July 30 to Aug. 5

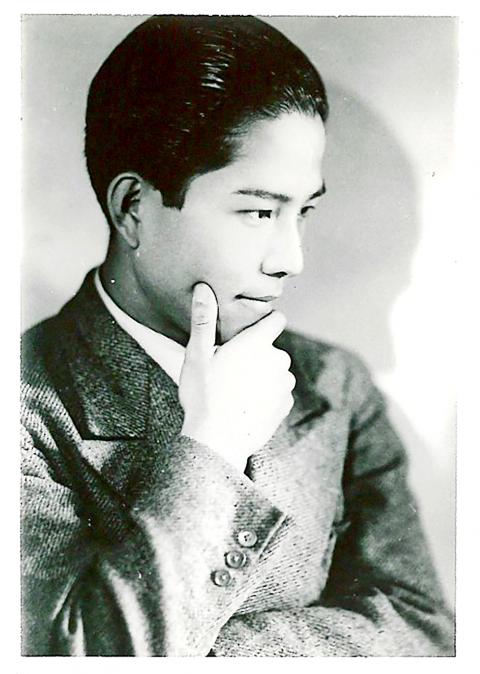

Despite his talent and accomplishments, composer Chiang Wen-ye (江文也) was a victim of circumstance throughout his life.

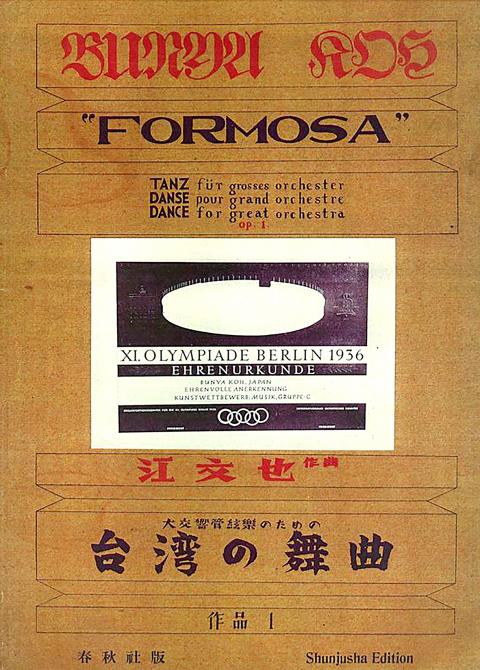

The Japanese tried to downplay his win in the 1936 Summer Olympics for Japan — Chiang, who didn’t attend the games, did not know he had won an honorable mention for his orchestral work, Formosan Dance (台灣舞曲), until a package arrived at his home nearly a month after the games concluded.

Taipei Times file photo

According to a Chiang biography by Liu Mei-lian (劉美蓮), Saburo Moroi, the only musical contestant from Japan to attend the games, failed to report Chiang’s honor when he returned home.

This was supposed to be huge news. The arts competition in the Olympics had only been around since 1912, and Chiang, along with two Japanese painters, became the first ever Asian winners that year. The next two Olympics were canceled due to World War II, and the arts competition was canceled after the 1948 games — making Chiang the only Asian to win a music medal in Olympic history.

However, the Japanese probably didn’t like the fact that the 26-year-old Chiang took the glory, while Moroi and three other experienced Japanese contestants, came up empty-handed. Chiang was young, had been learning composition for only a few years and, crucially, he wasn’t Japanese.

Photo courtesy of Liu Mei-lian

DECLARATION OF WAR

In fact, Chiang had to personally take the medal and certificate to the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun newspaper to get the word out. Other newspapers had no choice but to follow suit after seeing the report, Liu writes.

Moroi continued to publicly belittle Chiang, stating that Formosan Dance received attention solely due to its novelty factor to the Western judges as a fusion piece with strong Taiwanese and Asian elements.

Taipei Times file photo

“I believe that if we want to compete against Western pieces, we need to create works that are completely rooted in Eastern music,” Chiang told the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun. “Today’s Japanese composers are bound by their pride and ego, and aside from a few progressive ones, they find it hard to free themselves from Western theory. I have no formal musical education, so this is the only idea I can offer.”

Nevertheless, music publishers released Formosan Dance as both piano and orchestral scores, a feat that Chiang was immensely proud of, as the piece was essentially a reworking of his first composition. And in his native Taiwan, this was front page news.

“Byron once said, ‘I woke up one day and found myself famous,’” Chiang wrote in his diary, which for him summed up the year 1936.

