Oct. 7 to OCT. 13

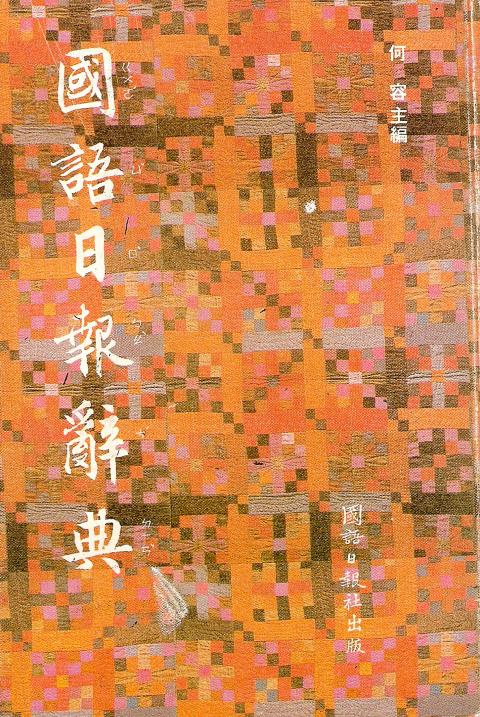

Hsieh Tung-min (謝東閔) didn’t think too much when he received a dictionary in the mail. But as soon as he opened it, the book exploded, shattering the windows in his room and collapsing the ceiling. He was rushed to the hospital, where the doctors amputated his left hand and his right ring finger.

It was Oct. 10, 1976, and Hsieh had just returned home from observing the Double Ten celebrations and inspecting the newly-completed Huazhong Bridge (華中橋).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“I did not feel hateful, I just lamented that I wasn’t careful enough. What I cared about most is that our stable and prosperous base to reclaim [China] did not suffer any more damage,” Hsieh writes in his memoir. “I did not think of resigning because that would make me look like a coward. Also, I still had many aspirations.”

Hsieh wasn’t the only government official to be letterbombed. China Youth Corps chairman Lee Huan (李煥) also lost a finger, while General Huang Chieh (黃杰) narrowly escaped after a warning from Lee. It was later found that the culprit was Wang Sing-nan (王幸男), a Taiwanese businessman residing in the US.

Two years later, Hsieh became Taiwan’s vice-president under Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) — the highest post ever achieved by a Taiwan-born politician at that time after more than three decades of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

While Hsieh was part of Chiang’s policy to promote more Taiwanese politicians, including former president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝), the independence activists saw him as a traitor for working with the authoritarian government.

‘HALF MOUNTAIN’

Hsieh was what they called a banshan (半山, “half mountain”) in those days — a Taiwanese who spent significant time in China and returned with the KMT after the Chinese Civil War. Born in Changhua County in 1908, Hsieh witnessed Japanese brutality towards Taiwanese from a young age. In his memoir, he details the various injustices that led him to resent the Japanese and strongly identify with the “motherland” of China.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Tired of being treated as a second-class citizen, Hsieh headed to Shanghai to study when he was 17 years old, vowing not to return home as long as the Japanese ruled Taiwan. In 1930, during his last year of university, Hsieh joined the KMT after deciding that its “Three Principles of the People” fit China’s needs the best.

During World War II, Hsieh was a key part of the KMT’s preparatory efforts to spread its influence in Taiwan once the Japanese surrendered. At the National Assembly in May 1945, Hsieh urged the KMT to use as many Taiwanese as possible once they took over in order to connect better with the populace; obviously that suggestion was not heeded. After 20 years in China, he finally arrived home on Oct. 24, 1945.

Hsieh had planned to assist the KMT culturally by teaching Mandarin and promoting Chinese culture and history, but governor-general Chen Yi (陳儀) ordered him to serve as Kaohsiung County’s first commissioner.

It seems that Hsieh was a capable official who genuinely cared about the people and desired to improve the nation as he rose through the ranks. But given his position and the year the memoir was published (1988), it completely follows the official narrative of that time: Taiwan was a democratic nation, and the White Terror didn’t exist. The 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising in 1947, is never mentioned.

One of Hsieh’s lasting contributions was advocating vocational education — leading to the birth of today’s National Taiwan University of Sport, National Taiwan University of Arts and Shih Chien University, which he personally founded in 1958 as Shih Chien School of Home Economics.

To boost the economy, Hsieh promoted the home-manufacturing movement under the slogan “turn your living room into a factory,” leading to many products worldwide carrying the famous “Made in Taiwan” stickers.

POLAR OPPOSITES

Chiang’s choice of Hsieh as his first vice-president is seen as the beginning of his tendency to promote Taiwan-born politicians. But Hsieh’s idealistic view of harmonious relations between Taiwan-born and Chinese-born citizens seemed rather delusional — again, this could just be official speak. Regarding his “bid” for vice-president (both he and Chiang ran unopposed), he writes in his memoir:

“Some of my friends were worried that since I was born in Taiwan, it would be difficult for me to garner the support of National Assembly members from different provinces. I don’t think that should be a concern. Everybody who lives on this [island] originally came from China … Over the past 30 years, the ones who came first and those who came after 1945 have fully integrated, working together to build Taiwan as a prosperous paradise to propagate the Three Principles of the People. There is absolutely no ‘us’ and ‘them.’”

Any form of violence should not be condoned, but it’s important to consider the point of view of Wang, the man who sent the bomb. Born in 1941, Wang attended the Republic of China Military Academy and fully believed in the KMT propaganda until he was discharged in 1970. He subsequently headed to the US to study. Free of government censorship, he started learning about the 228 Incident and the attempt to assassinate Chiang, and questioned his unwavering belief in “reclaiming the mainland.”

“Under the KMT, I believed that anybody who opposed the government was a bad person. I was taught that the KMT took care of the people and was a party that showed great leadership. Only when I arrived in the US did I realized that not only was I lied to, I was lied to for so many years. I became very angry,” Wang says in an oral history collection of independence activists published by Academia Sinica.

Regarding his bombing attempt: “I felt that reform would never come in Taiwan, and that a more extreme revolution was needed,” claiming inspiration from incidents in Palestine and Northern Ireland. “I wanted to let the KMT know how angry the Taiwanese were.”

Why did he target Hsieh? “He is a Taiwanese, and he held such a high position in the government, but he never spoke out on behalf of the Taiwanese. That’s why I chose him.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she