Aug. 13 to Aug. 19

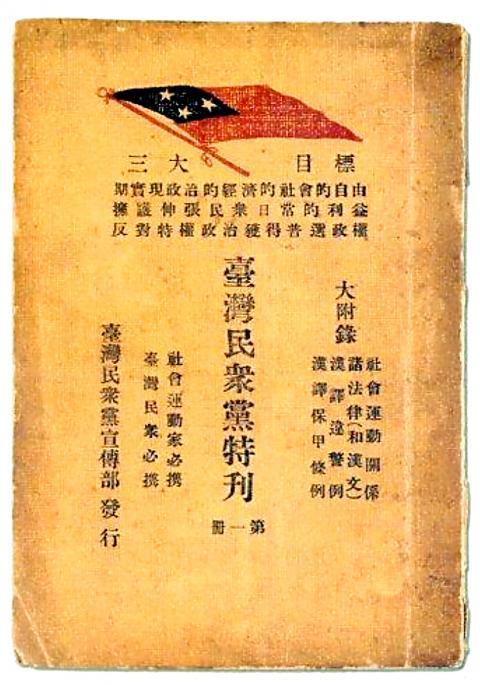

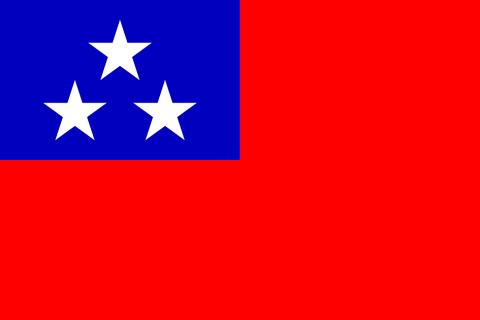

The long-simmering divide between the rightist and leftist factions of the Taiwan People’s Party (臺灣民眾黨) finally reached a breaking point. On Aug. 17, 1930, more than 200 people gathered at Taichung’s Drunken Moon Restaurant as the Taiwan Local Autonomy Alliance (台灣地方自治聯盟) was established.

Two of the party’s founding members, Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) and Tsai Pei-huo (蔡培火), were involved in the new alliance, which had the sole goal of achieving Taiwanese autonomy — whether working with anti-Japanese activists, elites who cooperated with Japan or even the Japanese themselves. They recruited Yang Chao-chia (楊肇嘉), a noted political activist living in Tokyo, to come back to Taiwan and lead the charge. Many pro-Tsai members joined as well.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The rest of the party, however, were not happy about the alliance. The central committee banned its members from joining the new group, giving the ones who had already joined two weeks to “repent” — but to no avail. On Oct. 1, the committee expelled Tsai and 16 other members, and Lin quit in protest.

This event hit the party’s leader Chiang Wei-shui (蔣渭水) hard, as it was just in its third year of existence after splitting from the Taiwan Cultural Association (台灣文化協會).

“This deeply affected Chiang’s desire to reorganize the party as a proletariat party,” writes Chien Chiung-jen (簡炯仁) in the book, Taiwan People’s Party (台灣民眾黨).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The party would not last much longer, disbanding in 1931 after mass arrests targeting Taiwanese communists, which also wiped out the Taiwan Peasant’s Union (台灣農民組合), Taiwanese Communist Party (台灣共產黨) and the New Taiwan Cultural Association (新台灣文化協會). The Taiwan Local Autonomy Alliance was the only one to survive, lasting until 1937 when it voluntarily dissolved due to rising Japanese imperialist policies.

‘MARXIST INVASION’

Chiang and Lin were longtime comrades-in-arm before they parted ways in 1930. The two first met in 1921 through the first of many petitions to the Japanese colonial government to form a Taiwan Representative Assembly, which was spearheaded by Lin.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The two soon formed the Taiwan Cultural Association, which aimed to foster a sense of Taiwanese or Han Chinese nationalism through seminars, classes, publications and other activities.

