As a standalone, Detention holds its own as an easily-understandable, horror-tinged psychological drama about government oppression during the White Terror era. Set in 1962, it will be applauded for brutally displaying the horrors of life under martial law, when one could be jailed and even executed just for reading and disseminating banned books, and one misstep could cause dozens to disappear.

It’s a very likeable film, with atmospheric and layered visuals that are chilling but not downright terrifying. The plot offers just enough supernatural and horror elements yet mainly focuses on the dramatic and emotional, and it lays bare and bloody the period of authoritarian rule.

Many Taiwanese have family stories regarding the White Terror that they kept hidden, as it remained a taboo topic until recent decades. Those on the other end of the political divide will undoubtedly hate the film and claim that it is exaggerated to demonize the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

Photos courtesy of 1 Production Film Company

It’s inevitable that a movie version of Detention would be made after the game took the Internet by storm in January 2017, even becoming a big hit overseas after it became available on the Steam platform.

It was a big-name production from the start. Former actress Lee Lieh (李烈), whose production credits include 2010’s hit Monga (艋舺) and 2015’s The Laundryman (青田街一號), co-produced with Aileen Li (李耀華), who coordinated the shooting in Taipei of Luc Besson’s Lucy as well as John Woo’s (吳宇森) The Crossing (太平輪).

Director John Hsu (徐漢強) became the youngest director to win a Golden Bell in 2005, and most recently created the acclaimed VR movie Your Spiritual Temple Sucks (全能元神宮改造王), which won Best Innovative Storytelling at last year’s World VR Forum in Switzerland.

Compared to the video game by Red Candle Games that the movie is based on, something feels missing. Though impossible to reproduce a game that takes hours to play on the big screen, the film seems to have simplified things just a bit too much, eschewing the slow-building suspense and subtlety that made the game such a joy to play.

In the game, players infer the essence of the era by finding evidence — patriotic writings on the wall and a student handbook that calls for students to “rat out anyone who may be pro-Communist or show signs of treachery.” Through tackling puzzles and gathering evidence, what really happened to the school is pieced together.

In the movie, everything is handed to the audience from the opening scene, and the bulk of the story takes place as real-life flashbacks instead of in the haunted school. As a result, the suspense suffers, as there is little mystery-solving by the characters. It’s understandable that the director took a different approach, focusing on the human aspect and exploring how people behave and handle their desires under a strictly controlled society.

The result still works as a solid psychological piece featuring a love-triangle that may even dig deeper into the human psyche than the game. It’s just not much of a horror or mystery film, which seems to be what many were expecting.

While it’s already obvious enough that the game is set in the White Terror era, the movie seems to amplify the elements to the point that it seems too intentional.

Taiwan was no paradise in the 1960s, and the government did do terrible things, but it wasn’t a bleak 1984-esque society where there was no hope or happiness. Despite this, the movie mentions very little of the politics that created such an environment.

Probably the most disappointing difference from the game is that the traditional Taiwanese elements that really gave Detention its unique flavor are mostly removed, save for a one hand puppet that appears in a few scenes.

In the game, for example, characters are attacked by hungry ghosts, whom the player avoids by placing a bowl of rice with incense sticks on the ground and walking away while holding their breath. In the film, the only monsters are military police with mirrors for faces.

The soundtrack also resembles more of a standard suspense film than the original, which samples religious ritual music.

Nevertheless, it’s the kind of film that will actually draw Taiwanese audiences away from Hollywood blockbusters, and will likely become one of the most popular domestic films of the year. That’s what Taiwan needs if it is to continue growing its fast-improving cinema industry.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

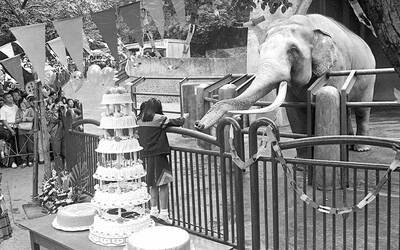

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

Mother Nature gives and Mother Nature takes away. When it comes to scenic beauty, Hualien was dealt a winning hand. But one year ago today, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake wrecked the county’s number-one tourist attraction, Taroko Gorge in Taroko National Park. Then, in the second half of last year, two typhoons inflicted further damage and disruption. Not surprisingly, for Hualien’s tourist-focused businesses, the twelve months since the earthquake have been more than dismal. Among those who experienced a precipitous drop in customer count are Sofia Chiu (邱心怡) and Monica Lin (林宸伶), co-founders of Karenko Kitchen, which they describe as a space where they