Dec.10 to Dec.16

After several setbacks — including falling off a donkey and injuring his arm — Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) finally set out from Keelung on May 15, 1927 with his second son in tow. With his oldest son studying in London, Lin felt that this was the best time to fulfill his longtime dream of visiting Europe and the US.

Lin, a prominent political activist under Japanese colonial rule, was urged by his comrades not to take the trip. It was a crucial moment for Taiwan’s autonomy movement, as Lin’s faction had just quit the leftist-dominated Taiwanese Cultural Association (臺灣文化協會) in January, and was planning to form Taiwan’s first political party.

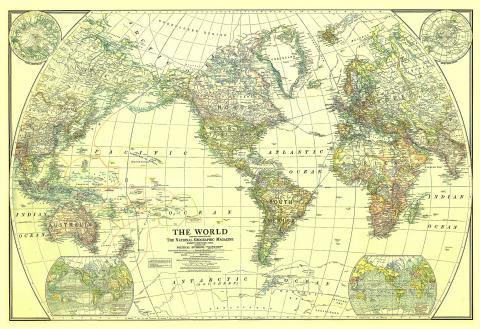

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lin writes in his diary that it was now or never for his journey, departing just two weeks before his associate and revered democracy pioneer Chiang Wei-shui (蔣渭水) founded what would become the Taiwanese People’s Party (台灣民眾黨).

Lin spent 378 days visiting more than 16 countries and 60 cities. His detailed travel accounts first appeared in the Chinese-language newspaper Taiwan Minpao (台灣民報) in August 1927, and ran until October 1931. Lin attempted to turn the material into a book, but died midway through the editing, leaving his secretary Yeh Jung-chung (葉榮鐘) to finish compiling Lin Hsien-tang’s Travel Writings from around the Globe (林獻堂環球遊記).

EMULATING THE WEST

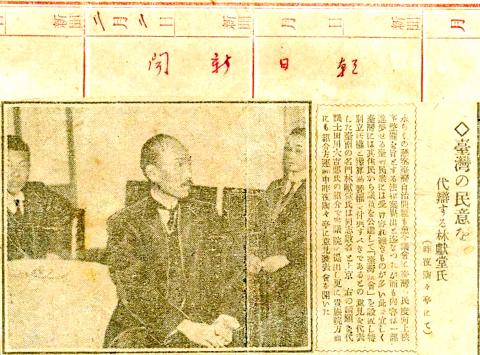

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Lin was heavily influenced by the travel accounts of Qing Dynasty scholar and reformist Liang Qichao (梁啟超), who fled China after his failed efforts to modernize the nation. When the two met in Japan in 1907, Lin asked Liang for his opinion on the future of Taiwan.

Liang suggested that Lin emulate the Irish struggle against British rule. This idea of taking inspiration from other countries’ experiences undoubtedly fueled Lin’s desire to see the West for himself.

Liang visited Taiwan in 1911 and further advised Lin to expand his horizons beyond literature, to closely study politics, economics and social thought.

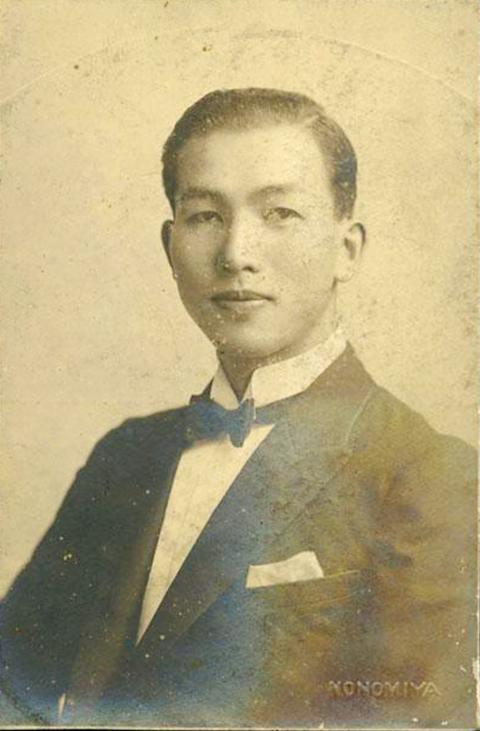

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lin was one of the few Taiwanese who had the money and status to travel to the West, but he was not the first to write about his experiences.

