When the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami hit Japan on March 11, 2011, it dragged out a blue-and-white sampan or wooden fishing boat, with serial number MG3-44187 and cast it adrift in the ocean.

Three years later, that same boat was found shipwrecked off the coast of Taitung. It is now slumped against the entrance to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei, where the curators of Co/Inspiration in Catastrophes (災難的靈視) have placed it as a symbol of the irrelevance of national borders when natural disaster strikes.

In a video playing in the museum, curator Huang Chien-hung (黃建宏) explains that the show’s thesis started with a question posed by his co-curator Yuki Pan (潘小雪): Why do so many natural disasters befall Taiwan’s eastern coast? The country experiences an average of 22 earthquakes a year, with 70 percent centered in the northeast.

Photo courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio

Geology aside, the curators soon found themselves up against the systems, laws and policies in place to detect and react to natural disasters, opening up the larger question of human intervention.

The resulting collection of works by 16 artists, on view at the museum until Feb. 9, examines the role of humans in catastrophic change of all kinds. They range from first responders to natural disasters to progenitors of political movements, and from victims of colonization and urban renewal to masters of their own fate.

If this all sounds very disparate, that’s exactly how it feels walking through the exhibition. While individual works contain thought-provoking nuggets, as a whole, the juxtaposition of such a wide range of topics is enough to give you whiplash. It also reduces the show’s impact.

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

‘BE WATER’

But back to the sampan. A short walk away is another boat, a “Lennon ship” created by a group of Hong Kong students and sympathizers at the Taipei National University of the Arts (TNUA). It’s less a seaworthy vessel, and more a symbol of the ongoing protest movement’s mantra to “be water” and find resilience in fluidity.

The political unrest and violence that have engulfed Hong Kong are treated here as one of the many types of human-made catastrophes, and also reflect Taiwan’s preoccupation with developments in the semi-autonomous city.

Photo courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei

Inside the museum, the TNUA students use a timeline of protest imagery and video footage to present the movement’s ideals. It’s nothing you haven’t seen on the news — until you get to a makeshift living room where the conflict has been translated into family drama radio plays.

Through headphones, characters debate inheritance, who gets to make decisions for the family and the use of violence as a way to discipline the children. Family conflict is universal, and here it becomes a way of understanding the deeply felt beliefs of the geopolitical actors.

China-watchers will also be drawn to arguably the biggest name in this exhibition, Ai Weiwei (艾未未), the Chinese artist and activist who has run afoul of Beijing’s censors for years now. But his works focus on a different part of the world entirely — migrant crossings from the Middle East to Europe, and the nowhere lands of refugee camps.

Photo courtesy of MOCA, Taipei

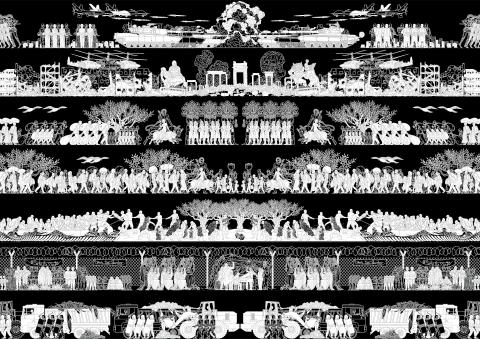

The tone is set by the wallpaper, Odyssey, which depicts caravans and boats of refugees in the style of ancient Egyptian art, giving them the gravitas of those paintings. In four documentaries, Ai presents in unflinching detail the lives of people who have fled war and poverty only to endure more suffering.

There are attempts to assign responsibility, particularly in the feature-length Human Flow, which spans some 40 refugee camps. Ai interviews humanitarians and experts, who discuss the effect of government refugee deals and policies that are never made with the refugee’s interests in mind.