Like Chiang, Yang got his first taste of political activism through the representative assembly movement. Joining as an 18-year-old in 1924, he was one of four delegates to head to Japan to petition the Japanese Diet for the sixth time. But unlike Chiang, Yang staunchly opposed socialism, which by 1926 had taken hold in Taiwanese organizations in both Taiwan and Tokyo.

Yang describes the “Marxist invasion” as “tragic” in his memoir. Instead of working for the common good, he says, leftist ideals will lead to a class struggle that would tear apart the Taiwanese activist community as most of the officers in the Cultural Association were wealthy, highly-educated landowners.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The final showdown took place in January 1927 between the left faction, which wanted to form a political party, and the rightists, who aimed to continue cultural activities while pushing for self-rule. A Taipei City Government historical publication states that the left faction took complete control by initiating a large number of people into the association, heavily skewing the vote in their favor.

FIRST POLITICAL PARTY

Despite his later leftist leanings, Chiang left the association with Lin and the right-wing faction, eventually forming the Taiwan People’s Party in July 1927 after several attempts. It was Taiwan’s first political party, only allowed after the members vowed not to espouse Taiwanese nationalism and bar Chiang from any leadership position. This actually boosted Chiang’s reputation as it showed that the Japanese were wary of his influence.

The party tackled numerous social issues. They continued to petition the Japanese government for the assembly, pushed for self rule, freedom of speech and more educational opportunities for Taiwanese, spoke out against colonial methods of community surveillance and attempted to eradicate social ills such as opium and gambling.

Their most significant victory was alerting the League of Nations to Japan’s producing and selling of opium, earning them a visit from several officers and causing an international uproar. Although the government continued their lucrative monopoly, it did set up an addiction treatment facility.

But Chiang’s focus increasingly turned toward the working class. In 1928, he formed the League of Taiwanese Laborers (台灣工友總聯盟) and delved into the class struggle, having become a leftist by that time. This drove a wedge between Chiang and Lin, who believed that pushing for autonomy was the only way to go.

After Lin’s departure, Chiang continued on with his worker’s rights activities and also managed to force governor-general Eizo Ishizuka and three other high-ranking officials to step down by publicizing internationally the Wushe Incident (霧社事件), a violent clash between Japanese and Aborigines. The government barged into their final meeting and shut the party down in February 1931, and Chiang would die six months later.

LAST GROUP STANDING

Yang was attending college in Japan at the time, but he worked closely with Chiang. He was so aggressive in pushing the self-rule agenda that he earned the nickname “The Taiwanese Lion.” However, he watched Taiwan’s political scene descend into factionalism.

Yang shared Lin’s belief that autonomy should be the sole focus of Taiwanese activism. The rightist faction in the Taiwan People’s Party visited him on the day of his graduation, asking him to return home to join their efforts, but he declined.

In April 1930, he received a letter signed by Lin and over 10 other activists pleading for him to return and affirming that they were on the same page. He finally relented.

Five months after its inception, the alliance had swollen to more than 1,000 members, regularly drawing between 500 and 1,500 people to each of their speeches across Taiwan. The Japanese police were present at every event, often interrupting if they didn’t like what was being said.

After five years of tireless campaigning, the Japanese government finally allowed the public to elect half of Taiwan’s city and township councilors — although due to stringent restrictions only 28,000 people were eligible to run. Also, while the city councilors had partial decision making privileges, the township ones were only in a consulting role.

While Yang was unhappy with the results, he still considered it a step forward. His alliance fielded a number of candidates, all being elected but one.

The colonizers amped up their Japanization process in 1937, banning Chinese in most newspapers. In June, Lin and Yang headed to Japan to plead their case to the new cabinet one last time. Just a month later, Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China.

With Japan in full imperialist mode, the alliance met for a final time on Aug. 15, 1937, and disbanded for good.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she