Sept. 9 to Sept. 15

At 9am on Sept. 9, 1945, military representatives from the Empire of Japan and the Republic of China (ROC) assembled at the ROC Military Academy auditorium in Nanjing. During the 15-minute ceremony, the generals Yasuji Okamura and Ho Ying-chin (何應欽) signed the documents that marked Japan’s unconditional surrender to China after eight years of war.

But six people were missing from the ceremony: the delegation from Taiwan, which was technically still under Japanese control.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

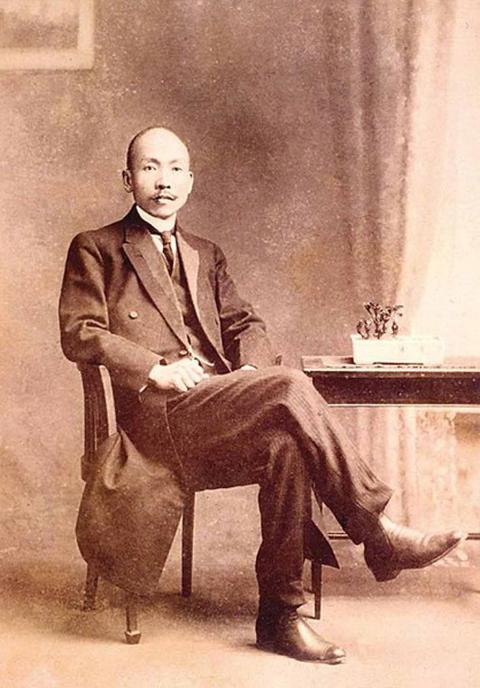

Led by Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂), head of the influential Wufeng Lin family (霧峰林家), the group of six Taiwanese intellectuals and social elites were already in Shanghai when they received the green light to attend the ceremony on Sept. 6.

However, the group was somehow “misled” by the Japanese and didn’t make it in time, according to a document held at Academia Historica (國史館). Kao Chen Shuang-shih (高陳雙適), daughter of delegation member Chen Hsin (陳炘) writes in her memoir that the Japanese officers who were in charge of their transportation stalled until they missed the ceremony, but she also mentions another version of the story where a Japanese official told the group the day before the ceremony not to attend.

The five were obviously dejected to miss such an important moment, as this was a time when Taiwanese were still excited to be rid of colonial rule and return to the “motherland” of China. The next day, Ho showed them the surrender documents, took them to the auditorium and described the ceremony.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

However, this optimism would not last long.

A REASSURING INVITATION

Japan surrendered to the Allies on Aug. 15, 1945, ending World War II. After an independence attempt that never materialized, the Taiwanese population anxiously awaited their fate.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

According to the book The Hundred Year Quest (百年追求), by historian Chen Tsui-lien (陳翠蓮), although most Taiwanese were happy to see the Japanese go and the war end, they were wary of celebrating. Nearly 200,000 Japanese troops were still stationed in Taiwan, and it was hard to tell if they were determined to resist to the end.

“Even if Taiwan was to fall under Chinese control, it was unclear when they would arrive and under what circumstances. Nobody could predict what the Chinese government would do with the Taiwanese either,” Chen writes.

Indeed, there was much animosity by Chinese toward Taiwanese as they supported the enemy during the war as Japanese citizens.

In this climate, Taiwanese leaders decided to send a group to China to connect with the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). Led by Lin, they headed to Shanghai and met with local officials and Taiwanese expatriates, but on Sept. 6 they received a direct invitation to the surrender ceremony from KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) via Ho.

The formal invitation had a reassuring effect on the population. Chen writes that the KMT did so to show good will towards Taiwan and to indicate that they would be taking over the former Japanese colony soon.

Novelist Wu Cho-liu (吳濁流) writes in his autobiographical novel The Fig (無花果), “On Sept. 6, Lin Hsien-tang and five others who had long been resisting colonial rule, finally had their efforts recognized by the central government and received an invitation to attend the surrender ceremony in Nanjing. The news spread quickly, and it was as if Lin’s honor represented the honor of the 6 million Taiwanese. Everyone was beyond excited.”

Shih Yu-min (石裕民) writes in the study, “Chiang Wei-shui before and after the 228 Incident” (二二八事件前後的蔣渭水), “Wu’s description shows that the invitation by the KMT helped alleviate concerns about the identity of Taiwanese during the transition. People were assured that they were indeed Chinese, who belonged to the victorious side.”

Taiwanese civic leaders formed the Preparatory Committee to Welcome the Nationalist Government (歡迎國民政府籌備會), delivering ROC flags to schools and offices, hanging patriotic banners and teaching locals to speak Mandarin and sing the national anthem. They also threw a joyous extravaganza in Taipei to celebrate Double Ten National Day for the first time.

UTTER DISAPPOINTMENT

After his return, Lin whole-heartedly devoted himself to paving the road for the KMT’s arrival, while avoiding taking on a leadership position in deference to Chen Yi and the incoming government. He also started eagerly learning Mandarin — quite a contrast from when he often refused to speak Japanese during colonial rule.

On Oct. 24, Lin headed to the airport to welcome Chen Yi, and made the opening speech the next day during Japan’s surrender ceremony in Taipei. A month later, he officially became a KMT member and was later chosen as one of 18 Taiwanese members of the Taiwan Provincial Assembly.

However, Chen Yi did not trust him or other Taiwanese leaders, and the KMT turned out no better than the Japanese. Lin wrote in his diary about food shortages caused by rice being sent to China to support the fight against the Chinese Communist Party. He was also dismayed by the government’s centralized and authoritarian rule. He had fought for years under Japanese rule for Taiwanese autonomy, and the KMT shut down his proposal for provincial autonomy.

He soon realized that Taiwanese were still treated as second-class citizens and that nothing had changed, and in his diary he slammed the lack of public order, the gross misconduct of KMT soldiers as well as Chen Yi’s incompetence.

In 1946, Chen Yi started a witch hunt in Taiwan for hanjian (漢奸), or “Han Chinese traitors,” who worked for the Japanese to oppress Chinese. Chen Hsin, Lin’s fellow delegate to Nanjing, was arrested as a hanjian for his alleged involvement in the 1945 independence attempt, and was detained for a month before being deemed innocent.

The people’s frustrations boiled over in February 1947, culminating in the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was brutally suppressed. Chen Hsin, who was once so eager to welcome the KMT, was taken away by the police on March 11, never to be seen again.

Lin survived the incident and was even given a government position, but he had little authority. Utterly disillusioned, he tried to quit many times but his resignation was rejected each time.

Realizing that there was little place for him in Taiwan, Lin headed to Japan in September 23, 1949 under medical leave and refused all requests to return, dying in Tokyo in 1956.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,