May 13 to May 19

After browsing over Wang Da-hong’s (王大閎) plans for Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) nodded, smiled and even offered a few words of approval.

“He was polite; he knew my personality,” the China-born, Europe and US-educated Wang recalled, referring to a 1961 incident where his insistence on his ideals cost him the chance to design the National Palace Museum (NPM).

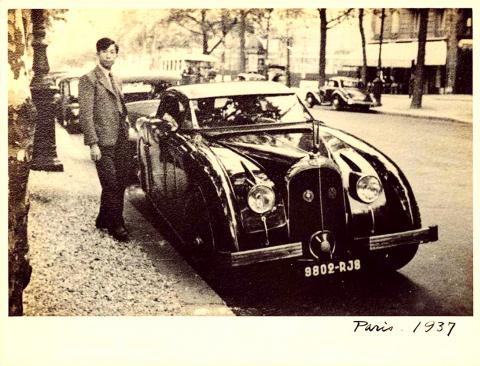

Photo courtesy of Hsu Sung-ming

A few days later, Wang received a call from Chiang’s secretary — the president thought the building was too Westernized; it needed to be more Chinese. The submission guidelines specifically asked for a building that would reflect Chinese culture while drawing from Western elements, but having lived in Europe and the US from the age of 13 to 28, Wang’s thinking was probably too progressive for the conservative government bigwigs.

It was late 1965, and China was on the eve of the Cultural Revolution, which would soon smash many things traditional. Chiang’s government in Taiwan was still clinging to its spot in the UN as the legitimate ruler of China, and it would benefit Taiwan to portray itself as the rightful heirs of Chinese culture. The NPM was completed earlier that year, and Sun’s memorial was Chiang’s next pet project.

Wang was unhappy with the request, but after the NPM debacle, he had learned to compromise. It took almost two years for Chiang to approve what Wang considered his “most difficult project ever,” breaking ground on March 12, 1968 and opening on May 16, 1972.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FIFTEEN YEARS IN THE WEST

Wang was born in Beijing to a prominent family as the son of Wang Chung-hui (王寵惠), a close associate of Sun who joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in 1912 and held a number of important positions during its time in China. After the KMT fled to Taiwan, the elder Wang served as minister of justice until his death in 1958.

Through his father’s work in Europe as a diplomat, the younger Wang enrolled in a Swiss academy as a teenager, later completing his master’s degree in architecture at Harvard University, where he studied alongside I.M. Pei (貝聿銘) under Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius. He returned to China in 1945 and set up shop, moving to Taiwan via Hong Kong in 1952.

Photo: Liu Te-hsin, Taipei Times

Wang’s first attempt at public architecture was the proposal submitted for the NPM in 1961. While the authorities chose his design, Wang’s ideas were too progressive for the committee, leading them to hand the project to one of the jurors. According to an article on Wang by architecture professor Hsu Ming-sung (徐明松), Wang commented: “Politicians should be politicians, and professionals should be professionals.”

Wang died in May last year, leaving behind an architectural legacy in Taipei. He was responsible for a number of buildings on the National Taiwan University campus, the Lin Yutang House (林語堂故居) at Yangmingshan, numerous structures at Academia Sinica, the Asia Cement building as well as the current Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Education.

His private residence on Taipei’s Jianguo S Road (建國南路) was his first project in Taiwan, representative of his combination of classical Chinese design elements with modern techniques. Demolished in the 1970s, it was rebuilt in 2017 at Fine Arts Park as the Wang Da-hong House Theater.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

IMMORTALIZING SUN

Chiang first brought up the idea for a memorial hall for KMT founder Sun Yat-sen during a Central Standing Committee meeting in 1963, calling for a task force to prepare for Sun’s upcoming 100th birthday on Nov. 12, 1965. One of its five directives was “construction of a memorial hall.”

“In addition to grand ceremonies during [Sun’s] 100th birthday, we especially need a hardware facility that inherits the past and inspires the future in order to show our eternal remembrance of [Sun],” Chiang said.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Wang answered the call for design submissions, beating out 11 other architects for the prize. According to an oral history published by the memorial, Chiang was not the only one who thought the design was too Western. Committee members expected a imperial Chinese design like the Grand Hotel (圓山飯店), and could not understand why Wang incorporated so many modern elements into his proposal.

A poor speaker, Wang had to explain to each official that since Sun fought against imperial rule, it would be an insult to him for his memorial to completely imitate Qing-era architecture, which he described as “extravagant and decadent.” This decadence, he argued, was exactly what led Sun to start a revolution.

EVOLVING SPACE

When the memorial was first complete, then-Taipei mayor Henry Kao (高玉樹) proposed that no civilian building nearby should be taller than the memorial. Again, Wang argued that such restrictions would clash with Sun’s democratic ideals. Kao agreed — otherwise that area of Taipei would have looked quite different today.

Kao explains in the same oral history that the land the memorial occupies was originally designated for “Park No. 6.” He ordered the demolition of illegal structures in the vicinity as well as the removal of military rail tracks for a nearby armory, while the remaining land mostly contained rural paths and rice paddies. A large amount of dirt was needed to create level ground to build the memorial, and the hole dug in a corner of the grounds became today’s Lake Cui (翠湖).

Chiou Chi-yuan (邱啟瑗) writes in The Reformation and Development of National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in Taiwan (台灣國父季輾館之變革與發展) that the hall focused on highlighting Sun’s accomplishments as well as the KMT’s achievements compared to the condition of China. Until 2002, the displays were curated by a team from the KMT Party History Institute (黨史館) who set up office on the memorial grounds. Today it is administered by the Ministry of Culture.

Chiang’s funeral in 1975 was held here, and his son Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) and his successor Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) both assumed their presidencies at the memorial hall. While there is still rich material about Sun’s life, the hall is now better known for hosting various exhibitions and performances, including the Golden Horse and Golden Bell Awards.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,