Nov. 19 to Nov. 25

In 1931, the Japanese colonizers forbade the Sediq Aborigines from holding their annual seeding festival — presumably due to a violent rebellion and punitive campaign a year earlier, which came to be known as the Wushe Incident (霧社事件). The festivities would not be revived until 2011.

These “revivals” have been consistently taking place across Taiwan in recent years — in 2014, the Rukai village of Teldreka revived its rain praying festival after 35 years. According to village elders, the ceremony could not be performed too often as too much rain would cause the rivers to flood — and eventually they were unable to find anyone with the knowledge or willingness to perform the ceremony.

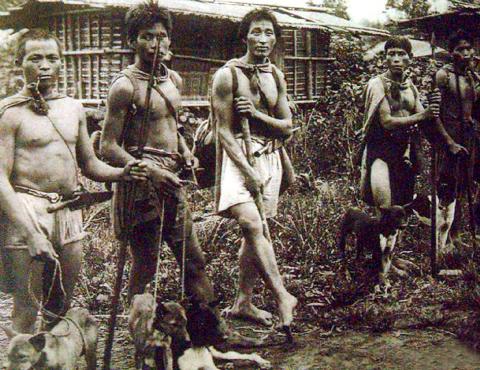

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Due to the relentless assault on traditional culture by outside forces — whether it be missionaries, unfriendly government policies, assimilation to Han Chinese culture, population shift or modernization — countless Aboriginal festivals have disappeared and reappeared over time. While the revived festivals often take on an additional tourism element, they still serve as a source of pride and identity for Aborigines who are reclaiming their endangered cultures.

One festival that has endured through the centuries, however, is the Pasta’ay, or Ritual of the Short Black People (矮靈祭). It is held by the Saisiyat, one of the smallest Aboriginal communities in Taiwan who live in both Miaoli and Hsinchu counties. The festival, which is held every two years to appease the spirits of a neighboring tribe of ta’ay, or “short black people” whom the Saisiyat killed off centuries ago, began yesterday and will continue through tomorrow night.

COLONIAL CHANGES

Photo courtesy of Kaohsiung Water Resources Bureau

Aborigines along the fertile western plains assimilated with Han Chinese during the latter’s mass migration throughout the 1700s and 1800s, and while the Qing Empire initially tried to separate the two peoples, it gave up in the 1880s because it realized that it could not stop the tide of Han Chinese expansion.

With the lowland Aborigines largely assimilated and “pacified,” the Japanese colonial authorities turned their sights toward the hostile ones in the mountain areas, building roads, setting up police governors and promoting Japanese education.

Elders of the Kavalan people recall that the Japanese confiscated the people’s firearms in 1910 and outright banned their qataban, or headhunting festival, telling them that such practices were uncivilized superstition and encouraged them to take up Shintoism. The young village leaders were also recruited to work for the government, often leaving their traditional areas for various tasks, contributing to the demise of traditional culture.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Japanese also brought societal changes as they encouraged the nearby Amis people to farm, leading to increased intermarriage and cooperation between the two peoples.

“The Amis are often working in our rice paddies now, it just isn’t right to sing songs about taking their heads anymore,” a Kavalan elder says in Liu Pi-chen’s (劉璧榛) in a study on qataban while explaining why they have no desire to revive qataban.

Furthermore, under government policy, Aborigines made less money than Han Chinese performing the same job, leading many to abandon their identity altogether.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Puyuma politician and educator Paelabang Danapan writes in Ethnic Structures through the Cracks (夾縫中的族群建構), “Aborigines during the Japanese era, especially educated elites, carried strong anti-traditional ideas of ‘progress.’ When these people deny the value of headhunting, shamanism and other practices, they essentially unconditionally surrender their cultural subjectivity.”

“This was not a natural [loss of tradition] of a hunter-gatherer tribal society moving toward an agricultural nation,” Liu writes. “It was an unnatural destruction caused by colonialism.”

ASSIMILATION FOR EQUALITY?

After World War II, Liu writes that the Christian missionaries brought further changes by successfully converting many Aboriginal communities. Meanwhile, the government’s assimilation policies continued under the guise of “improving our mountain compatriots’ lives and eradicating their backward customs.”

“Under high pressure to assimilate to Chinese culture and to escape the stigma of being a ‘savage,’ the Kavalan people chose to strive for the recognition of the higher-status Han Chinese people, and also started identifying as Amis due to increased intermarriage. In this type of environment, nobody would even think of, or dare, revive qataban,” Liu writes.

Paelabang Danapan writes that these policies were carried out under the constitutional guarantee of equal rights to all ethnic groups — but “this ‘equality’ was simply a one-sided construction by the government machine, which completely ignored the feelings and desires of the Aborigines.”

This colonial mentality persisted until recent decades. As late as 1994, Saisiyat History: Pasta’ay (賽夏史話:矮靈祭), states that under government assistance, Aborigines now “use chopsticks instead of their hands, eat nutritious food, wash their faces, cut their hair, take showers and know how to use and save money.”

With the beginning of the Aboriginal rights movement in the 1980s, which continues through today, it was only a matter of time before they would start to reclaim their traditions.

ENDURING FAITH

Throughout all these historical changes and loss of tradition and culture, the Pasta’ay ceremony never disappeared.

The ceremony’s tenacity is likely due to the significance the ritual has toward the Saisiyat, who, according to legend, were cursed by the Ta’ay to die out unless they faithfully and regularly performed the ceremony.

“The Saisiyat has been able to pass on this ceremony for 400 or 500 years purely through devotion to their beliefs,” Chen Ying-chen (陳瑩真) writes in a 1995 study on Pasta’ay. “There are no written records or material and it’s all passed on orally.”

Ethnomusicologist Hsu Chang-hui (許常惠), who is noted for his exhaustive survey of Taiwan’s traditional folk music from 1966 to 1978, visited the Saisiyat in 1985 to study the Pasta’ay. He noted that even though most people under 50 could not understand the songs they were singing, “all the elders [he] spoke to strongly believed that the Pasta’ay had to be passed on at all costs.”

“If we don’t worship the Ta’ay, we Saisiyat will be punished,” an elder told Hsu. “The Ta’ay taught us how to survive in these parts, and without the Pasta’ay, there won’t be Saisiyat. So no matter what, we have to continue this tradition.”

Another elder makes the exact same statement in Chen’s study: without Pasta’ay, there won’t be Saisiyat. Modernization, assimilation and the attention of outsiders toward the ceremony for tourism purposes continue to threaten the Pasta’ay, but for now, the Saisiyat still hang on to their centuries-old faith.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the