Jan. 14 to Jan. 20

After World War II, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) started hunting down hanjian (漢奸, traitors to Han Chinese). But a tricky situation arose when 96 out of 195 suspected hanjian tried in Xiamen were actually Taiwanese.

According to the Hanjian Punishment Act (懲治漢奸條例) then in force, a hanjian was “a Chinese who directly or indirectly collaborates with the enemy, using various methods to hinder our military, sabotage our strategy, leak our secrets and harm our compatriots.”

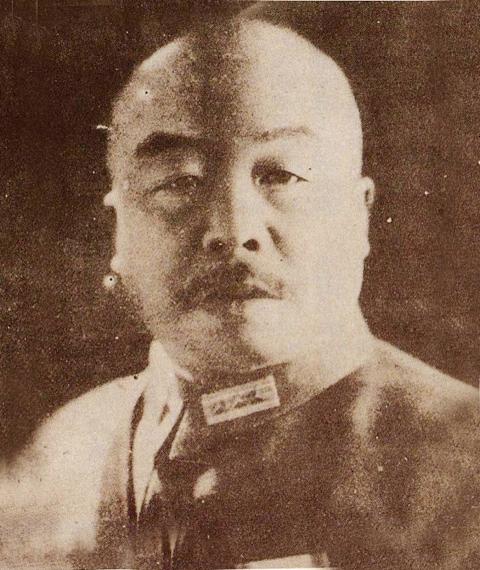

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A July 1947 government report showed that 26,970 people had been charged as hanjian, with 342 executed and 847 sentenced to life in prison. However, the authorities weren’t quite sure what to do with those Taiwanese who had been Japanese citizens up until 1945. The KMT saw them as a “deeply poisoned populace” brainwashed by the Japanese, and many had indeed worked closely with the colonial government or taken part in the Japanese war effort in China.

Quite a few Taiwanese were working in Japanese-occupied areas of China such as Xiamen. Historian Chen Tsui-lien (陳翠蓮) writes in Historical Rectification in Postwar Taiwan (台灣戰後初期的歷史清算) that while the bulk of them were civilians making an honest living, there were also those who turned to shady activities and were in cahoots with Japanese secret agents.

Even though the Judicial Yuan in January 1946 clarified that Taiwanese could not be tried as hanjian, they were still included in anti-hanjian purges across China. And in Taiwan, the governor-general Chen Yi (陳儀) also ignored the interpretation and asked people to report suspects between Jan. 16 and Jan. 29, 1946, collecting 335 names and arresting 41 over the next few months.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Digital Archives

The Taiwan Minpao (台灣民報) newspaper protested, writing: “As Japanese citizens, Taiwanese bore the same responsibilities as Japanese, including fighting alongside them in the Japanese Army. According to the government’s definition, then, all Taiwanese can be seen as hanjian. Every single person who lived in Taiwan before Japanese surrender has helped the enemy in some way.”

WHO’S A ‘HANJIAN’?

After World War II, there was much Chinese resentment toward Taiwanese living in China. In September 1945, Guangzhou’s governor ran an article in the local newspaper in response to attacks on the 8,000-strong Taiwanese community.

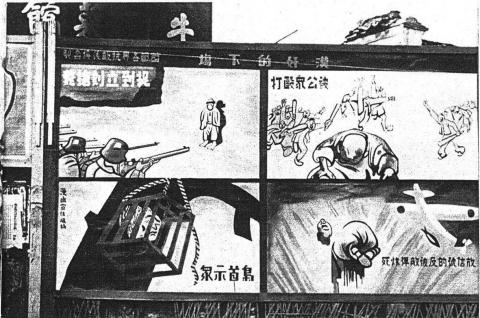

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“The Taiwanese have been deeply poisoned by the Japanese in the past, but they have realized their mistakes. We should act generously and help re-educate them so they can rediscover their conscience,” the article read.

Incidentally, the first war criminal executed in Guangzhou on Nov. 25, 1945, was Hsinchu native Chen Chin-tien (陳錦添), a minor officer charged with murder and selling opium on behalf of the Japanese government. The press closely followed his case, stressing that he was brainwashed by the colonizers, had “no recognition of the motherland” and even commenting that the execution was very “satisfying to watch.”

