Dec. 16 to Dec. 22

A college classmate remembers Huang Tu-shui (黃土水) as someone who “only knew how to study, not displaying any indication of artistic talent and interest.” Even at the age of 20, Huang’s genius had yet to be discovered, becoming an elementary school teacher upon graduation in 1915.

But just six months into the job, he boarded a ship for Japan and made history as the first Taiwanese student at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. Five years later, he became the first Taiwanese artist to be selected to Japan’s Imperial Art Exhibition.

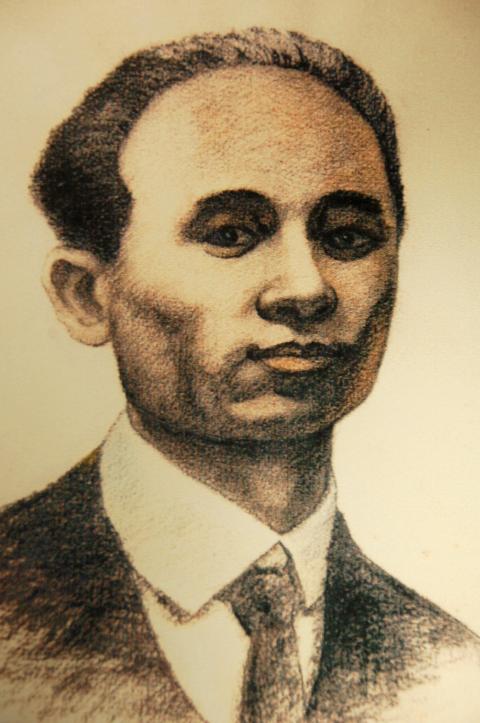

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Historica

At the height of his career, just after completing his iconic masterpiece, Water Buffaloes, he died of peritonitis on Dec. 21, 1930. It’s said that he was so engrossed in creating the massive work that he ignored his stomach pains, and by the time he went to the hospital, it was too late. He was 35.

While many of his pieces have been lost, the original Water Buffaloes still hangs in Zhongshan Hall, while replicas can be found at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts and Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts.

COLONIAL SUPPORT

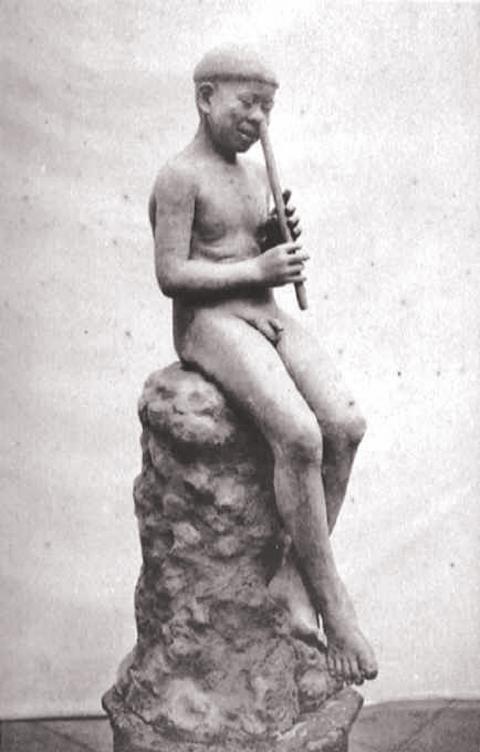

Photo courtesy of Academia Sinica

Although Huang did not receive formal training, he was familiar with woodworking because he learned it from his father and elder brother, who were carpenters. Coming from a poor family, he cherished the chance for an education and focused on schoolwork instead of making art.

Right before finishing college, a professor asked his class to turn in a craft project since the graduation exams were already over. Huang submitted a wood carving of his left hand, and at the encouragement of the professor, he made several more pieces before the semester ended.

Huang continued to sculpt during his time as a schoolteacher, and his work caught the attention of Uchida Kakichi, chief of home affairs for the colonial government who would later rise to governor-general of Taiwan. Kakichi was impressed by Huang’s skill, and recommended him for a scholarship to study art in Japan. This was unprecedented, and with the help of his college principal, Huang departed for Tokyo in September 1915.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Due to his lack of experience and training, Huang struggled at first, barely passing his first semester. His peers remembered him as an odd fellow who spent all his waking hours working on his craft, rarely socializing or resting. In a few years, people would be calling him a “genius.”

In 1920, Huang’s sculpture of an Aboriginal child made it to the Imperial Art Exhibition, rocketing him to fame in Taiwan. He would participate in the exhibit three more times over the following four years, earning him two commissions from then-Crown Prince Hirohito. When Hirohito visited Taipei, Huang was one of the few who had the privilege to a private audience.

In a 1922 article Born in Taiwan, Huang lamented that despite the island’s beauty, Taiwanese artists still focused on traditional Chinese motifs; he expressed hope that more young people would join him and create “Formosan Art.”

Photo: Chen Yi-chuan, Taipei Times

UNDYING LEGACY

Still, it was hard to make a living as an artist in those days, and Huang’s family did not have the resources. But Huang was so dedicated to his art that he would choose no other profession. His success inspired other young Taiwanese to pursue a career in art — and, like artists today, he needed a strong support network to survive.

And support he received. Taiwanese newspapers adored him, with the Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新聞) printing 156 articles on him between 1915 and 1938, starting from when he received the scholarship to go to Japan.

Photo courtesy of Lee Mei-shu Memorial Gallery

Under the support of the Taiwanese cultural elite and the colonial authorities, Huang had his first solo exhibition in Taipei and Keelung in 1927. About 10,000 people came to see the show, and Huang’s pieces were often displayed in group shows from then on to attract visitors.

Huang was reportedly so focused on his art that he was not a very sociable person, but even then he understood the importance of connections and frequently appeared at public functions by the elite. The Japanese royals and colonial authorities’ appreciation of his work also helped boost his profile.

“He built his reputation among the elite, and became a social indicator of good artistic taste. Both the authorities and the upper class frequently commissioned Huang to create self-portraits and works of art,” writes Chang Yu-hua (張玉華) in Study of Huang Shui-tu’s Artistic Accomplishments and Social Support Network (黃水土的藝術成就之養成以及社會支援網路之研究)

However, despite Huang’s prestige, he was not widely known outside the upper class. Since he died young, and since the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) did not value Taiwanese art, his name was completely forgotten after World War II. It wasn’t until the nativist movement in the 1970s that his work was “re-discovered.”

In 1974, Liberty For Education Thru Art (百代美育) magazine printed a lengthy feature about Huang. Other publications followed suit, and by 1979, Lee writes that everyone in Taiwan’s artistic circles knew of Huang. But where were his art?

It took a decade for the National Museum of History to amass about 30 of Huang’s works and host an exhibition in November 1989 — less than half of the 80 pieces shown in his posthumous exhibition in 1931.

Huang often pondered his mortality and legacy in his writings, including the following passage: “For artists, as long as the works created with our sweat and blood have not been completely destroyed, we will never die.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Toward the outside edge of Taichung City, in Wufeng District (霧峰去), sits a sprawling collection of single-story buildings with tiled roofs belonging to the Wufeng Lin (霧峰林家) family, who rose to prominence through success in military, commercial, and artistic endeavors in the 19th century. Most of these buildings have brick walls and tiled roofs in the traditional reddish-brown color, but in the middle is one incongruous property with bright white walls and a black tiled roof: Yipu Garden (頤圃). Purists may scoff at the Japanese-style exterior and its radical departure from the Fujianese architectural style of the surrounding buildings. However, the property