Huang Chao-chin (黃朝琴), who would become Taipei’s first mayor under Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule, studied at the University of Illinois in 1923 and also published an account of his travels in Taiwan Minpao.

Yan Kuo-nien (顏國年), a wealthy businessman from New Taipei City’s Rueifang District (瑞芳), set out from Keelung in 1925 but took the opposite route from Lin, heading east to the US first, circumnavigating the globe in about 220 days.

Photo courtesy of digitalarchives.tw

According to the book The Traveler’s State of Mind (旅人心境) by Lin Shu-hui (林淑慧), Yan’s account largely contains matter-of-fact observations of the economic, industrial and material development of the countries he visited. In contrast, Lin’s humorous and introspective prose focuses on values such as freedom and equality. This makes sense when considering their goals — Yan wanted to expand his coal-mining empire, while Lin had dedicated his life to the struggle for Taiwanese consciousness and autonomy.

“Lin’s prose reflected his deep feelings toward living under colonial rule,” Lin Shu-hui writes.

However, Yan’s book was meant for family and friends and was not widely publicized, whereas Lin’s book had “considerable influence” on Taiwan’s social and political movements, writes historian Hsu Hsueh-chi (許雪姬) in her introduction to the 2015 edition of Lin’s book.

“Lin was not a typical tourist… He hoped to learn about the strengths of Europe and the US to help Taiwan,” Hsu writes.

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL COMMENTARY

Lin’s first stop was Xiamen, followed by Hong Kong, Malaysia and Sri Lanka. He reached Europe on June 17, 1927, after riding camels and touring the pyramids in Egypt. He spent considerable time in London and Paris, using the latter as a base from which he explored the surrounding countries. It was from Paris that Lin set out on March 14, 1928, reaching New York in a week. After crossing the continental US, he returned to Asia via San Francisco. Although long-distance travel was mostly done by train and ship in those days, Lin jumped at the chance to take a plane for the first time in Los Angeles.

It’s impossible to cover all of Lin’s detailed and thoughtful observations. Probably the most interesting part is the social commentary that he provides, which closely mirrored his ideals as a political activist.

One notable passage is the one on the status of women in the US, which Lin thought was the highest in the world: “When a man meets another man in the street, they just nod to each other; whereas they will take off their hat when encountering a woman… If a woman enters a packed streetcar, the men will stand up and let her sit. It’s not just like this with the upper class, but throughout society. This is why there’s the saying, ‘To measure how civilized a country is, one just needs to look at how their women are treated.’”

Lin also muses on the prevalence of lynching black people in the US, writing: “It’s hard to believe that such inhumane practices are still taking place in plain sight in the 20th century.”

In the UK, he visited the execution site of Charles I, commenting: “He went against the will of the people and insisted on authoritarianism, and ended up losing his head. I wonder how many people in power around the world are still making the same mistake as Charles I? It’s so hard to comprehend!”

Lin does not make explicit his envy toward the intense debates at Speakers’ Corner in London’s Hyde Park, but it’s apparent in his prose: “After each speech, the crowd of thousands roar in applause. Four or five policemen can be seen, but they do not interfere. What freedom of speech they enjoy!”

Lin’s musings after visiting Monaco perhaps encapsulate his feelings as part of a colonized people: “Even though Monaco has little land, people and production, it’s ruled competently. This shows that there is no territory and no people in the world that cannot be independent. The only thing that matters is the people’s ability to govern themselves. If they can’t, then even a country as large and bountiful as India will be reduced to a colony.”

The book is truly a fascinating read and paints a picture of Lin that may be hard to glean from other historical materials. Unfortunately, it’s not available in English.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she