Despite the efforts of KMT figures, especially Taiwan-born and China-raised Chiu Nien-tai (丘念台), to protect Taiwanese, 74 were arrested in Guangdong’s anti-hanjian purges between November 1945 and May 1946.

However, even the Bureau of Investigation and Statistics wasn’t sure whether Taiwanese could be considered hanjian.

“We have found that hanjian should be limited to citizens of [the Republic of China]. Taiwan has fallen to Japan for 50 years, and it was the Qing Empire who ceded it. Therefore, Taiwanese were not citizens of our country until we reclaimed Taiwan. Those Taiwanese who participated in the killing, looting and burning alongside the Japanese troops should be tried under the appropriate war crimes, and it seems that those who were forced to join the Japanese Army or worked for the Japanese occupiers across China should not qualify as hanjian.”

The Bureau asked the Judicial Yuan for an interpretation. The Judicial Yuan concurred, confirming that as Japanese citizens during the war, Taiwanese should fall under international law instead of the hanjian provisions.

However, the regional courts continued to challenge the interpretation. In July 1946, the Shanghai High Court quoted KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) orders in its argument:

“During the struggle against the Japanese, any Taiwanese who commit illegal acts and collude with the enemy to harm our people should be treated as hanjian without leniency.”

Before the purges in Taiwan, the KMT’s anti-hanjian laws were printed in the local newspapers with a note that these rules fully applied to Taiwanese.

The state-run Taiwan Hsin-sheng Pao (台灣新生報) newspaper originally maintained that Taiwanese could not be considered hanjian, but after the Taiwan Garrison Command announced the purges, it quickly changed its rhetoric, stating that there “are many shameless people who worked for the enemy to oppress the Taiwanese… they should not be shown leniency.”

Due to the broad definition of hanjian, there was some unrest as people weren’t sure who to report. The newspaper tried to clarify in an editorial, noting that although it’s hard to define a Taiwanese as hanjian, the “following three types of hanjian are indisputable: those who seek independence, those who oppose the government and try to cause social unrest and those who collude with Japanese after the war to loot national property.”

“As an official publication, the Taiwan Hsin-sheng Pao made several corrections and changed its stance on hanjian policy. This shows that even the government was unsure of how they felt toward Taiwanese hanjian,” Chen Tsui-lien writes.

CHEN YI’S WITCH HUNT

Forty-one people were arrested on governor-general Chen Yi’s orders, including prominent figures such as Ku Chen-fu (辜振甫), Lin Hsiung-hsiang (林熊祥) and Hsu Ping (許丙), who were accused of plotting independence. Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) avoided this fate through his connections.

Critics found it hypocritical that the KMT decided not to seek war reparations from Japan but punished the Taiwanese instead.

However, the witch hunt did not stop. In August 1946, Chen Yi denied public rights to those who held important positions in the Komin Hokokai political organization and those reported as being hanjian — continuing to ignore the Judicial Yuan’s interpretation. This law was widely criticized as it took effect before the person was proven guilty.

In a period of national mobilization for the war effort, numerous Taiwanese were essentially compelled to join the Komin Hokokai, which contained numerous umbrella organizations that included youth groups as well as medical and artist brigades.

Despite repeated warnings from the central government, Chen Yi refused to stop, carrying on until the outbreak of the anti-government uprising and crackdown now known as the 228 Incident.

“Chen’s government was convinced that Taiwanese were unhappy with the KMT due to the ‘slave mentality’ instilled by the Japanese and their lack of identification toward the motherland. Therefore he insisted on continuing the purges to weed out any potential dissidents,” Chen Tsui-lian writes.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Dec. 22 to Dec. 28 About 200 years ago, a Taoist statue drifted down the Guizikeng River (貴子坑) and was retrieved by a resident of the Indigenous settlement of Kipatauw. Decades later, in the late 1800s, it’s said that a descendant of the original caretaker suddenly entered into a trance and identified the statue as a Wangye (Royal Lord) deity surnamed Chi (池府王爺). Lord Chi is widely revered across Taiwan for his healing powers, and following this revelation, some members of the Pan (潘) family began worshipping the deity. The century that followed was marked by repeated forced displacement and marginalization of

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and