Photo: Liu Wan-chun, Taipei Times

“I know how that feels now. My blood is boiling, my body is jumping, my life is colorful,” he wrote.

However, he was obviously stung by the Japanese critics.

“My work does have some fantastical elements in it, and this has led them to feel that it’s merely a frivolous exotic novelty and has no value. They want to ignore my existence … but this is my declaration of war to the musical world. I will continue to put myself at the perilous frontlines, but it seems that nobody treats me as a worthy opponent, only chattering about my work like a sparrow.”

SINGER TO COMPOSER

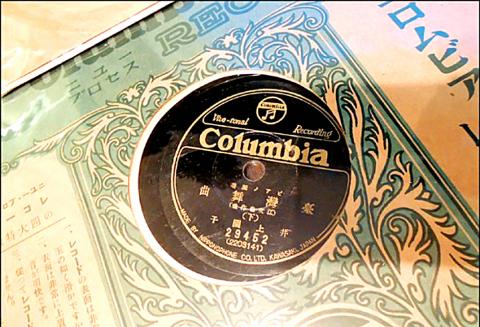

Born in 1910 in Taipei’s Dadaocheng area, Chiang actually never spent much time in Taiwan. His family moved to China’s Xiamen when he was four years old, and in 1922 he headed to Japan to study. During high school, he spent a summer interning at a power plant in Taipei. Upon college graduation, the aspiring singer auditioned for Columbia Records (the Japanese version) and released his first single, The Three Human Bomb Heroes, which commemorated three Japanese soldiers who sacrificed their lives during the invasion of Shanghai.

In April 1934, a successful Chiang headed to Taiwan for a concert tour. Lin writes that this may have been the first time a Taiwanese vocalist toured Taiwan, as previous island-wide concerts only featured Japanese singers. It was this visit that provided Chiang with the inspiration for his first composition, Nights in the City, featuring Dadaocheng, Wanhua and the center of old Taihoku around the Governor-General’s office. His desire to write about his homeland was bolstered by another tour that August with Taiwanese musicians living in Japan.

During the post-Olympics interview with the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, Chiang said: “I accidentally became a singer, but I quickly found that it was not satisfying enough for me just to sing. So I started learning composition on my own.”

Chiang continued to rack up the accolades in various competitions, and composed countless pieces, many featuring Taiwan including his four songs on Aborigines, which he referred to as “raw savages” (生蕃). In 1937, he reportedly composed the melody for the anthem of Beijing-based Provisional Government of the Republic of China, which is mostly seen today as a Japanese puppet state.

Soon, Chiang would accept a teaching job at Beijing Normal University. He split his time between Beijing and Japan, with these years being his most prolific as a composer.

DARK TIMES

When Japan surrendered in August 1945, many Taiwanese living in China were targeted by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) as former Japanese citizens. Chiang was undaunted, and even presented his latest work to the KMT, only to be arrested as a hanjian (漢奸, traitor to Han Chinese) due to his previous pro-Japanese work, which included the theme for a film about Japanese troops ravaging China.

“I forgot that life also has a side that’s dark and hypocritical,” he wrote in his diary in jail.

But this was only the beginning of the darkness. He stayed in China when the KMT retreated to Taiwan in 1949, continuing to teach and compose. But in 1957, Chiang became a prime target in the Anti-Rightist Movement which mostly targeted intellectuals. Chiang lost his job and was forced to sell his Steinway piano to make ends meet, but he continued to write music.

The final blow came in 1966, when the Cultural Revolution was in full swing. Chiang was again targeted, and ended up working as a janitor with his records, books, scores and manuscripts confiscated. He was eventually sent to a labor camp. Although he was rehabilitated and given back his professorship in 1978, Chiang’s body had suffered from years of hardship, and his glory days mostly forgotten.

Around 1980, several overseas Taiwanese musicians “rediscovered” Chiang. One of them was Chang Yi-jen (張已任), who was staying at the house of Chiang’s mentor, Russian-American composer Alexander Tcherepnin. While leafing through Tcherepnin’s collection, one composer named Bunya Koh (Chiang’s Japanese name) stood out. Chang asked Tcherepnin’s wife about the name.

“He’s Taiwanese like you,” she said.

Chang’s article on Chiang appeared in the China Times (中國時報) in 1981, and by a lucky coincidence two other Taiwanese who were researching Chiang published articles during the same month. Chiang was once again the talk of the town. But by that time he had already suffered several strokes and was a bedridden old man.

He died two years later in Beijing.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the