Nov. 25 to Dec. 1

Olav Bjorgaas’s dream to serve as a medical missionary in China was dashed when the Chinese Communist Party expelled the Norwegian Mission Alliance (NMA) in early 1949.

The 23-year-old had worked toward this goal since the end of World War II, and was four years away from completing the schooling required for the task. Dejected, he considered heading to the former Dutch colony of Indonesia instead.

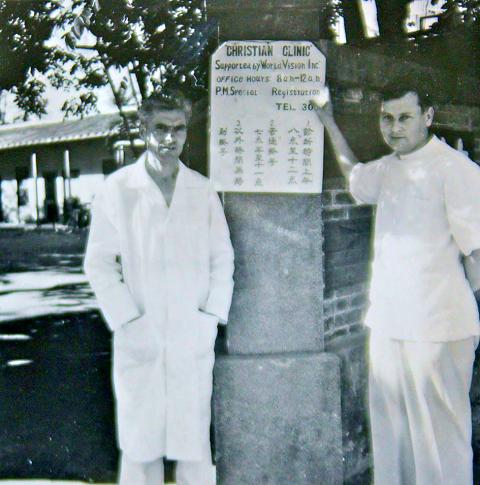

Photo: CNA

Meanwhile, the NMA staff were stranded in Hong Kong when they received a telegram from one of their long-time missionaries, Guri Odden, who was deported several months earlier. She informed them that she was on a small island 180km from China, where the Presbyterian Mackay Memorial Hospital welcomed the NMA to continue their work there.

In the spring of 1949, Bjorgaas received the news: after finishing his studies, he would be heading to this small island called Formosa.

Bjorgaas would make Taiwan his home for most of the next 28 years, caring for countless leprosy, tuberculosis and polio patients. He also co-founded Pingtung Christian Hospital and the Victory Home, which originally housed polio patients and now serves developmentally disabled children and adults. He died in his hometown of Stavanger, Norway on Nov. 15.

Photo courtesy of Geir Fotland

DAYS AT LOSHENG

Just a month after graduating in January 1954, Bjorgaas said “I do” twice — first to his then-fiancee Kari and then to the NMA. On May 23, the couple boarded the SS Venus, arriving in Keelung on July 7. He was greeted by Kristoffer Fotland of the NMA, who had left his job at Mackay Memorial Hospital and set up a mission in Hsinchu. Odden had moved on to do similar work in Japan.

There were four other NMA members in Taiwan at the time, “scattered across the island without a job description, they would decide what to do through personal connections they made,” states Bjorgaas’s biography by Bjorn Jarle Solheim-Queseth. Bjorgaas thought he would be working at Mackay, but plans had changed since Fotland’s departure. The couple decided to spend their first two months learning Mandarin.

Photo courtesy of Geir Fotland

Bjorgaas had seen his first leprosy patient during a stop in Hong Kong, and was “drawn to this strange and mysterious disease,” writes Solheim-Queseth. He expressed interest in treating such patients in Taiwan, only to be told that there were already two Western doctors on the task. But by the time he arrived, one had died and the other had suffered a stroke.

A month after Bjorgaas’ arrival, American doctor Joseph Leyburn Wilkerson came calling on behalf of Lillian Dickson. Nicknamed “Typhoon Lillian,” Dickson first arrived with her husband in 1927; they returned after World War II and she established Mustard Seed International to provide various public health services.

The job was exactly what Bjorgaas wanted — to help out at the severely understaffed Losheng Sanatorium (樂生) for lepers in today’s Sinjhuang District (新莊) in New Taipei City. Back then, it housed more than 1,000 patients. Bjorgaas agreed immediately.

Photo courtesy of Geir Fotland

It was not an easy time, as the patients did not trust him. He was too young, didn’t speak Mandarin and practiced a different religion. In addition, many Westerners had already passed through here and vowed to help, few fulfilling their promises. Morale was low, residents were in constant pain and suicide was common. About 350 patients also had tuberculosis, which Bjorgaas also tried to cure.

After witnessing numerous suicides, and with little progress made with the residents, Bjorgaas started questioning why he came to Taiwan. Things only changed when he saved a choking patient’s life by personally sucking the phlegm out of his breathing tube with a catheter.

EXPANDING OPERATIONS

The couple stayed at Losheng until 1956, and then moved to Pingtung to take over a clinic for tuberculosis patients that had lost its American doctors. Housed in a dilapidated granary, it was the only Western medical facility in the area. They later established a leprosy clinic near Kaohsiung to help patients who were often in hiding due to stigma and fear of being forcefully quarantined by the government.

With the help of two former Losheng residents, they tracked down a 15-year-old boy hiding in a photography darkroom, a man lying in a closet with flies on his open wounds, and many more. They never used the word “leprosy” and didn’t ask for patient names; the number of patients grew quickly.

Bjorgaas later moved the Pingtung clinic into a large Japanese-era mansion he was able to rent for cheap, naming it the Pingtung Christian Clinic. Soon, Fotland joined him. In addition to clinic work, they took turns heading into the mountains to search for patients in isolated villages. In its first year, the Pingtung Christian Clinic treated more than 26,000 people, and by 1958, it included a sanatorium for children suffering from tuberculosis.

They also began treating polio patients after an outbreak that year. In 1962, he imported Taiwan’s first polio vaccines from the US, administering them for free to 4,000 children. A year later, he established a factory to build crutches, and also worked with the Pingtung County Government to establish special education classes for disabled elementary school students.

The missionaries vowed to stay when the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis broke out in 1958 — Fotland wouldn’t let the communists drive him away a second time. In 1959, Bjorgaas headed back to Norway to work and raise funds for his future hospital. He continued to expand the facilities in Pingtung, and in 1963, the Pingtung Christian Hospital opened its doors.

Despite his success, Bjorgaas was not popular with his colleagues. They said he was stubborn, disagreeable and only cared about Taiwan’s sick and poor with no regard for his fellow missionaries. The NMA removed him from the Pingtung hospital in 1967, dispatching him to a leprosy clinic in Kaohsiung. After a brief stint away from Taiwan, Bjorgaas returned to Pingtung in 1974 after his main detractors departed.

Bjorgaas also spent time in other NMA areas such as Vietnam, South America and Haiti, and the couple officially moved back to Norway in 1982, although they would still visit Taiwan from time to time.

In 1991, Bjorgaas finally made it to China for a stint at the Sino-German Clinic in Beijing, fulfilling his dream 37 years later.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the