Oct. 15 to Oct. 21

During a village meeting in June, the residents of Ita Thao unanimously voted “yes” to remove all traces of the government-imposed name Dehua (德化) from the area. They had successfully renamed the village in 2000, but colonial vestiges still remained.

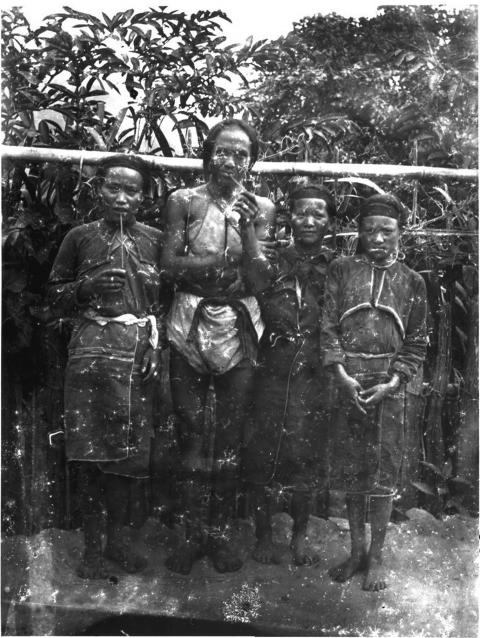

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“In colonial and authoritarian times, we were forced to use this discriminatory and stigmatized name,” Nantou County Councilor and village resident Rungquan Lkatafatu tells Taiwan Indigenous TV in a report. The villagers crossed off one item on their wish list on Wednesday last week, as the local Dehua police station was renamed Ita Thao. Their next target is Dehua Elementary School.

Occupying valuable land around Sun Moon Lake, the village’s Aboriginal Thao residents have suffered much since the arrival of outsiders in the 17th and 18th centuries. Today, Ita Thao, which means “I am a person,” is one of two major Thao settlements remaining, itself a result of colonial oppression as they were forced to relocate here in 1934.

Ita Thao was originally called Barawbaw by the Thao, a name that was later changed to Puji when the Japanese took over Taiwan. When the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) arrived after World War II, they named it Dehua, one of many patronizing, Chinese-centric names that were imposed on indigenous peoples during this time.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Dehua, a concept that originates with Confucius, basically means that Chinese officials behave virtuously and morally towards people (in this case Aborigines) as an example of exemplary behavior that they could follow and thus become “civilized.”

While it was the Japanese who desecrated the Thao people’s sacred island, Lalu, by almost flooding it during a damming project and renaming it Jade Island, the KMT changed it to Guanghua (光華), which means “glory to China” or “glory to Chinese.” This was changed back to its original name when the Thao were officially recognized as the country’s 10th Aboriginal community in 2001.

THE DIRTY WORD ‘HUA’

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Rungquan Lkatafatu says that even though it was the KMT who renamed their village, the term hua (化) has long been a burden on his people.

Living in close proximity to Han Chinese settlers who came in massive waves during the 18th and 19th centuries, the Qing Dynasty labeled the Thao as hua Aborigines, placing them somewhere between their shou (熟) brethren who adopted Han Chinese customs and were friendly to the government, or sheng (生), those who remained outside government control and were usually hostile. In historical records, the government defined hua as a sheng Aborigine, though one who had become “civilized.”

In 1874, the Qing Empire revoked the ban on Han Chinese entering Aboriginal areas and took these formerly “sheng” territories under their control, launching a campaign to “open the mountains and pacify the savages” (開山撫番) that devastated countless communities.

Wu Kuang-liang (吳光亮), commander of the Qing forces on Taiwan, set up the Zhengxin Academy (正心書院) on Lalu Island to jiaohua (教化), or civilize, Thao children. By this time, Thao territory had been reduced to the area around Sun Moon Lake and its surrounding foothills, and most of them were living in poverty, according to oral accounts published by the Cultural Affairs Bureau of Nantou County.

Wu also announced a set of laws to “civilize the savages” (化番俚言) that imposed Han Chinese customs of “good behavior” on them, for example, forbidding them to drink and hold feasts, requiring them to wear “proper” clothes and take on Han Chinese surnames. Each village was also asked to build a Taoist temple and worship according to Han Chinese festivals.

However, foreign diseases wreaked havoc on the Thao communities, and they eventually sold most of their ancestral land — including today’s Ita Thao — to Han Chinese settlers and isolated themselves in a number of small villages along the shore of Sun Moon Lake, where they learned to farm.

FROM COLONIZER TO COLONIZER

The Thao survivors enjoyed just a couple decades of relative stability until the Japanese colonial government began building a hydroelectric dam in Sun Moon Lake in 1919.

“Mangtu yaku kahiwan Zintun a sazum niwan tu palharutaw …” begins Kilash Lhkatafatu in his oral account, which is accompanied by a Chinese translation: “Before the water rose in Sun Moon Lake, I lived in Taringquan, a very beautiful village … there were fragrant flowers by the shore, and I could smell them in the early morning. When the devil’s pods would blossom, they smelled good too. If it was sunny in the morning, the lake would sparkle with gold.”

Before the hydroelectric plant was activated in 1934, the state-run electricity company forcefully purchased the land that would be flooded from the residents around the lake, and relocated them to higher ground. Kilash Lhkatafatu recalls that the community was offered two choices by the Japanese, but neither were appealing because the first option wouldn’t provide the community with enough firewood, and the second would relocate them close to the often unfriendly Bunun people.

Since the Han Chinese living in today’s Ita Thao area had been evacuated as well, the Japanese suggested that the Thao return there since it wouldn’t be flooded, and allowed them to use a swath of farmable land owned by the electricity company. The Thao accepted. The Japanese forbade Han Chinese to enter the area, and the remnants of Thao culture escaped assimilation.

However, things changed again when the KMT arrived. The official Sun Moon Lake government Web site describes the interactions as mostly positive, calling it then-president Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) favorite place to visit, where he brought many foreign dignitaries to relax and enjoy Thao music and dances. In 1949 he befriended Mao Hsin-hsiao (毛信孝), a young Thao man, and after being impressed by a Thao dance performance, sent a group to China to entertain the troops fighting the Communists.

Although Mao was not a chief, he became popular among KMT officials visiting the area, and according to the Web site he was able to use his influence to obtain land for his people to grow forests as well as to ask the government for electricity and permission to construct today’s Dehua Elementary School.

However, oral accounts tell a different story: since the Thao were living and farming on Japanese government land, it all became the property of the KMT after the Japanese defeat. Instead of allowing them to continue using the area, the state-run Taipower Co rented the land to the Thao. The Thao found this unfair because they were allowed to use parts of the land for free to compensate for the flooding of their previous village. Later, the land was transferred to the Nantou County Government to create an Aboriginal cultural center for tourism purposes, but this was soon abandoned due to mismanagement.

Long-classified as part of the Tsou people, the Thao began their cultural reawakening around 1998, when they began to petition the government for official recognition. They survived the massive Sept. 21, 1999 and, as last week’s events show, continue to reclaim their identity to this day.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

It was just before 6am on a sunny November morning and I could hardly contain my excitement as I arrived at the wharf where I would catch the boat to one of Penghu’s most difficult-to-access islands, a trip that had been on my list for nearly a decade. Little did I know, my dream would soon be crushed. Unsure about which boat was heading to Huayu (花嶼), I found someone who appeared to be a local and asked if this was the right place to wait. “Oh, the boat to Huayu’s been canceled today,” she told me. I couldn’t believe my ears. Surely,