With less than a year to go before the 2020 US census, advocates are encouraging Taiwanese respondents to write in “Taiwanese” on the form’s race question instead of just checking off the box for Chinese.

“There is strength and power in numbers, in being noticed by the government,” Christina Hu (胡若涵), a civic engagement director with the nonprofit Taiwanese American Citizens League, says.

Hu, who is helping spearhead the Write In Taiwanese Census 2020 Campaign, says they’ll be pulling out all the stops to convey to Taiwanese the importance of differentiating themselves from Chinese on the congressionally mandated headcount, done once every 10 years.

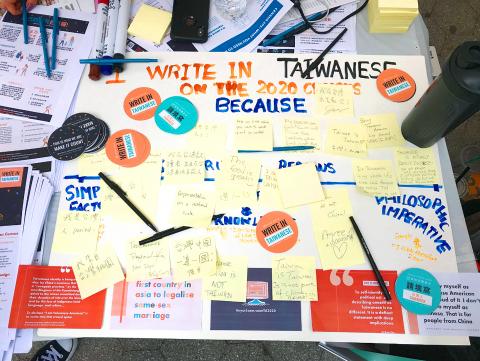

Photo courtesy of Christina Hu

The league plans to produce two public service announcements in October in English, Mandarin, Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) and Hakka, Hu says. She adds that they’ll be fundraising for those PSAs beginning this summer.

The group, which organized similar efforts in previous censuses, has also been deploying social media like Facebook and Instagram, using the handle @write.in.taiwanese.census to help spread the message.

“People who identify as Taiwanese [are] not often recognized, and a lot of times we have to defend ourselves,” Ben Ling (林君威), a past president of the Taiwanese American Citizens League, says. “So having this be legitimized where we are actually counted pretty much legitimizes our identity.”

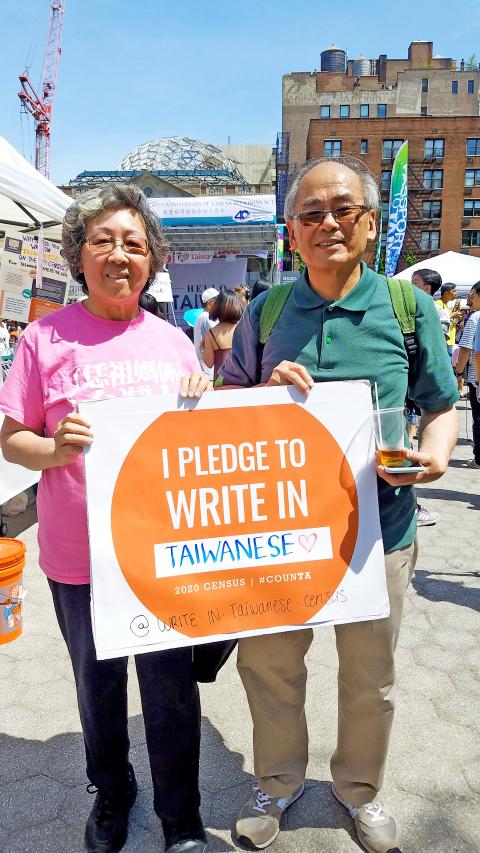

Photo courtesy of Christina Hu

A LOT AT STAKE

The census is used to determine how more than US$800 billion a year in federal funds is allocated, as well as to decide the number of seats awarded to states in the House of Representatives and the way representative boundaries are drawn.

Community advocates have been ramping up efforts to educate the public about the importance of filling out the questionnaire, which, unlike in previous counts, will be completed primarily online in 2020.

Photo courtesy of Christina Hu

But getting people to participate can be tough. A US Census Bureau survey released earlier this year found that Asian Americans were least likely to fill out the census form and were most concerned their answers would be used against them.

This comes amid growing mistrust about how data is used and a Trump administration push to include a citizenship question, which advocates worried would discourage participation in the census.

The US Supreme Court recently tossed the controversial question from 2020 census forms. Following that ruling, the Trump administration said it would omit the question.

Photo courtesy of Christina Hu

Meanwhile, some Chinese Americans, many of them immigrants, have decried government efforts to collect and publish detailed data on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, fearing it could be used to advance race-based policies.

Some have even reportedly advocated not answering the census race question, which is used to establish guidelines for federal affirmative action plans and monitor compliance with the Voting Rights Act, among other things.

Advocates worry such actions could generate inaccurate census results. That, in turn, could impact funding levels for programs like Medicaid and food stamps, not to mention grants and loans for state and local governments, companies and nonprofits.

Photo courtesy of Christina Hu

STAND UP AND BE COUNTED

For many Taiwanese, the census is an opportunity to stand up and be counted.

In 2000, the census recorded around 145,000 Taiwanese living in the US, accounting for just 1 percent of all Asians. That number rose to around 215,000 in the last census in 2010, roughly a 50 percent increase.

Yeh Chieh-ting (葉介庭), Ketagalan Media cofounder who is handling media relations for the Taiwanese write-in campaign, attributes the population jump to a similar outreach effort in 2010.

“We’re talking about people over this 10 year period who decided that it was worth their while to bother to check ‘other’ and to write in ‘Taiwanese’ and to spell it correctly,” Yeh says, adding that they’re trying to keep the momentum going for 2020.

Ling says he believes the Taiwanese community was still vastly undercounted in the last census, though a Census Bureau report in 2012 found that Asians in general were not.

The Census Bureau said information about the 2020 census will be mailed out to most addresses beginning next March. People will be able to respond online, by mail or by phone.

The race question allows respondents to mark one or more boxes and write in their origins. It features checkboxes for Chinese, Korean and Japanese, among others, but not for Taiwanese.

The Write In Taiwanese Census 2020 Campaign urges people filling out the census to write in “Taiwanese” if they or their family came from Taiwan, or if they can trace some of their heritage to the country.

Apart from the question of identity, advocates point out that being specific about subgroup on the race question helps expose differences and disparities within the vastly diverse Asian American community.

That nearly four in five Taiwanese in the US have a bachelor’s degree or higher, or that 4 percent of Taiwanese have no health coverage, are statistics that otherwise would get lost if respondents did not write in Taiwanese.

But that data, advocates caution, is accurate only when all Taiwanese living in the US complete the questionnaire — and indicate that, in fact, they are Taiwanese.

“Writing in Taiwanese is important because the community of Taiwanese Americans does exist, with all its heritages and narratives about who we are,” Yeh ays. “So we’d like that to be reflected as accurately as possible in the official government data of the United States.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she