper industry to television, radio and the Internet. Journalistic talent was diluted due to the sheer number of newspapers, further decreasing the quality of the reports.

By the 20th anniversary, a commemorative publication by The Foundation for Excellent Journalism Award (卓越新聞獎基金會), The Fall of a Key Power (關鍵力量的沉淪), lamented that in just two decades, the media industry had seemingly forgotten about their hard-earned press freedom and completely abandoned their journalistic values, leading to the common saying “the media is the source of social chaos.”

In the foundation’s book, many professionals write that the lifting of the ban did not make things more free — before, they were controlled by the government, now they were slaves to money, and facts were still disregarded.

Then-foundation chairman Chen Shih-min (陳世敏) writes: “The media is often a force that can upgrade or degrade a free and democratic society. We desperately need more discussion on the structure of the media and its social function to save the newspaper industry — and save Taiwan’s democracy.”

Ten years on, have things changed much?

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had