That underscores the newness of refugee voices being given time and space in prestigious institutions like an art museum. It elicits empathy, and gives a sense of the immense geographical and historical scale of this flow of humanity. A mother trying to express her worries about her children’s future is overwhelmed with emotion and vomits into a metal can. A man points to the grave of his brother and shuffles through a deck of identity cards, pointing out the ones who have died.

Photo courtesy of MOCA, Taipei

The exhibition also addresses Taiwan’s own history of natural disasters. The effect that such calamities have had on Aboriginal communities is particularly pronounced, and is given appropriate attention in a few works by Aboriginal artists.

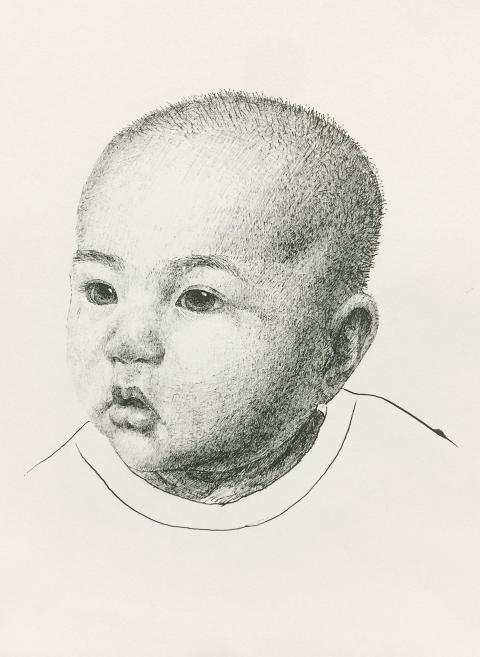

Ikong Hacii renders delicate and dignified hand-drawn portraits of people from her Sediq community, whose villages were destroyed in the eponymous Typhoon Toraji. The typhoon hit eastern Taiwan in July 2001 and killed at least 200 people.

Rukai artist Eleng Luluan and Puyuma artist collective Pakavulay use traditional weaving techniques to create sculptures that comment on the destruction and reconstruction and Aboriginal communities and cultures as a result of natural disaster, but also development and central governance.

Photo courtesy of Sachiko Kazama and MUJIN-TO Production

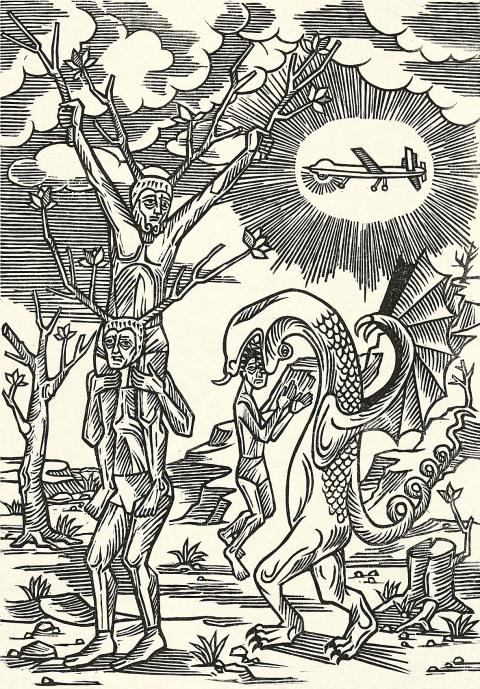

Unsurprisingly, monumentalizing the moment of destruction and the process of reconstruction is a repeat motif in this exhibition. The most literal depiction of all comes from Tseng Hsiang-chi (曾湘淇), whose paintings show demonic creatures looming over apocalyptic landscapes, confronted by small human figures bathed in light.

The scenes recall Tiananmen’s Tank Man, or the Charging Bull and Fearless Girl statue on New York’s Wall Street. In the artist’s words, they are meant to celebrate the heroes who carry out rescue and reconstruction missions. But the exhibition does its best work when it stays away from such valorization, and goes deep into the trauma and discomfort of catastrophic change.

Photo courtesy of MUJIN-TO Production

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the