When I go on a long bike ride, it’s not just to get some exercise. Along the way, I stop at places that bloggers or local governments deem to be “tourist attractions,” but which to me don’t sound as if they deserve a special excursion. Oftentimes, my instincts are proved right. Within minutes of arrival, my bicycle is unlocked and my helmet is back on my head.

But sometimes I’m pleasantly surprised. A couple of weeks ago, I halted at the Liu Family Ancestral Mansion (劉家古厝), in Liuying District (柳營區) in the northern third of Tainan City, and more than an hour passed before I resumed my ride.

I’d first heard about the mansion well over a decade ago, but hadn’t bothered to take a look, in part because other districts around Liuying — such as Yanshui (鹽水) and Houbi (後壁) — always seemed to offer much more in the way of history and scenery.

Photo: Steven Crook

I didn’t realize until I arrived that there are actually two landmark buildings, separated by a lane wide enough for cars. If you’re standing on Jhongshan West Road (中山西路), the single-story complex on the left of the lane is the Liu Clan Shrine (劉家宗祠). The two-floor building on the right is the Liu Chi-hsiang Art Gallery and Memorial Hall (劉啟祥美術紀念館).

Given the thoroughly traditional layout of the former and the obvious interwar appearance of the latter, it’s no surprise that more than half a century elapsed between the building of the two.

The shrine complex and its grounds cover about 800 ping (2,644 m2). Construction was commissioned in 1867 and completed within four years. Much of the work was done by Fujianese artisans, and many of the materials were shipped in from the mainland. The roof tiles, however, were fired locally.

Photo: Steven Crook

A brick wall surrounds the front courtyard, and the iron gates facing Jhongshan West Road were locked. If it weren’t for a passerby, I might never have gotten inside. He told me one of the side-doors is usually open, and that it’s fine to take a look.

I found the entrance, which was unlabeled but wedged open. There was no indication of regular opening hours, nor even a handwritten note with a phone number for people to call if they’re seeking access. Perhaps, like some similar ancestral halls I’ve been to in various parts of Taiwan, it opens and closes entirely at the whim of whichever clansman happens to be taking care of it that week.

Within, there are 16 chambers, some of them quite spacious. A few were locked. Of the others, all but three were empty. One contained a pile of roof tiles. Another stored dozens of plastic stools.

Photo: Steven Crook

The central chamber housed the ancestral altar, around which at least 65 ancestral tablets were arrayed. (I couldn’t get close enough to be sure I’d counted all of them). Even if most of the compound seems to be gathering dust, the censer on the altar is kept smoldering. A wall next to the altar is given over to a family tree that covers the first 12 generations of the Liu clan to settle in the area. In keeping with the patrilineal customs of yore, only sons are listed.

The shrine is photogenic, yet lacks its original symmetry. There used to be two flagpoles in the front courtyard. The one on the right, if you face the shrine from Jhongshan West Road, was destroyed by a lightning strike many decades ago. The surviving flagpole, which is wooden and 15m in height, honors Liu Ta-yuan (劉達元). In 1852, he obtained a juren (舉人) degree in the examinations that governed civil-service appointments in the Qing Empire, of which Taiwan was then part.

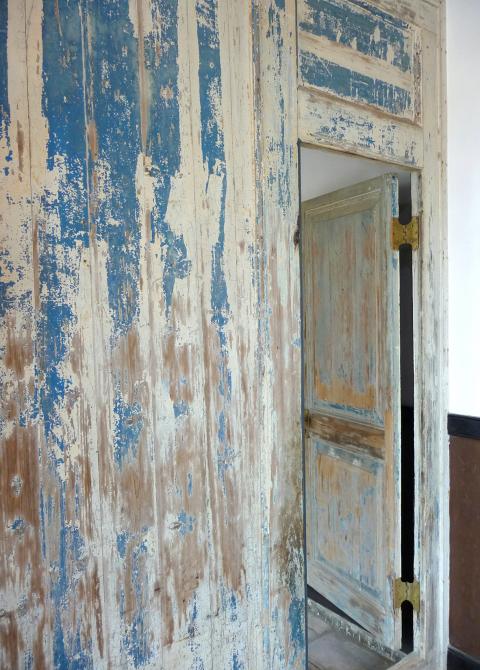

The house where Liu Chi-hsiang (劉啟祥, 1910-1998) once lived was extensively renovated with the help of the Tainan City Government and opened to the public late last year. Unoccupied and neglected for some years, it was in a pitiful state.

Photo: Steven Crook

This project involved first reconciling the views of the 17 individuals between whom land ownership is divided, then two years’ of careful restoration at a cost of NT$23 million. The end result is very attractive. Exploring the interior, I thought: “Now this is a house I’d love to live in” — then realized there wasn’t a single bathroom. Well-to-do families like the Lius would have had servants to empty their chamber-pots, and bring them buckets of hot water whenever they wanted to wash.

Liu Chi-hsiang was one of the most notable painters of his generation. He studied first in Japan, then in 1932 he sailed for France. Accompanied by Yang San-lang (楊三郎) — who went on to become an even more famous artist — Liu arrived in the French port of Marseille. There they were met by one of Yang’s relatives, and the three men walked all the way to Paris.

By the autumn of 1935, Liu was back in Taiwan. For the rest of his life, he moved between Liuying and Kaohsiung. He married, was widowed, and married again. He sold paintings, taught art and cultivated an orchard. The art gallery displays facsimiles of more than a dozen of his works, which were heavily influenced by impressionism. If you’re carrying a smartphone, you can listen to a free online English-language audioguide.

Photo: Steven Crook

Liu used the single-story building in front of the residence as a studio. It’s now a coffee-shop that sells snacks and desserts. The coffee-shop, like the art gallery/memorial hall, is open from 10 am to 6 pm, Wednesday to Sunday. The address is 112 Jhongshan West Road Section 3, Liuying District, Tainan City (臺南市柳營區中山西路三段112號).

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, and author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide, the third edition of which has just been published.

Photo: Steven Crook

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she