Sept. 23 to SEPT. 29

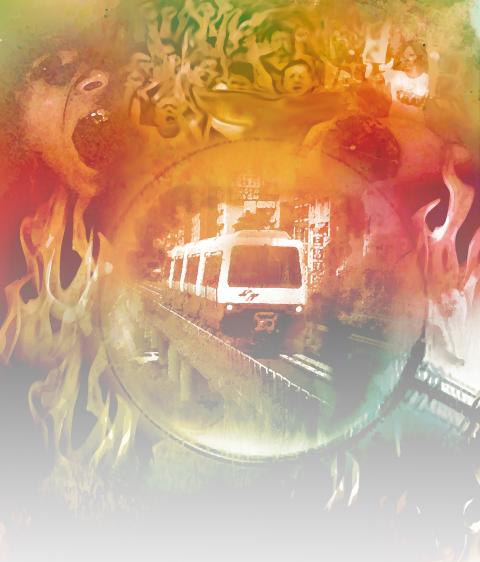

Around 5:50am on Sept. 24, 1993, a Taipei MRT car burst into flames during a test run. It took eight firetrucks 20 minutes to put out the blaze, leaving a completely charred interior and destroyed wheels. Then-Department of Rapid Transit Systems (DORTS) head Lai Shih-sheng (賴世聲) apologized to the public on behalf of French contractor Matra, and asked the company to stop all testing.

This was the second time in five months an MRT car had caught fire. A blaze on May 5 earlier that year had destroyed two cars during manual driver training, causing an estimated NT$80 million (US$2.5 million) in damages. Up until that point, DORTS had planned to open the MRT line to the public on August 2. That plan was pushed back after the incident.

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

Exactly a year after the Sept. 24, 1993 fire, a tire exploded during another test run. The three Taipei City mayoral candidates Chao Shao-kang (趙少康), Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) and Huang Ta-chou (黃大洲) arrived at the scene, with Chao and Chen demanding that all testing of the MRT system be stopped until the matter had been fully investigated.

Taipei residents may take the MRT system for granted these days, but these incidents were just a portion of what made the transport system the source of much public discontent in its early days. It would take until March 28, 1996 for the system to finally open to traffic.

ROUGH BEGINNINGS

Construction on the Muzha Line (today’s Wenhu Line) began in December 1988. When it finally opened to the public, it covered 12 stops over about 10km from the Taipei Zoo to Zhongshan Junior High School.

The line was originally supposed to open in December 1991, but suffered a series of delays. According to the book The MRT White Papers (捷運白皮書) by Liu Pao-chieh (劉寶傑) and Lu Shao-wei (呂紹煒), one major issue was that construction on all six lines began simultaneously, making it difficult to supervise. Since the nation had no prior experience with an MRT system, starting all six lines together also meant there was no chance to learn from mistakes.

The first issue was land expropriation; the conflict grew violent as DORTS staff, including former chief Chi Pao-cheng (齊寶錚), often ended up with bruises and scratches after negotiations.

This resulted in a surreal situation where government workers spent all night counting ducks to compensate farmers who would lose their land. Residents living in what is now the Nangang Depot even doused their village with gasoline and brandished gas tanks, as if prepared to fight to the death.

After much bureaucratic drama and controversy about prices and shady deals that involved gangsters and corrupt officials, construction of the line finally commenced. But its quality remained in question despite the exorbitant budget. The public was initially excited for the MRT, but grew disillusioned with each negative news report.

As a sidebar to an article about the May 5, 1993 fire, United Daily News printed a list of some mishaps during the MRT construction dating from 1990, mostly entailing structural issues such as collapsed retaining walls and cracked beams. In January 1993, a fuse was blown in one of the cars in the depot, frying the circuit board.

But the worst was yet to come.

EVERYTHING GOES WRONG

The May 5, 1993 fire took place during manual operation training — the system was automated, but drivers needed to learn how to drive the train in case of an emergency. Investigations showed that the fire was caused by friction between the wheels and the rails due to a jammed brake. The authorities were baffled, as the same system was used in many Western countries without incident.

Public confidence in the MRT’s safety plummeted, as even the engineer who tested the car told the press about his concerns about the system. On May 16, Lai announced that DORTS would push back the opening date to February 1994.

Matra identified a problem with one of the brake’s components as the cause of the fire, and announced that it had replaced the malfunctioning chip. After working through other technical malfunctions, test runs resumed in mid-August 1993.

In early September, witnesses reported seeing sparks on the rails when the train passed by. The massive fire on Sept. 24 was caught entirely on camera by Taiwan TV (TTV, 台視), and the public watched the footage in horror. It was found that the cars caught fire because the system was originally designed for two cars, but Matra had increased it to four cars to fit DORTS’ needs.

Lai resigned in October. To add insult to injury, Matra and DORTS became embroiled in a battle over construction delays and other mishandlings, and DORTS was initially ordered to compensate the French company NT$1 billion (US$32 million). The case dragged on until 2005, with Matra prevailing and the amount surging to NT$1.6 billion (US$51 million).

In June 1994, a report found that 92 percent of the line’s cap beams were cracked. After handling the issue, DORTS still tried to make its once-again delayed opening date in August.

But after failing a comical number of inspections, from air conditioning and door malfunctions to a derailing on Aug. 31, there was no way the goal would be met. A typhoon hit the next day, causing a system malfunction and serious leakage in the stations and depot.

“Everything that could go wrong went wrong,” write Liu and Lu. On Sept. 3, then-Taipei Mayor Huang announced that the MRT’s opening date would be delayed for the fifth time.

LONG-AWAITED OPENING

After years of bad press, it was almost a miracle when the Muzha Line carried its first passengers on Feb. 27, 1996.

On that day, it ran for four hours at no charge, with 15,164 people using the service. The mood was festive as people seemed to have forgotten about the previous incidents, despite protesters at the station entrances handing out flyers and asking people to be careful with their lives.

This test period lasted for a month, attracting 1.8 million passengers without incident. The line officially opened to great fanfare on March 28 later that year.

But problems continued. Matra pulled out of Taiwan two months later, leaving DORTS to its own devices. Then-Taipei Mayor Chen uttered his famous catchphrase: “If Matra won’t pull, we’ll pull it ourselves” (馬特拉不拉, 我們自己拉; the last character of Matra’s Chinese name means “to pull”).

Technical issues still broke out every now and then. For example, on June 14, 1996, lightning struck the depot, causing all trains to stop in their tracks. Two of the four trains were suspended between stations, and it took an hour for passengers to evacuate via the tracks.

More than two decades later, it’s hard to imagine life in Taipei without the MRT. But it seems that this troubled history of the MRT’s beginnings has been forgotten.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry