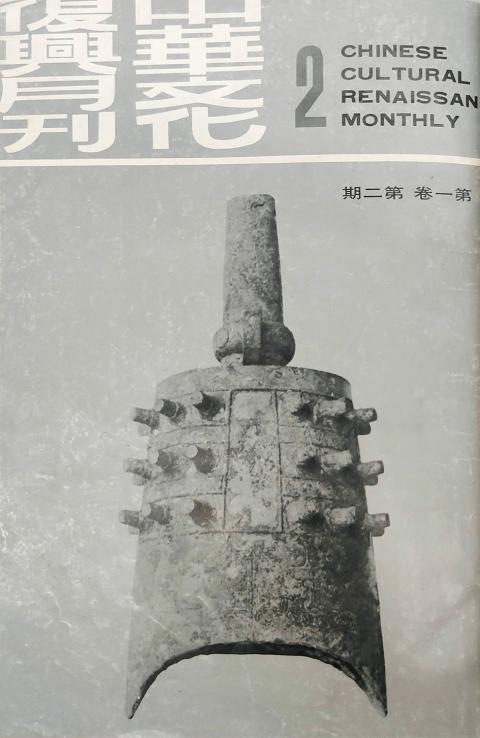

July 29 to Aug 4

While the Chinese were doing everything they could during the Cultural Revolution to destroy their cultural heritage, Taiwan launched the Chinese Cultural Renaissance Movement to do the opposite.

On the surface, the goal of the movement was to establish Taiwan’s Republic of China (ROC) government as the rightful heir and protector of Chinese culture and morals, but as Lin Kuo-hsien (林果顯) shows in “Study of the Council on Promotion of the Chinese Cultural Renaissance Movement” (中華文化復興運動推行委員會之研究), it also had a political agenda.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

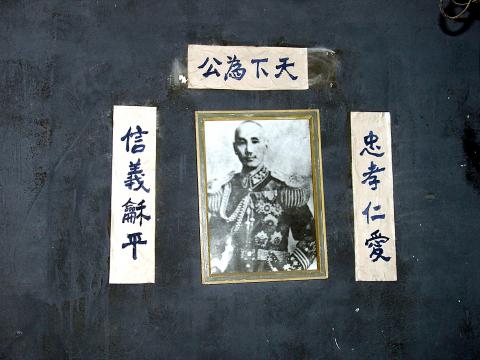

With reclaiming China pretty much out of the question, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) launched the movement as a “‘cultural counterattack’ [against China] to keep people’s spirits mobilized in order to continue its wartime provisions, and to build up the image of its leader as the successor of traditional Confucian morals to solidify the legitimacy of [KMT] rule,” he writes.

The council was established in late July 1967, with Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) presiding over 11 committees covering aspects of life including education, mass media, youth activities, women’s issues and public morals.

After many changes in structure and objectives, the council still exists today as the General Association of Chinese Culture (中華文化總會). Its mission today shows that like many organizations in Taiwan, it retains the word “Chinese” only in name: “To continue to enhance and cultivate Taiwan’s cultural power; to continue to facilitate cultural exchanges and cooperation between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait; and to strengthen exchanges between Taiwan and the international community.”

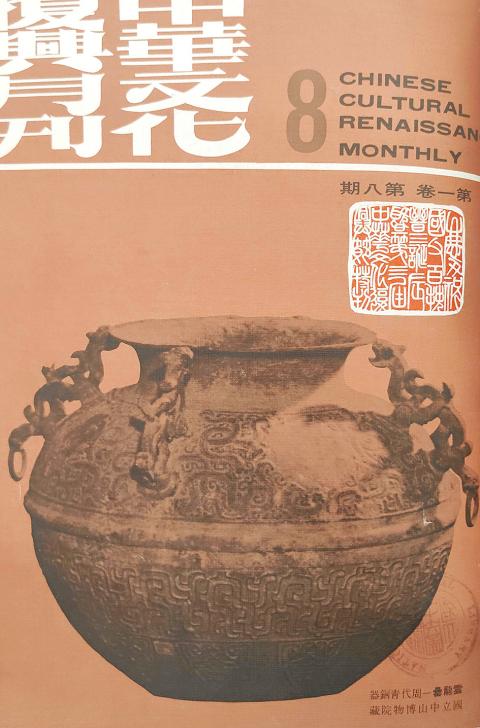

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

LEGITIMIZING AUTHORITARIANISM

Taiwan was a contradiction in the 1960s. It had obtained US support by championing free and democratic values and staunchly opposing communism — the “authoritarian and brutal” Chinese Communist Party. However, Taiwan remained under martial law, the ROC National Assembly had not held elections since 1947 and Chiang established himself as president-for-life under wartime provisions even though he had reached his term limit in 1960.

While the KMT had little hope of retaking China, it used propaganda to maintain the illusion that war could break out at anytime to justify its military rule and keep its population united and patriotic. The Cultural Revolution broke out in China in 1966, giving the KMT a perfect opportunity to launch the Chinese Cultural Renaissance Movement as a countermovement.

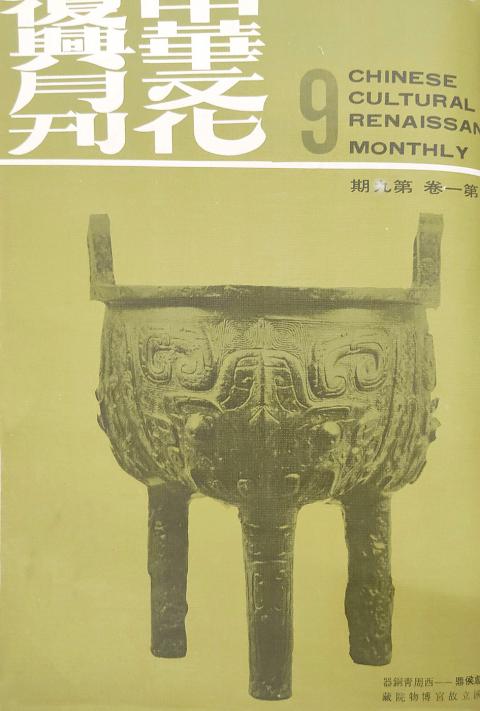

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

It was not the first not the first of its kind. The KMT had launched the Cultural Reform Movement (文化改造運動) and the Cultural Cleansing Movement (文化清潔運動) in the 1950s. These movements share the common goals of shaping the world view of its constituents by repeatedly promoting KMT founder Sun Yat-sen’s (孫逸仙) Three Principles of the People (三民主義), fostering unwavering allegiance to Chiang and carrying out the ultimate goal of defeating the Chinese communists.

The council was made up of scholars, cultural experts and a large number of high-level KMT officials. In addition to promoting traditional Chinese arts, it sought to instill the ancient “Four Principles and Eight Virtues” (四維八德) among the populace.

These ideals were heavily integrated into the school curriculum, and students participated in patriotic essay contests and singing competitions. Since many young Taiwanese had never lived in China, the association steered them toward identifying with China, which for ROC leaders included Taiwan. In this way, the students would view reclaiming “the motherland” as their own personal mission, Lin writes.

Photo courtesy of David Schroeter via Flickr

The council even claimed that Taiwan’s indigenous people came from China, and aimed to eradicate local languages in favor of Mandarin. It also established guidelines on how people should conduct themselves, ranging from respecting the flag and anthem to personal hygiene and manners such as refraining from eating while walking. It also focused on international propaganda at a time when the world’s powers started to question the KMT’s legitimacy in representing China.

POST-CHIANG YEARS

Chiang died in 1975, and his successor Yen Chia-kan (嚴家淦) took over as council head. The ROC’s standing in the world had changed dramatically — it had broken ties with the US and withdrawn from the UN while domestically it faced a proliferation of democracy protests and publications. Premier Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) was more focused on building the economy and political reform, and declined to take over as committee head when he became president in 1978, indicating that the movement’s importance had diminished.

“Chiang Kai-shek, who led both the party and the military and was also the protector of traditional morals, was irreplaceable,” Lin writes. Yen, who many saw as a lame duck president, actually remained as council head until 1990 despite not holding any political position after 1978.

The younger Chiang was less interested in promoting traditional morals, instead pushing a modern “cultural construction” (文化建設) program that would set up libraries, concert halls, museums and other institutions in every county and city. This also included setting up cultural festivals, awards and fostering talent. Chiang understood the importance of involving Taiwanese in government affairs, and his policies also paid attention to local folk culture and historic relics instead of being completely Chinese-oriented.

Nevertheless, the council continued to operate as it did before. One notable program it undertook in the early 1980s involved endorsing the plum blossom — the national flower, which blooms in cold weather — as a defining symbol of Chinese culture.

In 1991, the council was downsized and restructured as the General Association of Chinese Cultural Renaissance (中華文化復興運動總會) with then-president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) as head. While the mission was still to promote Chinese culture and build national character, Lin notes that the budget allocated to promoting Taiwanese culture was significantly larger than the one for Chinese culture.

Chiang Kai-shek would surely turn in his mausoleum upon hearing that!

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of