Dec 9 to Dec 15

As Formosa magazine (美麗島雜誌) celebrated its launch on Sept. 8, 1979 at the Mandarina Crown Hotel (中泰賓館), members and supporters of Ji Feng magazine (疾風雜誌) gathered outside.

The two publications were naturally at odds with each other — Formosa was the mouthpiece of the dangwai (黨外), or politicians who opposed the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) one-party rule, while Ji Feng was founded to counter the opposition, whom it called “Taiwanese independence mobsters (台灣獨立黑拳幫).”

Photo courtesy of Chen Po-wen

The official reason for Ji Feng’s gathering was to denounce the “traitor” Chen Wan-chen (陳婉真), who supported the dangwai from the US after being blacklisted from Taiwan for her political activities. Bringing a contingent of high school students, they yelled patriotic slogans and tried to block people from entering and leaving the hotel. Although there were skirmishes, the Mandarina Crown Hotel Incident did not descend into chaos — that would come three months later.

This event was just one of many conflicts that culminated in the Kaohsiung Incident, or Formosa Incident, on Dec. 10, 1979, when police and protesters clashed during a pro-democracy rally organized by Formosa magazine.

Much has been written about the incident and its ramifications, but everything began a year earlier, when the US announced that it would break relations with Taiwan for China.

Photo: Chu Pei-hsiung, Taipei Times

SIMMERING TENSIONS

Having made significant political gains in the local elections of 1977 — despite accusations that the KMT rigged votes — the dangwai was hoping to further its success during the supplementary elections for the national assembly and legislature.

Since opposition political parties were banned, these independent candidates formed a dangwai canvassing team in October 1978 to campaign as a group, which alarmed the government. Their collective platform included ending martial law, government censorship, the ban on new political parties and discrimination against local languages, and calling for the release of political prisoners.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The first incident broke out on Dec. 6 during a dangwai press conference, when then-legislator Huang Hsin-chieh (黃信介) changed a phrase in the national anthem from “my party” to “my people,” causing pro-KMT politicians to rush the stage.

When the US announced that it was breaking relations with Taiwan for China on Dec. 16, just six days before the vote, the government suspended the elections. They issued several warnings that any pro-independence or anti-government activities would be severely punished. But on Dec. 25, the dangwai released a public statement criticizing the KMT’s authoritarian rule and reiterating its previous demands for democracy and freedom.

A month later, the government arrested dangwai leader Yu Teng-fa (余登發), tying him and his son to a sedition case and sentencing them to eight and two years in jail respectively. Led by then-Taoyuan County Commissioner Hsu Hsin-liang (許信良), the dangwai took to the streets for the first time to call for Yu’s release. The government then shut down two dangwai publications and moved to impeach Hsu for his actions.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The dangwai continued to organize gatherings throughout 1979, but in July, the government started suppressing them by force. On Aug. 4, the police shut down the underground newspaper Chao Liu (潮流) and arrested two of its staff in a widely-publicized incident after co-founder Chen, the dangwai supporter, protested by staging a hunger strike at Taiwan’s representative office in New York.

OPPOSING MAGAZINES

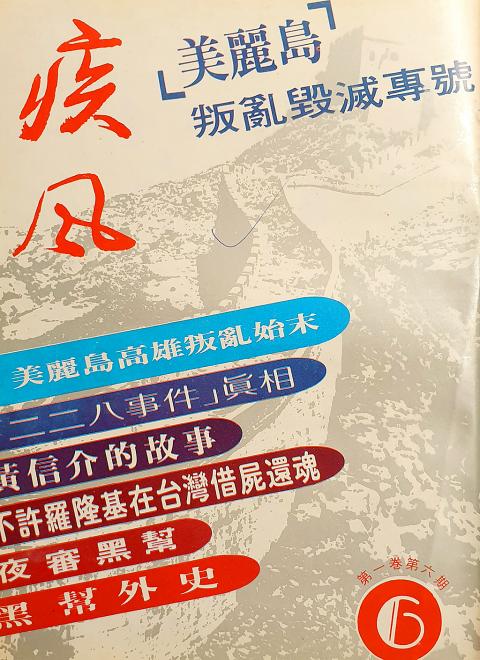

Ji Feng was founded on July 7, 1979. It slams the dangwai in its introductory statement.

“What makes us infinitely angry is that while Taiwan, Kinmen and Matsu have achieved peace and prosperity never seen in thousands of years of Chinese history… there’s a tiny countercurrent — the aspirant Taiwanese independence mobsters. They are driven by power and desire, and walk the same road as the communist bandits. They have willingly oppressed China on behalf of Westerners, using ‘democracy and human rights’ as a guise to incite violence and divide our territory and destroy our glorious achievements on this base to reclaim China… Our compatriots, it is time for the silent majority to attack these bandits! Let us unite and strike relentlessly and viciously against these demons!”

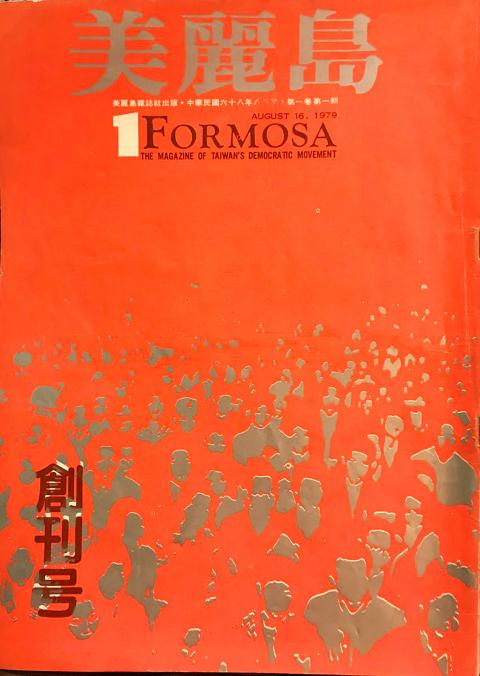

Formosa released its first edition on Aug. 16, 1979. Huang, the legislator, writes in the introduction: “Faced with national fervor toward the elections, the KMT panicked due to its political crisis [with the US]. It hurriedly stopped the elections and has been using all sorts of high-pressure tactics to destroy this tide of democracy, causing much worry and uncertainty in society over the past half-year… But democracy will not die. Long live the elections! We are encouraged by the people’s passion to participate in politics, and strongly believe that democracy is the tide of the times and cannot be stopped! This is why we have determinedly founded Formosa magazine to push forward the political movement of the new generation!”

In its third issue, the Ji Feng camp called their actions at the Mandarina Crown Hotel a “large-scale and far-reaching patriotic movement to save the country,” vowing that they would continue to take action until the “independence mobsters” were stopped.

Despite this vow, Ji Feng denied involvement when Formosa’s office and Huang’s home were ransacked by unknown attackers. Instead, they claimed that Formosa staff orchestrated the attacks themselves to gain sympathy and make the KMT look bad, in order to justify their “rebellious actions.”

In its sixth issue, Ji Feng celebrated the Kaohsiung Incident, stating: “The night of Dec. 10 is when god willed the utter destruction of these independence mobsters.”

Little would they know that today, the incident is now remembered as the turning point in Taiwan’s struggle for democracy.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she