Dec. 2 to Dec 8

In March 1980, almost everyone in Taiwan knew about the foreign “big beard” (大鬍子) whom the major newspapers just couldn’t stop talking about. He was allegedly involved somehow with a brutal incident that rocked society — the murders of former politician and activist Lin I-hsiung’s (林義雄) mother and twin daughters on Feb. 28, 1980.

This “big beard” was J. Bruce Jacobs, an American-born Australian academic who first came to Taiwan in 1965 as a postgraduate student, going on to become a renowned expert in Taiwan studies. After the murders, Jacobs was placed under police protection and barred from leaving the country for three months in an absurd debacle that he details in his his 2016 book, The Kaohsiung Incident in Taiwan and Memoirs of a Foreign Big Beard. The book is dedicated to the victims, with whom Jacobs was friendly with.

Photo: CNA

Jacobs was put on a government blacklist and couldn’t return to Taiwan until 1992; he made his final visit in November last year when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs awarded him with the Order of Brilliant Star with Grand Cordon for his contributions to democratization and human rights in Taiwan.

Jacobs died in Melbourne last Sunday at the age of 76. The Lin family murders remain unsolved.

FRIEND OF THE OPPOSITION

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

According to his book, Jacobs was interested in totalitarian regimes during college and planned to become a Soviet specialist. He signed up for an Oriental Civilizations class thinking, “I should know something about Asia and be done with it,” but soon became fascinated with China.

When he graduated in 1965, the Cultural Revolution had just begun and traveling to China was impossible. So like most academics interested in that country, Jacobs headed to Taiwan. He studied Chinese for a year in Taipei, and later returned to conduct a field study of local politics in rural Taiwan, where he grew used to “swearing rather automatically” in Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) like the best of them.

As Jacobs rose up in the academic ladder, he kept returning to Taiwan. In 1979, he was hoping to meet with the newly appointed Government Information Office director-general James Soong (宋楚瑜). Soong was busy, and meanwhile he became friends with many dangwai (黨外, “outside the party”) politicians opposing the authoritarian Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), including Lin.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The dangwai politicians were angry at the government. While they were allowed to run in elections since 1969, the KMT suspended all electoral activities in 1978 in response to the US cutting relations with Taiwan. Lin was one of the core members of the dangwai magazine Formosa (美麗島), and the magazine’s headquarters were located above his home.

When Jacobs returned a year later, many of these friends, including Lin, were in jail over the Kaohsiung Incident, during which the military police clashed with democracy protesters during a rally organized by Formosa. He spent time with the families of the imprisoned, often visiting Lin’s house with other Dangwai members and playing with his daughters.

BANNED FROM TAIWAN

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

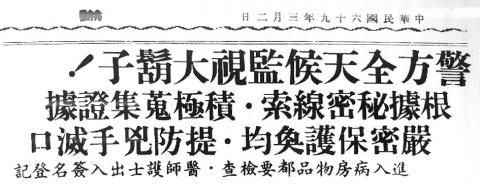

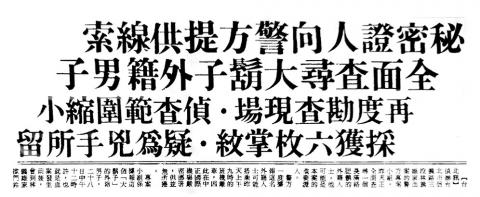

Jacobs found out about the murders that evening at the hospital where Lin’s wife and surviving daughter were staying. The next day, the United Daily News became the first outlet to call him “big beard” in the page 3 headline, “Secret witness gives police clue, full-scale search for big-bearded foreign male.” Jacobs writes that he had visited the Lin house the previous day around 6pm and nobody answered the door. The article claimed that he visited around noon, shortly before the murders happened.

The next day’s headline was “Police monitor big beard around the clock,” revealing that he had a PhD from Columbia University — essentially giving away his identity. Insisting that he had nothing to do with the murders, Jacobs agreed to be placed under 24-hour police protection. But the police continued to question him, the newspapers continued to update on the big beard’s alleged involvement, and he learned that he was barred from leaving Taiwan as an important witness to the case. He spent most of his time in a room in the Grand Hotel, or in court.

The bizarre and convoluted details of the next three months can be found in Jacobs’ book. Finally, on May 21, he was allowed to leave Taiwan after late national policy adviser Tao Pai-chuan (陶百川) brought the issue up to then-president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國). Once he was free from the grasp of Taiwan’s security agents, Jacobs “broke down and cried.”

Jacobs stayed away from Taiwan for the next 12 years. By 1992, he was teaching at Monash University in Australia and served as a member of the Australian-Chinese Council. Taiwan’s representative to Australia, Francias Lee (李宗儒), had been trying to get Jacobs to the country for years; he finally succeeded in securing a visa in June 1992 after telling the authorities Jacobs had become “too important to ignore.”

Taiwan was a very different place by then, and Jacobs noted the advances in democratization and the “surge of Taiwanese consciousness sweeping the island.” But the police were still following him around. This happened again during a visit in 1993, and his subsequent visa requests were often denied. After Jacobs brought up the issue when he met then-president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) in 1995, he was able to obtain visas with no issue. In 1996, Jacobs observed Taiwan’s first direct presidential elections.

However, Jacobs still noticed that he would be stuck at the immigration desk for at least half an hour every time he entered Taiwan. This continued until Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president in 2000 — he was pretty much free to come and go without hassle after that.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the