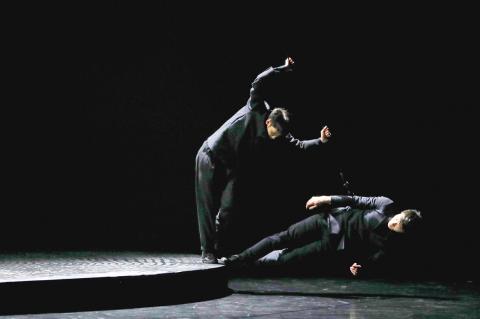

Fans of Taiwanese choreographer Huang Yi (黃翊) have been waiting years to see his work take the main stage at the National Theater, but the wait proved worth it as his new production, A Million Miles Away (長路), opened the 11th Taiwan International Festival of Arts (TIFA) on Feb. 16.

A dark, stark, minimalist exploration of time and memory that is as emotionally reserved and quiet as its creator, A Million Miles Away is heartbreakingly beautiful and a major achievement for Huang Yi, his dancers and his production team, even if it could do with some judicious trimming of the opening and finale.

A powerful follow-up to Huang’s Under The Horizon (地平面以下), staged in October last year at Taipei’s Metropolitan Hall as part of the Taipei Arts Festival, A Million Miles Away has none of the technological razzle-dazzle that Japanese audiovisual artist Ryoichi Kurokawa gave to that piece or Huang’s own innovations in his Spin series or Symphony Project (交響樂計畫之) works of a decade ago.

Photo: CNA

But that simplicity is at the heart of its appeal. Not only is the color palette monochromatic, Huang uses just one piece of music, French composer Maurice Ravel’s Pavane pour une infante defunte, although in several versions.

A Million Miles Away is set upon a massive 9m diameter turntable, that, like time grinds ever onward, sometimes slowly and sometimes as fast as a merry-go-round. There is just one brief slip backwards.

The dancers, who begin by stripping down completely and then reassembling themselves, emerge and disappear from the dark void that is most of the stage. They stumble and totter, struggle to maintain connections or fight against lines that link them together, at the mercy of the wheel’s centrifugal force.

Metaphors are writ large — life is a balancing act, sometimes people live right on the edge, the ties that bind are hard to escape, childhood pains are difficult to forget. Sometimes the images resemble Jimmy Liao (幾米) illustrations, if he drew just in black, grey and white.

Black balloons appear toward the end, planets tethered in the air as a father loses his grip on his young son. A red balloon is the first bright color to appear in the entire show, but it is lost and floats away.

I won’t give away the ending, but Huang finishes on an upbeat note, with blades of grass emerging from the wood whirls on the wheel.

Huang said the show grew out of Floating Domain, which he created for Cloud Gate 2 (雲門2) in 2010 and then expanded in 2014, a piece that I found dark and depressing. A Million Miles Away, in contrast, is dark, but only in terms of the lighting.

Chen Wei-an (陳韋安), Chung Shun-wen (鍾順文), Li Yuan-hao (李原豪) were added to Huang’s long-time collaborators Hu Chien (胡鑑), Lin Jou-wen (林柔雯) and Luo Sih-wei (駱思維), and the choreographer appears at the end for a touching segment with Hu.

The turntable, which was designed by Chen Wei-han (陳暐涵), looks massive, but was made for travel — it is aluminum and divides into slices like a pizza so that it can be assembled easily. It is a bit noisy, which some might find distracting; I thought it gave an urban soundscape to the production.

A Million Miles Away will be performed at the National Taichung Theater on May 18 and 19, and the National Kaohsiung Center for the Arts (Weiwuying) on May 25 and 26.

If you missed the shows in Taipei, which were close to sold out, a trip south would be well worth it. Huang, just in his mid-30s, is one of the major voices of his generation, and A Million Miles Away should not be missed when it is still at home.

‘TOSCA’

The National Symphony Orchestra’s (NSO, 國家交響樂團) concert version of Tosca at the National Concert Hall on Saturday night was a reminder of what I love and hate about Western opera: lush, soaring and soul-moving music, but awkward, often wooden acting and movement.

Far more so than theater and dance, opera requires its viewers to ignore physical reality, yet seeing an opera with singers who have not only the vocal and acting chops is possible.

The NSO billed this concert version of Tosca as a “pure musical experience,” meaning, I guess, that it wanted audiences to focus on the music and not be distracted by elaborate sets or costumes.

That is all well and good, but the cast still has to do some acting, and I found myself wishing that Cloud Gate Dance Theatre (雲門舞集) founder Lin Hwai-min (林懷民), who directed the production, had been able to include some movement classes for the leads so they were not so stiff.

Lin had the unenviable task of having to find room for not only the orchestra, wonderfully conducted by Lu Shao-chia (呂紹嘉), on the concert hall’s stage, but for more than 70 members of the Taipei Philharmonic Chorus (台北愛樂合唱團) and the Taipei Philharmonic Children’s Chorus (台北愛樂兒童合唱團) for the Te Deum at the end of Act I.

It was a tight squeeze, but he managed it by having the chorus members portraying townspeople enter the hall through the auditorium doors and climb up two sets of side steps to the stage, while the church processional came down the hall’s right-hand aisle and then onto the stage.

He also used the narrow walkway in front of the hall’s massive pipe organ as a second platform, standing in for the parapets of the Castel Sant’Angelo, to great effect.

Saturday night’s cast was almost all Taiwanese: Lin Ling-hui (林玲慧) as Tosca, Ezio Kong (孔孝誠) as Cavaradossi, Julian Lo (羅俊穎) doubling as Angelotti and the jailer, Tang Fa-kai (湯發凱) as Spoletta and Chao Fang-hao (湯發凱) as the sacristan and Sciarrone. The sharkskin suit-clad Singaporean baritone Martin Ng (吳翰衛) was the exception.

Lin Ling-hui’s voice was in fine form and her performance of Vissi d’arte in Act II was really lovely, as was Kong in E lucevan le stele in Act III.

Ng is a solid singer, but not quite lecherous or malevolent enough in the role of Scarpia. I found myself wishing NSO would do more operas with a major role for a bass; I love Lo’s voice and he was more than able to hold his own in Act I against the orchestra and Kong, whereas Chao was sometimes overshadowed.

The same cast will perform when the NSO takes Tosca to the Pingtung Performing Arts Center on March 8 and the Jhongli Arts Center in Taoyuan on March 15.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern