Cloud Gate Dance Theatre (雲門舞集) artistic director Lin Hwai-min (林懷民) is still more than a year away from retirement, but the company and its fan base have already begun the long goodbye to a man who took his dream of a small company and produced not only a world-renowned troupe and major ambassador for the nation, but along the way helped propel Taiwan into a powerhouse of contemporary dance.

Lin forged a new path for dancers in the Chinese-speaking world by establishing the first professional company in Taiwan. The company is now celebrating its 45th anniversary, and its annual fall tour of the nation is a special gala program of highlights of the past 20 years of Lin’s works.

No one could be more surprised about reaching such a milestone than Lin himself, as he said in a telephone interview earlier this month.

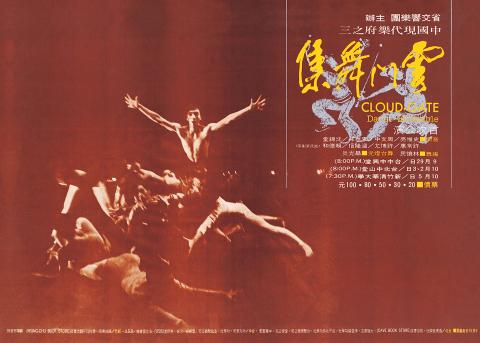

Photo courtesy of Liu Chen-Hsiang

He was already a published author before entering National Chengchi University to study journalism. He left Taiwan in 1969 to study at the University of Missouri, but switched to the University of Iowa after winning a fellowship to its International Writing Program.

While he had taken some dance classes growing up, despite his father’s disapproval, it was not until age 23, while in the US, that he had the opportunity and the time to take classes regularly.

When he returned to Taiwan, he wanted to continue to dance, so he gathered a group of like-minded people, even though none of them had professional experience.

Photo courtesy of Barry Lam

Lin has said he never intended to become a choreographer; the idea was that the group would eventually be able to hire choreographers to create works for them, but in the meantime, he would try his hand. He had to teach himself how to choreograph.

However, one thing Lin and his first dancers agree on was that they wanted works that reflected their own culture, not just imitate Western modern dance. The inspiration for many Lin’s early works came from classical Chinese literature — such as The Dream of the Red Chamber (紅樓夢) — folktales and traditional theater.

The troupe’s relationship with Taiwan was cemented just five years later, in 1978, with Legacy (薪傳), the first performance of which came just as the US broke relations with Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Cloud Gate Dance Theatre

The attachment, the feeling of ownership that Taiwanese have for Cloud Gate, its dancers and Lin, is probably unique in the world. Many countries have national troupes, but they have not been taken to heart in quite the same way.

Lin said people are always telling him about the first time they saw the company, stopping him on the street or at the theater or when he is shopping.

“When I bought the trees for the theater [in Tamsui], we saw two people jumping around back in the trees. The couple came up to talk and the wife said her husband would always buy expensive tickets to see Cloud Gate when they were dating, but after they were married he didn’t and they stopped going,” he said. “Grannies tell me about taking their grandchildren to see the company.”

Photo courtesy of Liu Chen-Hsiang

For the 45th anniversary gala program, Lin said he picked the pieces that his dancers were most comfortable with, and ones that would showcase his senior dancers, six of whom are retiring at the end of this year.

Some have been in the company for 25 years, such as Chou Chang-ning (周章佞) and Yang I-chun (楊儀君), while Tsai Ming-yuan (蔡銘元) has 19 years, Huang Pei-hua (黃珮華) and Su I-ping (蘇依屏) have 17 each and Ko Wan-chun (柯宛均) has 14.

They are the third and fourth generations of Cloud Gate dancers and they anchored the company in the early 1990s, Lin said.

“They all still love dancing, but they are tired of touring,” he said.

He said there also pieces that he wanted to put in the show, but could not, such as the end of Legacy, because the dancers have to paint their bodies black for that part, which means they could not do another piece afterwards.

“It would be nice to do the really ancient works, but hard to find the time to rehearse them. We would have had to stop everything else … we just don’t have the time,” he said, referring to the company’s busy touring schedule over the past year.

As for the line-up, “who goes first, when they go out, also depended on what else they are doing, as well as the set and costume changes,” he said.

The program will open with Chou’s solo on the character for eternal (永) from 2001’s Cursive (行草) and ends with the finale of Pine Smoke (松煙) from 2003.

In between there are a mix of solos, duets and group pieces from 2001’s Bamboo Dream (竹夢), 1997’s Portrait of the Families (家族合唱), 1998’s Moon Water (水月), 2014’s White Water (白水), 2011’s How Can I Live On Without You (如果沒有你), 2013’s Rice (稻禾) and 2006’s Wind Shadow (風.影).

The selection not only highlights the virtuosity of the dancers, but shows the variety techniques that Lin developed over the years.

“All my works are simple,” Lin said.

Many people would beg to differ.

Cloud Gate is opening its national tour at the National Theater in Taipei tomorrow night, the first of nine performances, before traveling to Taichung, Kaohsiung and Tainan.

Tickets sold fast as soon as the tour was announced this summer and there are only a few seats left.

As part of the 45th anniversary celebrations, an exhibition of the company’s posters for performances in Taiwan and overseas tours opened earlier this month at the Cloud Gate Theater in New Taipei City’s Tamsui District (淡水) and runs through Dec. 30.

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

Article 2 of the Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China (中華民國憲法增修條文) stipulates that upon a vote of no confidence in the premier, the president can dissolve the legislature within 10 days. If the legislature is dissolved, a new legislative election must be held within 60 days, and the legislators’ terms will then be reckoned from that election. Two weeks ago Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (蔣萬安) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) proposed that the legislature hold a vote of no confidence in the premier and dare the president to dissolve the legislature. The legislature is currently controlled

Dull functional structures dominate Taiwan’s cityscapes. But that’s slowly changing, thanks to talented architects and patrons with deep pockets. Since the start of the 21st century, the country has gained several alluring landmark buildings, including the two described below. NUNG CHAN MONASTERY Dharma Drum Mountain (法鼓山, DDM) is one of Taiwan’s most prominent religious organizations. Under the leadership of Buddhist Master Sheng Yen (聖嚴), who died in 2009, it developed into an international Buddhist foundation active in the spiritual, cultural and educational spheres. Since 2005, DDM’s principal base has been its sprawling hillside complex in New Taipei City’s Jinshan District (金山). But